The Fight Against COVID-19: “Bending The Curve” & Then What?

Eradicate the virus – without a vaccine? Manage infection rates to let the population “build immunity through suffering” until a vaccine is available? How can we revive the economy without risking thousands of deaths in fresh outbreaks?

I think we’re now at the turning point in the fight against COVID-19. Everyone’s now acting to stop the spread, and the early hot spots in Europe, North America, and Australia are seeing signs of progress, just as the Asian nations did earlier. There is a long road ahead, and we have to decide which route to take, but Western societies are showing they can handle this too. In this post I’m going to show updated versions of my three favorite graphs, which tell the story and lead to the single biggest public policy-making challenge many nations may face this decade.

Bending the Curve in California: Just-in-Time Deliverance?

The graph below shows confirmed cases in Los Angeles, the San Francisco Bay Area, and California as a whole, with South Korea and Italy as contrasting examples. The vertical axis is a log scale, so exponential growth shows up as a straight line. Data sourced from the Johns Hopkins database and the California state and individual county reports.

Los Angeles lost to the Bay Area on April 2 and became California’s new COVID-19 hot spot. Shelter in place has begun working for the Bay Area, but confirmed cases have still doubled in the past week. So on March 31, our local public health officials released what I call “Shelter-in-Place 2.0,” a tighter set of rules, to try to avoid the hospital-overload scenario which hit Wuhan, Milan, Madrid, and now New York. Face masks are also becoming trendy outside the home! Will the Bay Area get a “just-in-time deliverance”, or is the worst still yet to come?

Locally, Santa Clara County – the heart of Silicon Valley – reports 30% of ICU space in use by COVID patients, 38% used by other patients, and 32% available. So they can take a doubling in COVID ICU cases without overloading, and other Bay Area hospitals have headroom too.

I used this info to estimate a Bay Area ICU limit on the graph, but I must caution that there’s not a direct relationship between “confirmed cases” and “ICU cases,” so it’s only an estimate. An outbreak in a major nursing home, or a worsening of cases-in-progress without improvement in current ICU cases, could lead to a surge in ICU demand.

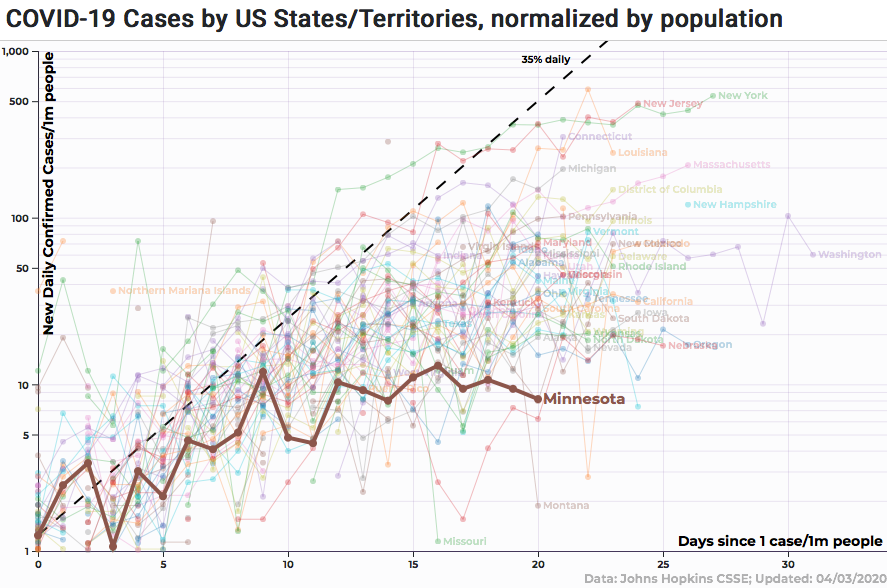

Best in the US – Minnesota Holds the Line:

The next graph takes a fresh look at the US data (again from Johns Hopkins), using the 91-DIVOC.com graphing tool. Instead of confirmed cases, this graph shows daily new cases per million population, but still with a log scale.

Last week I noted “Minnesota Bends it Best,” and here we see the result — when an outbreak stalls out, it looks like the flat curve for Minnesota. And not only is it flat, but it’s the lowest sustained level in the US. There’s other good news — Washington has stabilized (albeit at a higher case rate), and even New York (top right) might be flattening out. But Connecticut, New Jersey, Louisiana, Massachusetts, and Michigan have more work to do (click on the chart to enlarge).

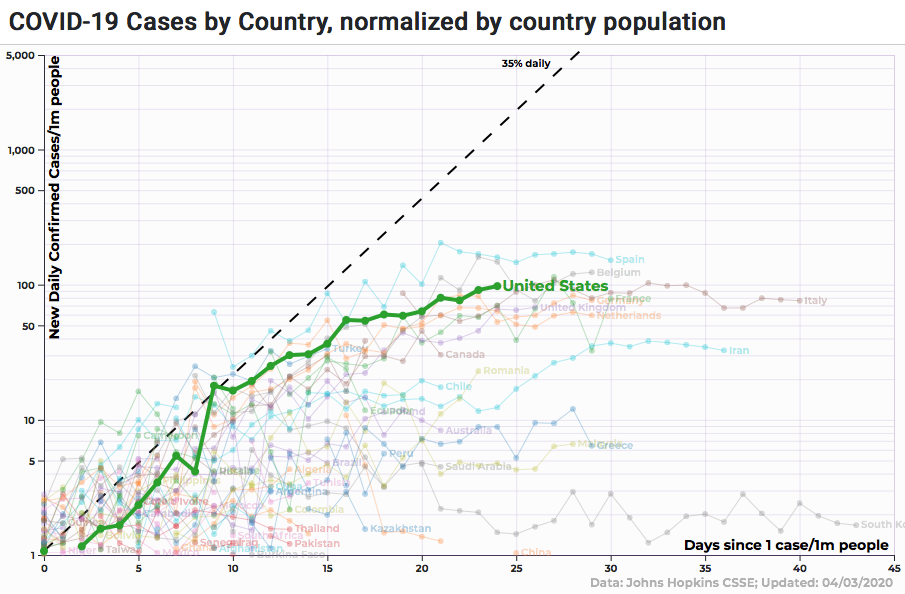

Worldwide: What Kind of Ending Can We Write?

The third graph this week shows the global situation for the 50 most populous nations, with focus on the US. Using the same tool and data as the state-by-state graph above, this one also shows daily new cases per million people on a log scale. The US is third behind Spain and now Belgium, and in the same cluster with Italy, France, Germany, the UK and the Netherlands. Growth in the US has started to slow, but it looks like we might still catch the same pain as Spain.

This graph makes it clear that most nations are at “the end of the beginning” — the daily new cases have stopped growing and are stabilizing. But other than China, no one is claiming to have driven case growth back to zero. And dissident reports from China suggest it’s in a bureaucratically-induced state of denial, not entirely in control.

So what’s the endgame here?

Do we try to eradicate the virus — without a vaccine? Do we try to manage infection rates, to let the population “build immunity through suffering” until a vaccine is available? How can we revive the economy without risking thousands of deaths in fresh outbreaks?

Some things are clear: The recovered cases can get back to normal. The infirm elderly need to be protected as much as possible. Everyone else is in between, and without a treatment or vaccine, every economic or social activity comes with some level of infection and mortality risk.

I can see two limiting-case scenarios. Both require that right now, everyone work together to suppress the virus, in every way we can. But we need to start the discussion of “what’s next” since it’s a tough policy choice, perhaps the biggest of the decade.

The first scenario, “put out the fire,” is modeled on Korea. Use shelter-in-place and face masks to suppress the growth of the virus, then use rapidly-growing testing capacity to trace and isolate the infected. With a return to “containment,” everyone else can get back to work. South Korea is doing well, and only has 100 new cases per day nationwide. But even South Korea hasn’t been able to put out the fire completely. And “get back to work” involves major changes in how work is done, to reduce infection risks every minute, every day.

The second scenario, “controlled burn,” envisions an “infection risk budget,” with a goal to keep caseloads at a level that hospitals can sustainably support, while allowing as much economic output as possible. If we risk too many infections, hospitals overflow and thousands die – reruns of New York, Milan and Wuhan. But if we can minimize the risk throughout daily life, and keep our homes safe, then that frees up room in the budget.

With that extra room, more people could get back to work and get the economy going. Even if those activities might cause a bit of spreading, it might be worth the risk (for arena sports, cruise ships and other mass social gatherings, it might not). A “controlled burn” would take a long time, but eventually everyone who needs to work will have immunity or received a vaccine, and we’ll have normal life again (provided the virus doesn’t mutate too fast). But in the absence of an effective treatment or vaccine, it will cost thousands of lives to build herd immunity this way. Is there a better way?

No matter which path is taken, policymakers will have to decide how to balance lives vs. livelihoods. And the rest of us need to learn how to prevent spread at every level, both to preserve lives and to revive jobs.

* * *

Tyler Durden

Sun, 04/05/2020 – 13:50