One Trader Started The Day With $77,000 In His Account; By The End He Owed $9 Million

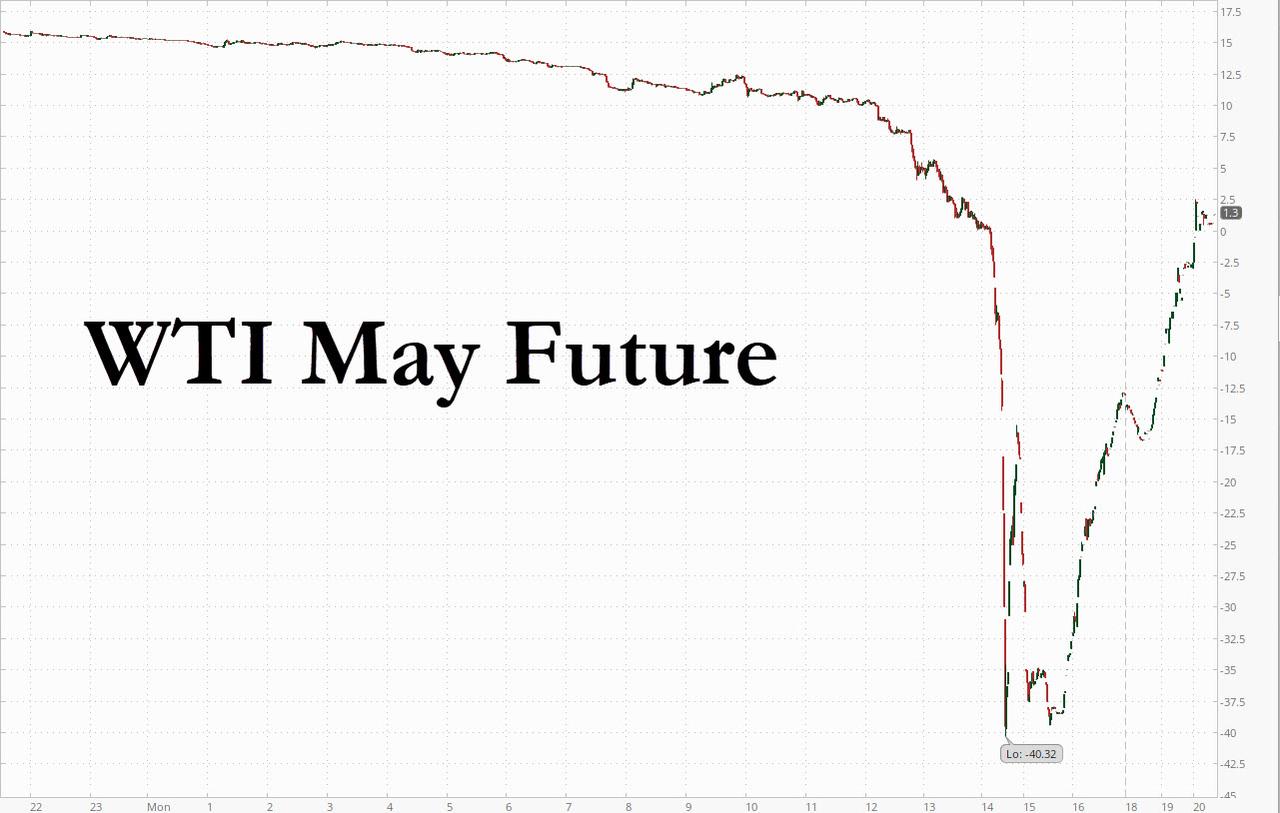

The April 20 historic oil price crash that sent the prompt May WTI contract plunging to the unheard of price of negative $40 per barrel now seems like ancient history with oil back in the $20s (at least until the June contract matures in 10 days) and stocks are delightfully levitating, but to one trader what happened on that fateful Monday will remain a permanent scar of how everything can go terribly wrong in the blink of an eye.

Syed Shah, a 30-year-old daytrader, would usually buy and sell stocks and currencies through his Interactive Brokers account, but on April 20 he couldn’t resist trying his hand at some oil trading. Shah, working from his house in a Toronto suburb, figured he couldn’t lose as he spent $2,400 snapping up crude at $3.30 a barrel, and then 50 cents. Then came what looked like the deal of a lifetime: buying 212 futures contracts on West Texas Intermediate for an astonishing penny each.

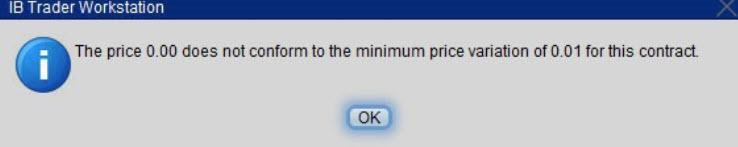

What he didn’t know, as Bloomberg’s Matthew Leising reports, is that oil’s first plunge into negative pricing had broken the Interactive Brokers platform, because its software “couldn’t cope with that pesky minus sign, even though it was always technically possible for the crude market to go upside down.”

As a result, crude was actually trading at a negative $3.70 a barrel when Shah’s screen had it at 1 cent; the reason: Interactive Brokers never displayed a subzero price to him as oil kept diving to end the day at minus $37.63 a barrel.

At midnight, Shah some very bad news: he owed Interactive Brokers $9 million. He’d started the day with $77,000 in his account, expecting that his biggest possible loss was 100%, or $77,000.

It turned out to be 116 times that number.

“I was in shock,” the 30-year-old told Bloomberg in a phone interview. “I felt like everything was going to be taken from me, all my assets.” Not that Shah had anywhere remotely close to $9 million in assets.

Shah was not alone. Countless investors, especially retail daytrades on RobinHood who had followed every tick lower in the USO by buying more of the ETF in hopes of an rebound, had a brutal day on April 20 regardless of what brokerage they had their account in.

What set Interactive Brokers apart is that its customers were flying blind, unable to see that prices had turned negative, or in other cases locked into their investments and blocked from trading. Adding insult to injury, Bloomberg reports that a big reason why Shah lost an unbelievable amount in a few hours, is that the negative numbers also blew up the model Interactive Brokers used to calculate the amount of margin – aka collateral – that customers needed to secure their accounts.

Commenting to Bloomberg, Interactive Brokers chairman and founder Thomas Peterffy, said the journey into negative territory exposed bugs in the company’s software. “It’s a $113 million mistake on our part,” the 75-year-old billionaire said in an interview Wednesday. Since then, his firm revised that loss estimate down to $109.3 million. It’s been a moving target from the start; on April 21, Interactive Brokers figured it was down $88 million from the incident.

The good news for Shah and countless others like him is that customers would be made whole, Peterffy promised. “We will rebate from our own funds to our customers who were locked in with a long position during the time the price was negative any losses they suffered below zero.”

While IB struggles to resolve the loose ends from the historic plunge, this is how Shah ended up owing millions.

The day trader in Mississauga, Canada, bought his first five contracts for $3.30 each at 1:19 p.m. on that eventful Monday. Over the next 40 minutes or so he bought 21 more, the last for 50 cents. He tried to put an order in for a negative price, but the Interactive Brokers system rejected it, so he became more convinced that it wasn’t possible for oil to go below zero. At 2:11 p.m., he placed that dream-turned-nightmare trade at a penny.

Only hours later, when he finally pulled himself from his computer, did the 30-year-old realize that oil had settled at the never-before-seen price of negative $37.63 per barrel. What did that mean for the hundreds of contracts he’d bought? He frantically tried to contact support at the firm, but no one could help him. Then that late-night statement arrived with a loss so big it was expressed with an exponent.

Across the Atlantic Ocean, Interactive Brokers customer Manfred Koller ran into a similar disaster. Koller, who lives near Frankfurt and trades from his home computer on behalf of two friends, also didn’t realize oil prices could go negative apparently failing to see the numerous warnings from CME and other exchanges that oil, would in fact, be allowed to trade negative.

He’d bought contracts for his friends on Interactive Brokers that day at $11 and between $4 and $5. Just after 2 p.m. New York time, his trading screen froze. “The price feed went black, there were no bids or offers anymore,” he told Bloomberg. Yet as far as he knew at this point, according to his Interactive Brokers account, he didn’t have anything to worry about as trading closed for the day. That piece of mind did not last long, and shortly after Interactive Brokers sent him notice that he owed $110,000. His friends were completely wiped out. “This is definitely not what you want to do, lose all your money in 20 minutes,” Koller said.

There’s more:

Besides locking up because of negative prices, a second issue concerned the amount of money Interactive Brokers required its customers to have on hand in order to trade. Known as margin, it’s a vital risk measure to ensure traders don’t lose more than they can afford. For the 212 oil contracts Shah bought for 1 cent each, the broker only required his account to have $30 of margin per contract. It was as if Interactive Brokers thought the potential loss of buying at one cent was one cent, rather than the almost unlimited downside that negative prices imply, he said.

“It seems like they didn’t know it could happen,” Shah said.

Of course, it was in fact known that it could happen and as we reported in mid-April, CME warned that benchmark oil contracts could go negative. Five days before the mayhem, the owner of the New York Mercantile Exchange, where the trading took place, sent a notice to all its clearing-member firms advising them that they could test their systems using negative prices. “Effective immediately, firms wishing to test such negative futures and/or strike prices in their systems may utilize CME’s ‘New Release’ testing environments” for crude oil, the exchange said.

And here the fingerpointing begins, because while Interactive Brokers also got that, Peterffy said he didn’t feel five days was enough time to upgrade his company’s trading platform. Five days or not, it appears that IB did nothing in anticipation of such an eventuality.

“Five days, including the weekend, with the coronavirus going on and a complex system where we have to make many changes, was not a sufficient amount of time,” he said. “The idea we could have bugs is not, in my mind, a surprise.” He also acknowledged the error in the margin model Interactive Brokers used that day.

According to Peterffy, its customers were long 563 oil contracts on Nymex, as well as 2,448 related contracts listed at another company, Intercontinental Exchange Inc. For each of those, Interactive Brokers will issue a credit of $37,630, he said.

This is where the math went haywire because according to the Interactive Brokers margin model, similar trades to what Shah placed would have required $6,930 per trade in margin if he placed them at Intercontinental Exchange. That’s 231 times the $30 Interactive Brokers charged.

“I realized after the fact the margin for those contracts is very high and these trades should never have been processed,” he said. He didn’t sleep for three nights after getting the $9 million margin call, he said.

Peterffy said there’s a problem with how exchanges design their contracts because the trading dries up as they near expiration. The May oil futures contract — the one that went negative — was expired the next day after the historic plunge, so most of the market had moved to trading the June contract.

“That’s how it’s possible for these contracts to go absolutely crazy and close at a price that has no economic justification,” Peterffy said. “The issue is whose responsibility is this?”

Well, it’s the responsibility of those who offer the contract for sale, and in this case IB had absolutely no idea what it would do when prices turned negative. And neither did the largest oil ETF, the USO, but that’s a story for another time.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 05/08/2020 – 14:55