Visualizing The Cost And Composition Of America’s Nuclear Weapons Arsenal

The American nuclear weapons arsenal is nowhere near its 1960s peak, but, as Visual Capitalist’s Nick Routley details below, there are still thousands of warheads in the stockpile today.

The U.S. nuclear program is comprised of a complex network of facilities and weaponry, and of course the actual warheads themselves. Let’s look at the location of warheads, how they’re deployed, and the costs associated with running and refurbishing an aging nuclear program.

Let’s launch into the data.

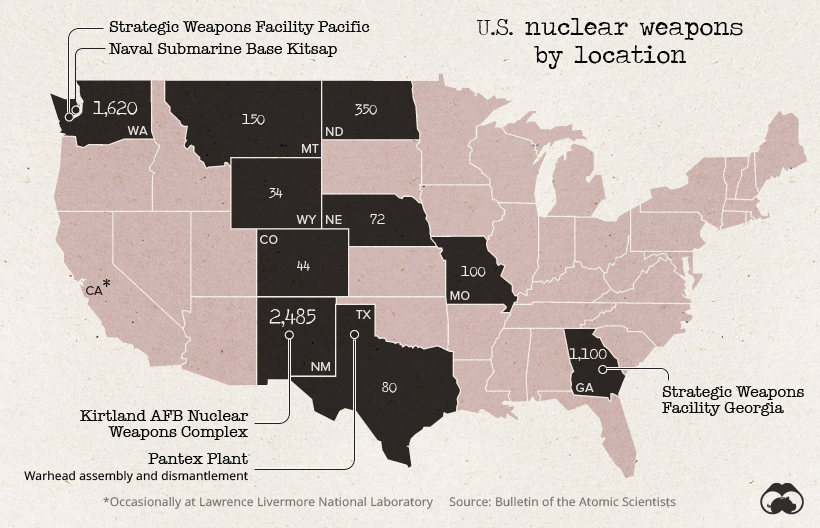

Nuclear Weapons Map

As of 2019, the U.S. Department of Defense maintained an estimated stockpile of 3,800 nuclear warheads for delivery by more than 800 ballistic missiles and aircraft. Roughly 1,300 warheads are actually deployed, while most of the remaining inventory is either held in reserve (as a hedge against “technical or geopolitical surprises”) or is destined to be dismantled.

These weapons are thought to be stored across 11 U.S. states, with the vast majority residing in New Mexico, Washington, and Georgia.

Over 1,500 of the warheads in New Mexico are retired and are destined to be dismantled at the Pantex facility in Texas.

The United States also maintains a small amount of nuclear inventory in and around Europe as well. Turkey’s Incirlik Air Base likely holds the biggest supply of warheads outside the U.S., and a few weapons are also located in storage vaults in Belgium, Italy, Germany, and the Netherlands.

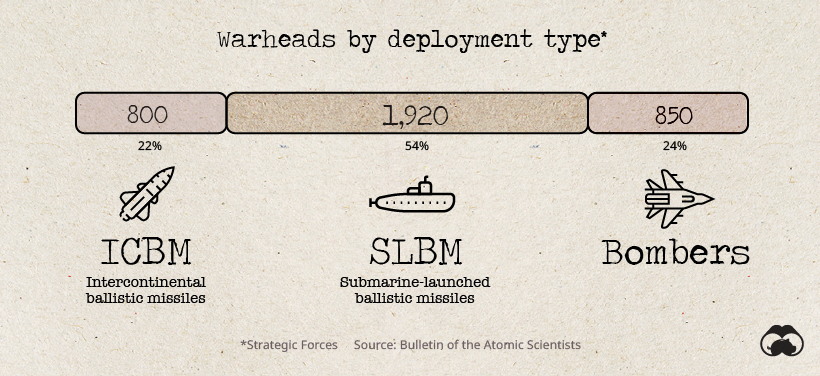

Deployment Data

Nuclear warheads, while devastatingly powerful, are nothing without a delivery mechanism. In simple terms, there are three primary methods for actually launching missiles: Silos, bombers, and submarines.

The most common deployment of nuclear weapons is under the sea. The U.S. Navy is thought to operate 14 ballistic missile submarines, with each carrying as many as 24 Trident II missiles.

Missile silos are not as popular as they once were, but the U.S. Air Force still maintains 400 silo-based missiles, and another 50 are kept “warm” in the event of an emergency.

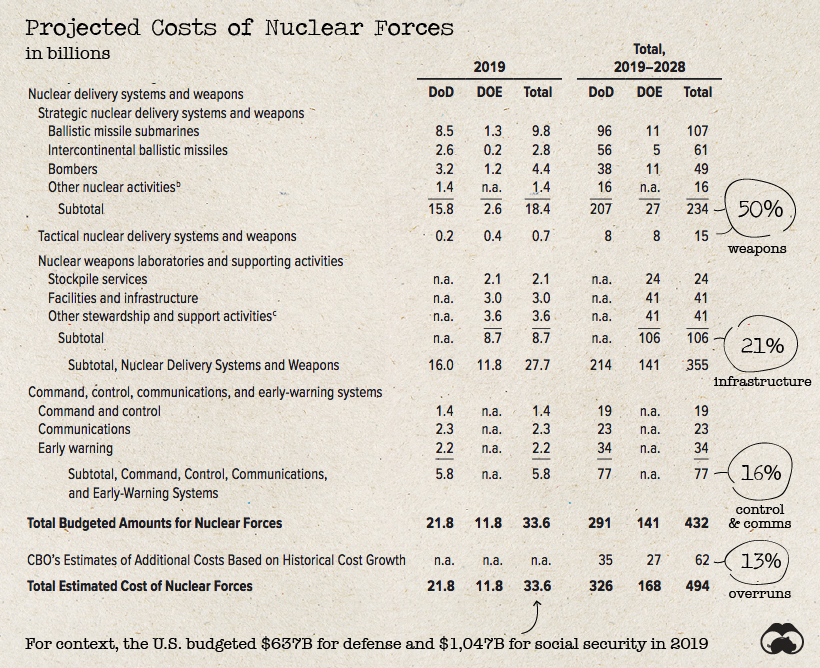

America’s Nuclear Weapons Budget

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is required to project the 10-year costs of nuclear forces every two years.

Though much of the program is shrouded in secrecy, the budget below provides an overview of the costs of running America’s nuclear weapons arsenal.

Costs in the budget are split between the Department of Energy (DoE) and the Department of Defense (DoD), which handle different parts of the process.

On one hand, the DoD takes care of the delivery systems for warheads. Those submarines, bombers, and missile silos spread around the country will add up to a projected $249 billion in costs over the next decade. Another large portion of the DoD budget accounts for operational aspects of the program, such as funding facilities, control, and early warning systems.

On the other hand, the DoE is responsible for building and maintaining the actual warheads themselves. The U.S. stopped producing new warheads in the 1990s, but all that changed last year.

Back in the Bomb Business

Generally, we think of nuclear weapons stockpiles as a sunsetting resource, slowly being dismantled; however, since the treaty that ended the arms race collapsed in mid-2019, the flood gates may be opening once again.

New warheads are reportedly rolling off the production line, and in the beginning of this year, Lockheed Martin was tapped by the U.S. Navy to manufacture low yield submarine-based nuclear missiles.

The development of lower yield nuclear weapons appears to be a response to efforts by Russia to modernize their arsenal.

Recent Russian statements […] appear to lower the threshold for Moscow’s first-use of nuclear weapons.

– Nuclear Posture Review (2018)

With this new weapons development, the U.S. is aiming to create “tailored response options” to any potential conflict. By eliminating the perceived advantages that adversaries may have, the U.S. is hoping to lower the likelihood of a nuclear conflict.

Arms control advocates warn that new lower-yield warheads entering production will lower the threshold for a nuclear conflict.

While advocates and critics of nuclear weapons debate the merits of new weapons, we appear to be entering a new era of weapons proliferation.

Tyler Durden

Sat, 02/22/2020 – 23:00