A Shift In The Global Financial Order Is Upon Us

Authored by John Authers via Bloomberg.com,

The collapse in bond yields, exacerbated by the crash in oil prices, marks an end to the era of trust in central banks…

OPEC+: A 24-Hour View

Coronavirus. That will be the first and last time this column mentions that word. Despite the weekend’s many developments in the epidemic, there is a new issue to drive the markets. Like the dreaded disease, its effect is to take an already disquieting market trend and make it far more extreme. The breakdown of the OPEC talks in Vienna on Friday, followed by Saudi Arabia’s announcement that it would abandon attempts to limit supply, and instead aim to increase market share, has driven a historic fall in the oil price.

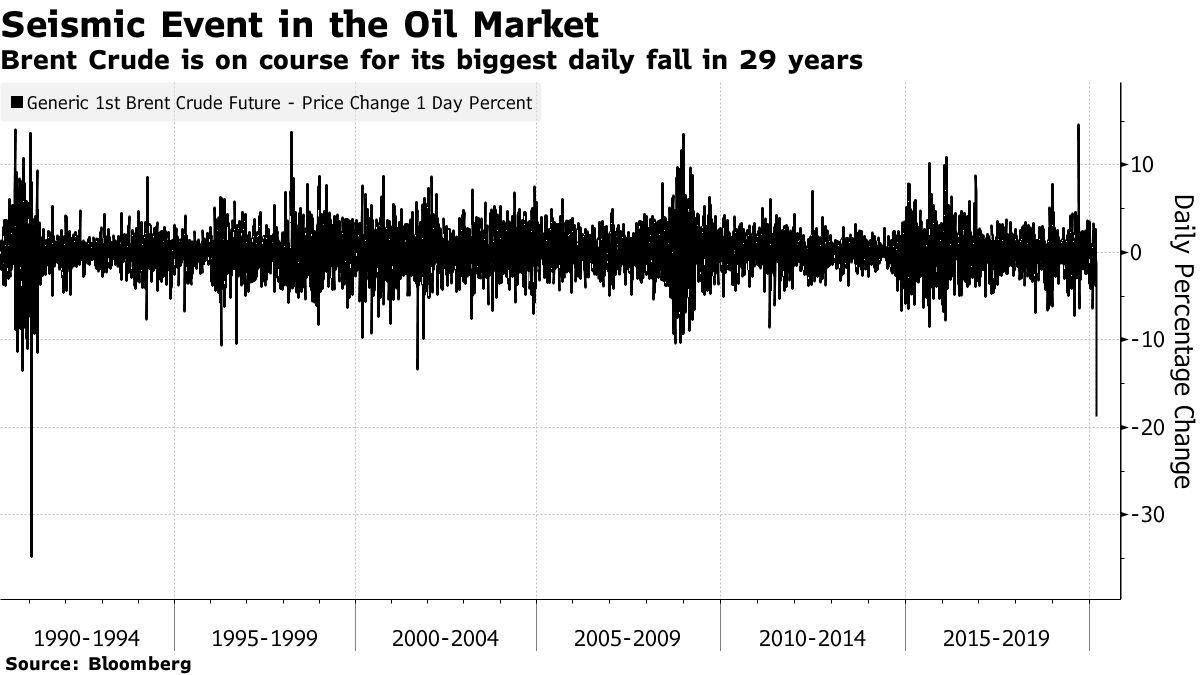

With Brent and West Texas Intermediate crude both down more than 20% when trading began in Asia, this was on course to be the worst day for the oil price since January 1991, when a coalition was fighting Iraq over its invasion of Kuwait:

Moves this dramatic can create quite a shock. This could be good news for beleaguered airlines, whose fuel will be much cheaper, and it should provide a broad economic stimulus as motorists and industrialists see fuel costs reduced. But those benefits take time to make themselves felt.

In the meantime, this will put immense pressure on anything that benefits from a high oil price. An immediate effect will be on the U.S., which has profited from the shale oil boom. The economics of that industry now come under threat — which is precisely the purpose of allowing prices to drop so far. Shale operators tend to be heavily leveraged and so now face a great risk of bankruptcy, which will hurt banks, and credit investors. That puts pressure on the Federal Reserve to cut rates further. The market now predicts the Fed will have to cut another 75 basis points off the overnight fed funds rate at its meeting this month.

Thus the virtual collapse of OPEC has led to a further collapse in U.S. interest rates. This is what has happened to the 10-year Treasury yield since the emergency cut of 50 basis points announced last Tuesday:

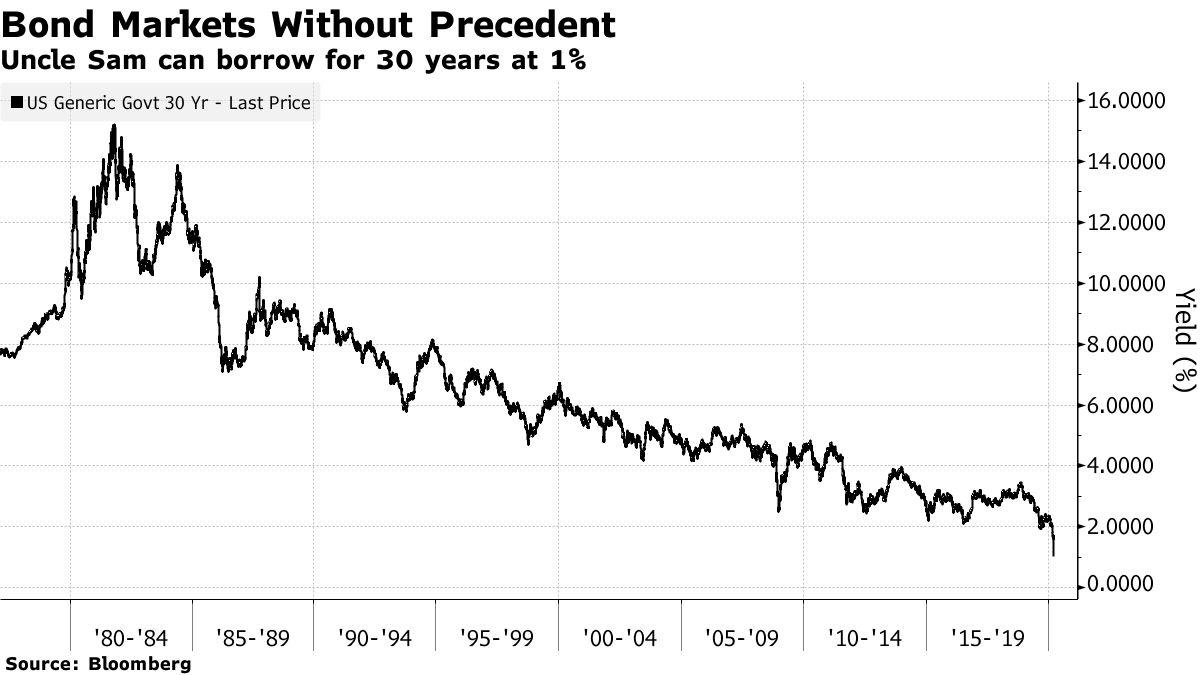

If the epidemic and the Fed’s response to it brought 10-year yields below 1% for the first time, dissension among oil producers has brought them below 0.5% less than a week later. Possibly even more remarkable is the fall in the 30-year yield, which dropped below 1% at the Asian opening, easily its lowest ever:

Central banks want to show they can raise inflation. This sudden fall in fuel costs makes that far harder, at a point when the response to the emergency cut showed that the market was already losing confidence in their ability to do so. The result has been a sharp convergence of U.S. and euro zone yields, to the narrowest in six years:

Normally when people are scared, they seek sanctuary in dollars. This is particularly true when oil falls; the dollar tends to be inversely correlated with oil, and shot up during the last major leg down for crude in late 2014. That isn’t happening this time, at least so far. The dollar has fallen to its lowest versus the Japanese yen since 2016, while gold has topped $1,700 per ounce for the first time in 12 years.

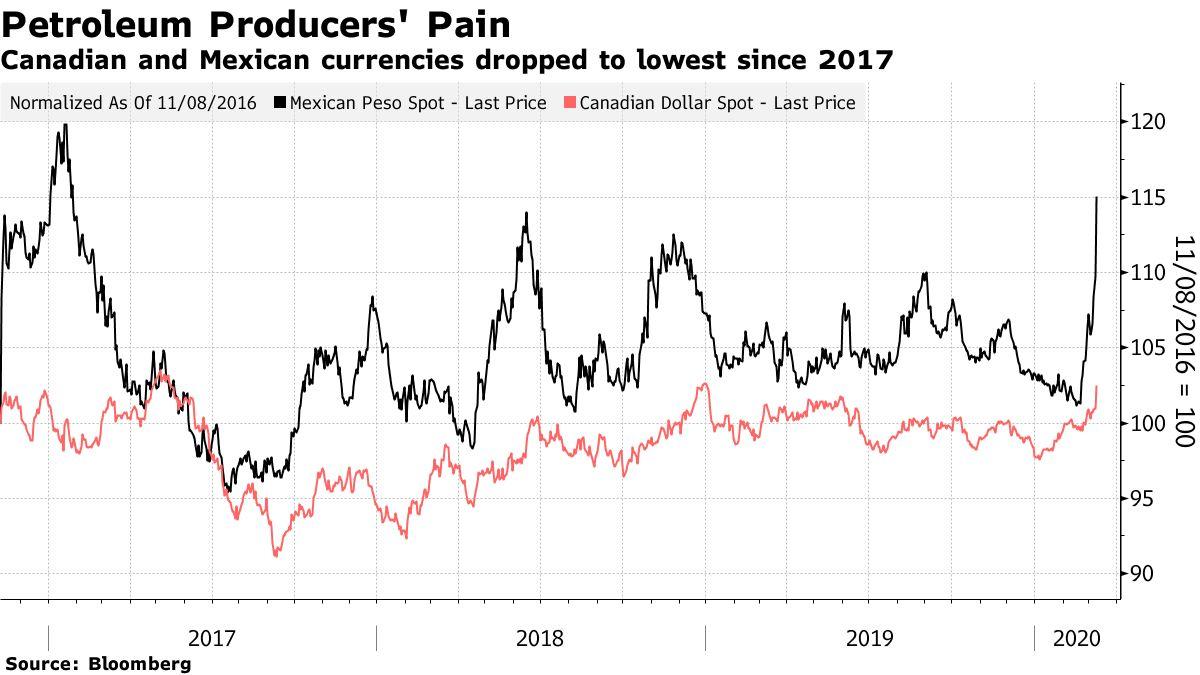

The dollar can at least enjoy some strength against petro-currencies, which benefit from higher oil prices. It strengthened sharply against the Mexican peso and Canadian dollar in Asian trading.

In the long term, there is an opportunity for everyone to benefit from cheaper fuel prices. Historically low bond yields are also effectively an invitation from the market for governments to borrow as much as they like, so if ever there was a time for fiscal expansion, this is it.

In the short term, we should expect a run on bank stocks, and energy stocks. Faced with such evidence of deflation, cyclical stocks will come under pressure. So will everything in what might be called the emerging market complex — industrial metals, as well as emerging market stocks, debt (which if denominated in dollars will be much harder to pay off), and currencies.

The Oil Standard: A 50-Year View

Having said all that, looking too closely at the drama following the OPEC breakdown might miss the point. This looks like a truly historic juncture, of the kind that comes along only every few decades, as the international financial order shifts.

After the war, the developed world was governed by the Bretton Woods accords, which tied all currencies to the dollar, which was in turn pegged to gold. It was a looser form of a gold standard, and survived until 1971. That was when Richard Nixon ended the gold peg, realizing that it had become too great a burden for the U.S., and stood in the way of the expansionary fiscal policy he was hoping to adopt ahead of his re-election campaign.

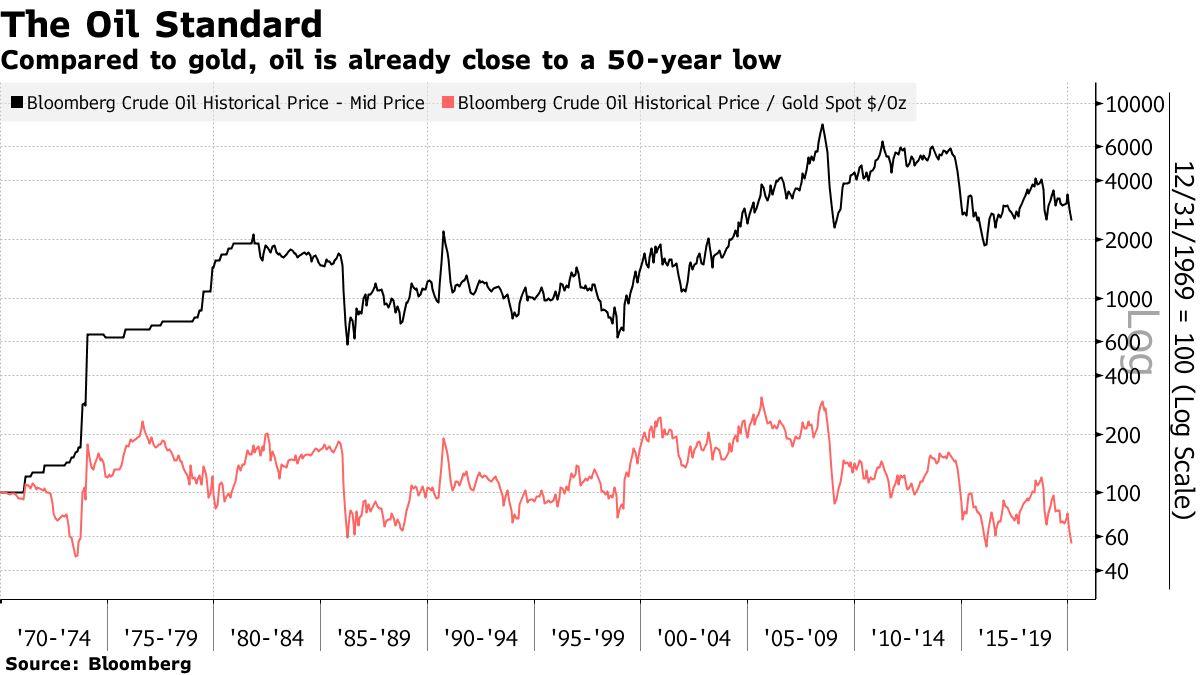

The result was a huge shock to the world order. With the gold peg gone, the financial system adopted a new anchor, which was oil. In a book published 10 years ago, I tried describing the system that replaced Bretton Woods as an Oil Standard.

Effectively, producers tried to defend themselves against the declining buying power of the dollar by hiking prices, so as to keep the price of oil in gold terms effectively constant.

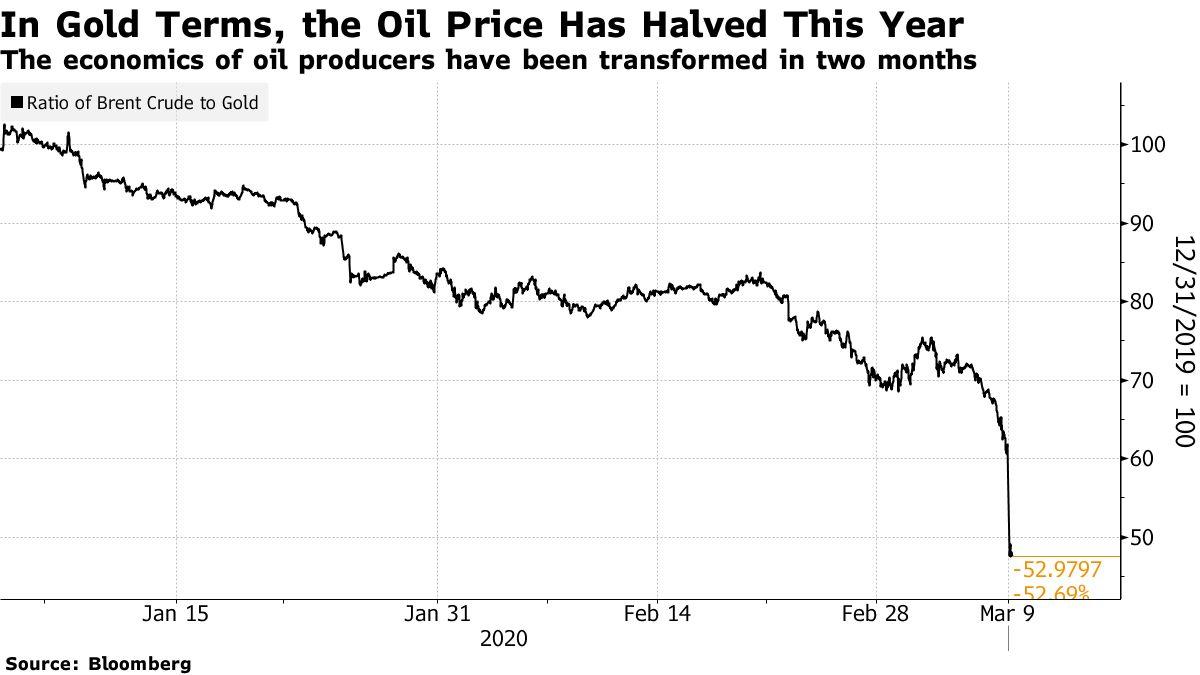

The oil/gold ratio measures how much gold you would need to pay to buy a certain amount of oil. As the chart shows, it ended the 1970s almost exactly where it had started, despite the massive increase in dollar terms.

The chart uses Bloomberg’s historic oil prices, which appear monthly, and pre-dates the latest market drama. Once updated, it will show the oil/gold ratio reached an all-time low, having already halved this year:

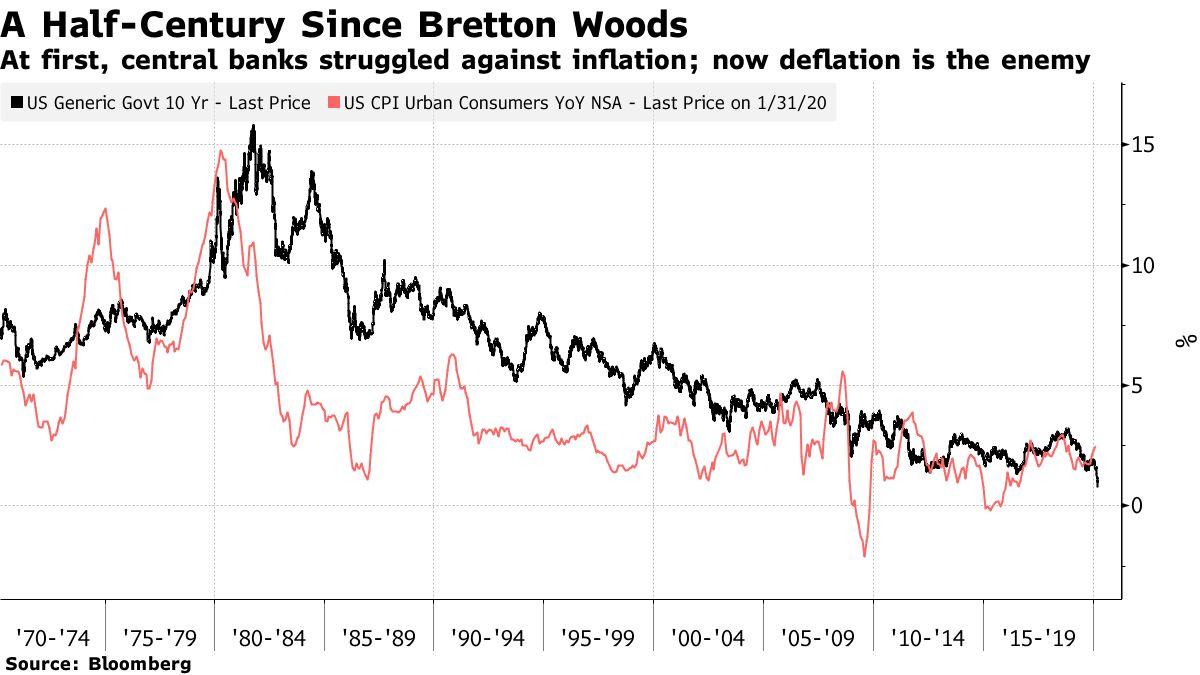

The Oil Standard era ended in the early 1980s. Markets — and everyone else — had lost faith in the ability of central banks to control inflation. Paul Volcker arrived at the Fed, raised rates more than anyone thought he would dare, provoked a recession, and convinced everyone that central banks could control inflation after all. In conjunction with the Reagan/Thatcher approach to economic management, and then the collapse of the Soviet Union and the resurgence of China, that ushered in a quarter-century of triumphalism for a new model anchored by broadly trusted central banks.

That foundered in the financial crisis of 2007-09. Now we have reached a new juncture, where the fear is that central banks cannot control deflation. For the post-crisis decade, the U.S. has managed to stay distinct, thanks in part to the privilege of the world’s reserve currency, and in part to the superior success of its corporate sector. It has done this even as Japan and Western Europe have sunk into negative interest rates, while the emerging markets have stagnated. The twin shocks of the epidemic and the oil price now appear to have wounded confidence that the U.S. can stand alone.

It certainly looks as though the world has at last arrived at a point that it appeared to have reached a decade ago. Some new financial order, to replace Bretton Woods and the system that Volcker built to replace it, is now needed. A decade of monetary expansion has delayed the issue. It is hard to see how it can be delayed much further. It would be wise to brace for disruption to match what was experienced at the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 03/09/2020 – 17:25