Bubble-Wrapped Americans: How The US Became Obsessed With Physical & Emotional Safety

“In America we say if anyone gets hurt, we will ban it for everyone everywhere for all time. And before we know it, everything is banned.”

It’s a common refrain: We have bubble-wrapped the world. Americans in particular are obsessed with “safety.” The simplest way to get any law passed in America, be it a zoning law or a sweeping reform of the intelligence community, is to invoke a simple sentence: “A kid might get hurt.”

Almost no one is opposed to reasonable efforts at making the world a safer place. But the operating word here is “reasonable.” Banning lawn darts, for example, rather than just telling people that they can be dangerous when used by unsupervised children, is a perfect example of a craving for safety gone too far.

Beyond the realm of legislation, this has begun to infect our very culture. Think of things like “trigger warnings” and “safe spaces.” These are part of broader cultural trends in search of a kind of “emotional safety” – a purported right to never be disturbed or offended by anything. This is by no means confined to the sphere of academia, but is also in our popular culture, both in “extremely online” and more mainstream variants.

Why are Americans so obsessed with safety? What is the endgame of those who would bubble wrap the world, both physically and emotionally? Perhaps most importantly, what can we do to turn back the tide and reclaim our culture of self-reliance, mental toughness, and giving one another the benefit of the doubt so that we don’t “bankrupt ourselves in the vain search for absolute security,” as President Dwight D. Eisenhower warned us about?

Coddling and Splintering: The Transformation of the American Mind

Two books published in 2018 provide parallel insights into the problems presented by the safety obsession of American culture: The Splintering of the American Mind by William Egginton, focused on the tendency of Americans to tunnel themselves off into self-selected bubbles, and The Coddling of the American Mind by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt, which deals more with the tendency to avoid any uncomfortable or unpleasant information.

There is an interesting phenomenon involved in coddling: Australian psychologist Nick Haskam first coined the term “concept creep.” Basically, this means that terms are often elastic and expand past the point of meaning. Take, for example, the concept of “trauma.” This used to have a very limited meaning. However, “trauma” quickly became expanded to mean even slight physical or emotional harm or discomfort. Thus the increasing belief among the far left that words can be “violence” – not “violent,” mind you, but actual, literal violence.

In the other direction, the definition of “hero” has been expanded to mean just about anything. Every teacher, firefighter and police officer is now considered a “hero.” This isn’t to downplay or minimize the importance of these roles in our society. It’s simply to point out that “hero” just doesn’t mean what it used to 100 or even 30 years ago.

Once this expansion of a term occurs, there is never any kind of retraction. Trauma now means just about anything, and violence will soon be expanded to include lawful, peaceful speech that one disapproves of. Once this happens, there will be no going back. In the words of Sam Harris:

“We (as a society) have to be committed to defending free speech however impolitic, or unpopular, or even wrong because defending that is the only barrier to violence. That’s because the only way we can influence one another short of physical violence is through speech, through communicating ideas. The moment you say certain ideas can’t be communicated you create a circumstance where people have no alternative but to go hands on you.”

It is extremely dangerous to begin labelling everything as violence for reasons of free speech, but perhaps even more dangerous is the notion that when anything is violence, nothing is violence. Redefining words as “violence” means that we have little recourse for when actual violence occurs.

The Coddling of the American Mind notes some other concepts that are important as we speak of America’s obsession with “safety” above all else. First, that coddling combined with splintering means that people’s political views are much more like fanatical religious views than anything. They don’t see themselves as having to debate ideas or seek common ground. Rather, the opposing side and its proponents are seen as “dangerous” and must be discredited at all costs. It is worth noting that this is much more common among the left than the right or the center, which has now become more the place where “live and let live” types congregate.

The problem with this goes beyond simply being irritated by irrational people barking at you or at someone else: There is an entire generation of people who are seriously lacking in critical thinking skills. They think that labelling people and name-calling are excuses for a reasoned argument. In the words of Voltaire, “Those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities.”

These problems are hardly confined to political radicalism or academia. Indeed, the corporate sector is no stranger to this kind of safety obsession. There is the phenomenon of “woke capital,” where the corporations find the latest celebrity cause-du-jour and use it as a marketing strategy.

There is currently an extreme risk aversion in management science. Companies will now do basically anything to avoid “a kid getting hurt” or someone’s delicate sensibilities being offended.

Education from kindergarten up to the universities is increasingly about teaching doctrines and ideology, rather than critical thinking and problem solving skills. All of this is a dangerous admixture that combines the full weight of the academic, cultural and business elites in this country. And its consequences are far reaching.

Trigger Warnings and Safe Spaces

For those unaware, a “trigger warning” is a person’s advisory that disturbing content is going to be posted. However, in an example of concept creep, the meaning of “disturbing” has become expanded to mean, well, just about anything that might offend a leftist. It is also sometimes known as a “content warning,” “TW” or “CW.”

A similar concept is that of a “safe space.” What used to be a term used for a place where people in actual danger of physical harm could express themselves, a “safe space” now means a place where there is no room for disagreement or questions because language is literally violence.

This might all sound very silly and we definitely agree that it is. However, it is quickly becoming de rigeur not just in academia, which is increasingly functioning as a bizarre combination of a daycare center for 21 year olds and an indoctrination program, but also in the corporate world and in the media.

It’s not surprising that such foolishness has reached our corporate elites, because so many figures within that world come from the Ivy League. Harvard Law, for example, was the center of a controversy where they were urged not to teach rape law or even use the word “violate” (which makes it pretty hard to talk about violations of the law). A Harvard professor argued that greater anxiety among students to discuss complicated and nuanced séxual assault cases was impeding the ability of professors to adequately teach their students. This in turn would lead to poorly prepared attorneys for rape victims in the future.

Beyond a simple discussion in the academic sphere, there are student groups on campus who urge students not to attend or participate in class discussions focused on séxual violence. The same student groups advocate for warning students in advance so they can skip out on class and even to exclude “triggering” material from tests. Once again, the real victims here are the victims of séxual assault whose attorneys will be ill-prepared to advise them, to say nothing of the cumulative effect on the prosecutorial environment.

Northwestern University professor Laura Kipnis was subject to a lengthy investigation by a kangaroo court and frivolous Title IX complaints over an article she wrote for The Chronicle of Higher Education about campus séx panics. Top comedians like Chris Rock now refuse to perform on college campuses, a place that has typically been their bread and butter.

Another key term to understand here is “microaggressions” which means just about anything. Offensive statements under this umbrella include things like “I don’t see race,” “America is the land of opportunity” and “I believe the most qualified person should get the job.”

To readers of Generation X or older, this all might sound like a resurgence of political correctness and, indeed, to some extent it is. However, there is something different about the current anti-speech craze sweeping not just campuses, but also boardrooms: Political correctness was, at least in theory, about the elimination of so-called “hate speech” (for example, using “mentally disabled” instead of “retarded” or “little person” instead of “midget”) and also about broadening the canon of literature to include more women and minorities.

One doesn’t need to agree with either objective or be as generous as we are to see that the West has entered a new, accelerated and intensified version of the old political correctness that is qualitatively more dangerous. The “safe spaces” phase of this is about eliminating anything and everything that might be emotionally troubling to students on campus.

This assumes a high degree of fragility among American college students. But perhaps this assumption isn’t totally off base.

The Road to Safety Obsession

If you were born before 1985 or so, your childhood was vastly different than of those born after you. As a child, you probably came and went as you pleased, letting your parents know where you were going, who you would be with and when you might be home. You rode your bike without a helmet and if you were bullied at school there’s a good chance that you view this as a character-building experience, not one of deep emotional trauma.

So what happened?

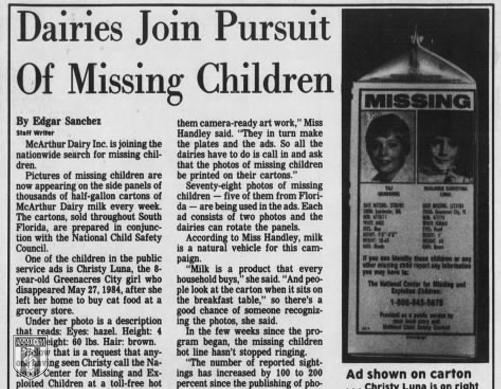

A few things. First, in 1984, the “missing child” milk carton was introduced. America became obsessed with child abduction in response to several high-profile child kidnappings over the period of a few years. Etan Platz, Adam Walsh and Johnny Gosch are just three of the names known to Americans during this time period. In September 1984, the Des Moines, Iowa-based Anderson Erickson Dairy began printing the pictures of Johnny Gosch and Eugene Martin on milk cartons. Chicago followed suit, then the entire state of California. In December 1984, a nationwide program was launched to keep the faces of abducted children front and center in the American mind.

The milk cartons didn’t find many kids, but they did create the panic of “stranger danger,” where children were taught to fear strangers even though the lion’s share of child abduction, molestation and abuse comes from friends, family and other trusted figures such as public school teachers or camp counselors. Most missing children in America are runaways and in 99 percent of all child abductions, the perpetrator is a non-custodial father. There is at least one case of “stranger danger” being harmful – a lost 11-year-old Boy Scout who thought his rescuers were looking to kidnap him.

Some of the protocols established out of this were useful, such as AMBER Alerts and Code Adam. Awareness of child abduction in general was raised and as a result there’s significantly fewer child abductions today than there were in 1980. Indeed, stranger abduction is incredibly rare in the United States. But this has come with a dark side.

You might be familiar with the myriad of cases in suburban America where children playing alone are arrested by the police because they don’t have adult supervision. The parents are then questioned by the police or, in some cases, the state’s Child Protective Services.

There was also the panic after the mass shooting at Columbine High School, which led to the bubble wrapping of schools alongside the home. “Zero tolerance” policies were implemented alongside school-wide peanut butter bans.

And so the result is that there are at least two generations of American children raised in a protective net so tight that they not only have trouble expressing themselves, but also being exposed to failure and discomfort. What began as a good-faith effort to prevent child abduction and increase overall child welfare has ended up, as a side effect, creating a world where children were raised in such safety that they can’t even handle being upset.

This has not only insulated children from the consequences of their own actions and the normal pains of growing up, but also gives the impression that no matter what their problems, “adults” are ready to step in and save the day at any moment.

It’s worth noting that, in recent years, there has been a sharp rise in mental illness among young people, both on campus and off, including those with severe mental health problems.

Cops and the 24-Hour News Cycle

There are two other cultural phenomena worth exploring: The television series Cops and the 24-hour cable news cycle. As of April 2020, Cops is still on the air, having moved from Fox to Spike TV in 2013.

Cops was more than just a TV series, it was a cultural phenomenon that changed television. The cinéma vérité style used by the show was to be copied in the 90s by virtually every reality show you can name. Curiously, it came out around the same time that crime rates had plummeted comparatively to the 70s and 80s. And just at that time, people started having the worst in human behavior beamed into their homes for entertainment every Saturday night.

At the same time, CNN was bringing news into your home 24 hours a day without end. This meant they had to fill programming around the clock – and most news is bad news. So in addition to a hugely popular program centered around chasing criminals in the act, Americans also had a constant stream of bad news and dangerous events pumped into their homes. The result was the end of the “free range child,” the kind who learned through play and discovered risk management through trial and error. This was replaced with children whose entire existence was micromanaged by adults, with little to no unsupervised play time.

The ability to learn through failure is a well-established principle going back to the Greeks, who called it pathemata mathemata (“guide your learning through pain”). The knowledge and wisdom gained through failure and pain are arguably more lasting and valuable than those learned in school.

The Generation Gap: Millennials and Gen Z

Older generations (Generation X and Baby Boomers) have a tendency to conflate Millennials and Gen Z (also known as “Zoomers”). However, there are two key differences, one cultural and one clinical: First, Zoomers are much more digital natives than their Millennial counterparts. They didn’t get constant internet access or mobile access at college. They’ve had it since they were in middle school in many cases.

While this is bound to create secondary cultural differences, we know of one clinical difference between Millennials and Zoomers: Zoomers are much more prone to mental illness, specifically depression, anxiety, alcoholism and self-harm.

Depression and anxiety in particular are through the roof for girls, with moderate increases for boys. While self-reported cases are up, we also have harder clinical data: There has been a 62 percent increase in hospital admissions.

The Baby Boomers and Gen Xers created an environment where it is safer than ever to be a child, but at what cost? There has been widespread and verifiable psychological damage done to the younger generation, which is likely being compounded by the coddling taking place in our nation’s universities.

Screen Time and Social Media

“Screen time” is the new obsession for parents, especially among, ironically, those who work in high-tech Silicon Valley jobs such as Steve Jobs, father of the iPhone. But there seems to be an emerging consensus among those who have actually studied the topic that the problem isn’t “screen time” per se, but rather the more specific use of it in the form of social media. This has been identified as the cause of depression and anxiety, particularly among girls.

Why is social media usage particularly impactful among girls? Dr. Haidt and others postulate that it’s because they are more sensitive to the “perfect” lives being lived by beautiful social media influencers – at least the lives that they lead online. What’s more, there is a lot of exclusion and bullying taking place on social media. In days past, you only heard about the party you didn’t get invited to, but now you get to watch it unfold in real time on Snapchat or other platforms. And cyberbullying is much harder to track and police than its real world equivalent.

There’s a related bubble wrapping going on with regard to a different sort of screen time: Kids today are often forbidden from playing with plastic guns or even finger guns. There is the notorious case of the 7-year-old child who was suspended for biting a Pop Tart toaster pastry into the shape of a gun. But millions of children come home (from the same schools where finger guns can warrant a suspension) to play Grand Theft Auto for hours on end.

Indeed, there is some evidence that suggests that violent movies and video games can trigger violent thoughts in some, but not all, people who view them. The National Institute of Mental Health has done an extensive study detailing the impact that violent media has on those who view it.

A Nation Divided

There’s not much hyperbole in saying that America is barely a single nation anymore. We talk about “red states” and “blue states,” but the divide is much deeper than that. Even the coastal states largely have an urban college-educated Democratic population and a rural non-college-educated Republican population.

While some animosity between different areas of the political spectrum, or even resentment of cities by the countryside and vice versa, is nothing new, the rancor took off sharply in the early 2000s following the controversial election of George W. Bush and his expanded imperial presidency after 9/11.

Social media makes it easier for extremes to amplify their anger. What’s more, it’s much easier for people to become part of an online crusade – or witch hunt – than it is for them to do so without it.

This is a big part of what is behind the string of disinvitations and protests on American college campuses. No one, especially young people (where “young” means “under 30”), can bear to listen to the opinions of someone they don’t agree with. Disinvitations aren’t limited to highly controversial figures like MILO and Richard Spencer, or even the decidedly much more vanilla Ann Coulter. Condoleeza Rice, the first black female Secretary of State, was disinvited in 2014, as was the first female head of the IMF and the first female finance minister of a G8 nation, Christine Lagarde.

Because Americans increasingly refuse even to listen to arguments from the other side, inserting instead a strawman in favor of reasoned debate, there is no reason to believe that the American political and ideological divide will not increase.

The Evolution of Victimhood Culture

America and the West have largely adopted a victimhood culture. It is worth taking a minute to trace this radical transformation of values in the West from its origins.

The earliest societies in the West were honor cultures. While it sounds like a no-brainer that we should return to an honor culture, we should unpack precisely what this means. An honor culture usually means a lot of interpersonal violence. Small slights must be dealt with through dead violence – because a gentleman cannot take any kind of stain on his honor. Dueling and blood feuds are common in these kinds of cultures.

This is superseded by dignity culture. Dignity culture is different, because people are presumed to have dignity regardless of what others think of them. In a dignity culture, people are admired because they have a “thick skin” and are able to brush off slights even if they are seriously insulting. While we might find ourselves offended, even rightfully so, it is considered important to rise above the offense and conduct ourselves with dignity. Everyone heard some variant of “sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me” growing up as a child. This is perhaps the key phrase of a dignity culture.

Victimhood culture is concerned with status in a similar manner to honor culture. Indeed, people become incredibly intolerant of any kind of perceived slight, much in the manner of an honor culture. However, in a victimhood culture, it is being offended, taking offense, and being a victim that provides one with status.

Victimhood culture means that people are divided into classes, where victims are good and oppressors are bad. There is an eternal conflict with eternal grievances that can never fully be corrected or atoned for. People feel the need to constantly walk on eggshells and censor themselves. This leads to an overall emphasis on safety, as even words become “violence” – we need trigger warnings and safe spaces to protect us.

Victimhood culture is closely associated with safety culture. Safety culture is, above all else, debilitating. Those who choose a marginalized identity – and in the contemporary West, a marginalized identity is almost always a choice – become more fragile and more dependent on the broader society. At the same time, the powerful elements in society gain a stake in reinforcing this marginalized identity. The Great Society provides a case study in this dynamic.

Those who do not receive the so-called “benefits” of safety culture are frequently more prepared for the real world. Who would you rather hire? Someone who studied hard in a rigorous discipline for four years or someone who spent four years being coddled in what is basically a day care center for twentysomethings? With this in mind, it’s not too big of a leap to see that straight white men might actually have become “privileged” through the process of not having access to the collective hugbox in higher education.

The Role of Lawyers and Litigation

There is a relationship with the litigious society in which we live with warning labels everywhere, often for hazards that would seem incredibly obvious to most observant people. In previous generations, even power tools didn’t come with warnings to roll your sleeves up or take off your watch. This information was either common sense or passed along in high school shop classes or on the job.

However, the American legal system has no penalty for frivolous lawsuits, which has led to an explosion in the number of lawsuits. There is a massive army of lawyers in the United States (which has a surplus of some 40 percent) whose profession revolves around finding aggrieved parties who weren’t properly “warned” – or indeed to be able to help write the warning labels themselves. These labels do not even exist for actual safety. The same type of person who is going to do the thing being warned against is likely the same type of person who doesn’t read warnings. The labels are simply there as a form of “CYA” for the firms who make them.

That said, to a certain degree, the “litigious society” is a myth. The oft-cited McDonald’s coffee burn is actually more reasonable than people are aware: The elderly woman in question who was burned simply wanted McDonald’s – who kept their coffee extra hot to prevent people from taking part of their “free refills” policy – to pay for her skin graft resulting from the burn. When McDonald’s refused to settle this out of court and the case went to trial, they were rewarded for their efforts at stonewalling with punitive damages.

So the main example of frivolous lawsuits is a big strawman. But to be clear – frivolous lawsuits are real. One great example of an actually frivolous lawsuit was the man who sued his dry cleaner for $67 million because they delivered his pants to the wrong person. There was no actual damage here and it’s difficult to express just how ridiculous the dollar figure claimed was. This case was thrown out of court, as most of these types of cases are. Still, litigants pursue them either to get media attention or to harass the defendant or both, a phenomenon known as “lawfare.” And these cases clog up genuine claims in the courts.

Civil trials are long and drawn-out things. And with 40 million of them in the United States every year and over a million lawyers, it’s unsurprising that the system has become clogged with lawsuits, many of which are either totally frivolous (remember – there’s no penalty for filing a frivolous lawsuit in America) or just the type of thing that should be either settled or handled through binding arbitration.

While the litigious society exists in parallel to the “safe spaces” of college campuses, it is worth noting because it is part of the larger bubble wrapping of the American landscape. The same kids who were raised with helicopter parents and a general sense that they had a “right” to never be offended were likewise raised in an environment where people could be sued for anything or, at the very least, this was the public perception. It is just another factor of risk aversion in American life.

There are other consequences of having too many lawyers around and having them congregate within our political class: Words are chosen to obfuscate and laws proliferate, as legislation becomes a sort of “jobs program” for lawyers. The more laws we have, the less free we are and the less social trust we have. As laws, regulations, and agencies take the place of civil society, the state grows at the expense of everything else and the less trust we have in our society.

Overreacting to the Wuhan Coronavirus

In 2020, the Wuhan Coronavirus broke out of China and spread all around the world. The world had not seen a deadly, contagious virus with such scope since the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 to 1920. At first, the response was denial and apathy. However, this quickly gave way to what could be considered a massive overreaction: Shutting everything down.

There was a certain logic to this: If people gathering together were what was spreading the virus, then simply keep people apart until the whole thing blows over. However, this is also potentially a huge overreaction. It is a medical solution in the driver’s seat without any nod to the economic, social or military consequences that flow from it. Even if one agrees that medical solutions are to be the primary driver, it does not follow that they are the only driver.

Because of the lopsided and often hysterical reaction, many of the proposed solutions don’t even make sense: For example, telling everyone they can go to the supermarket while prohibiting them from going to small offices, or shutting down the border between the United States and Canada – two countries with highly infected populations and a sprawling border that is largely unpatrolled.

A brief disclaimer: None of us are epidemiologists or virologists. And we defer to their superior knowledge on this subject.

However, during the Spanish flu pandemic, life did not shut down quite so completely as it has during the Coronavirus pandemic. The methods used during the Spanish flu were isolation of the sick, mask wearing in public, and cancellation of large events. In places where these were practiced rigorously, there was a significant decline in the number of infections and death. St. Louis in particular is known as an exemplar of what to do during an easily transmissible epidemic.

“The economy” has been cited as a reason the total shutdown of life during the Coronavirus pandemic was a poor idea. This might sound frivolous, but the mass unemployment not only leads to destitution for those when the economy is so paralyzed that there are no other jobs forthcoming. It also leads to a spike in the suicide rate. There is a certain calculus that must be done – how much unemployment is worth how much death from Wuhan Coronavirus?

The reaction to this virus is noteworthy, because it is the first major pandemic of this new, insulated and coddled age. Rather than reasonable measures to mitigate death, the choice made was to do anything and everything possible to prevent death entirely. Not only might this be an unwise decision, it might be a fool’s errand: The virus seems to be much more contagious than was previously thought, as well as much less lethal.

More than one reasonable person has asked what would happen if we all just went about our lives making reasonable precautions, such as hand washing, mask wearing, social distancing, and the cancellation of large events like sports and concerts. This is effectively what Sweden has done and it appears to work, especially when contrasted with their neighbors in Finland who have done basically the same as America. How much sense does it make to have the entire community converge upon its grocery stores while not allowing anyone to go into an office, ever? Compare this with what has passed for reasonable reaction: Closing down every school, every dine-in restaurant, and the government dictating which businesses are essential and which aren’t.

A big motivator of this is a compulsion to not lose a single life to the Wuhan Coronavirus, which is a totally unreasonable goal. People are going to die. The question isn’t “how tightly do we have to lock the country down to ensure no one dies,” but rather “what are reasonable measures we can take to balance public safety against personal choice and social cohesion?”

The splintering and division of America in practice has meant that the establishment conservative media was largely in denial over the virus for weeks. It is not a liberal smear to say that the amount of denialism from establishment conservative media, pundits, think tanks, bureaucrats and elected officials has in practice meant that America responded much more slowly and conservatively than it might have with a more unified America body politic.

At the beginning of spring 2020, the virus seemed poised to devastate the American South, which largely stuck with the early conservative media denialism, eschewing social distancing, shuttering of certain public places and mask wearing. Again, a more united body politic and the media and trust in the media that goes along with that might have prevented a lot of illness and death.

Imagine the impact of Walter Cronkite or Edward Murrow going on television and telling the American public to mask up and maintain distance versus the impact of Rachel Maddow and Tucker Carlson doing it.

What Is Vindictive Protectiveness?

“Vindictive protectiveness” was a term coined by Haidt and Lukianoff to describe the environment on America’s college campuses with regard to speech codes and similar. However, it can refer more broadly to the cultural atmosphere in the United States and the West today. From the college campus to the corporate boardroom to the office, Americans have to watch what they say and maybe even what they think lest they fall afoul of extra-legal speech and thought codes.

Perhaps worst of all, an entire generation is being raised to see this not only as normal, but as beneficial. This means that as this generation comes of age and grows into leadership positions, that there is a significant chance that these codes will be enforced more rigorously, not less. And while there may be ebbs and flows (political correctness went into hibernation for pretty much the entire administration of George W. Bush – though to be fair, there was an imperfect replacement in the form of post-9/11 jingoism), the current outrage factory is much more concerning than the one that sort of just hung around in the background in the 1990s.

Put plainly: the next wave will be worse. We may not have Maoist-style Red Guards in America quite yet, but we’re not far off and the emphasis should be on “yet.”

Tyler Durden

Sat, 05/09/2020 – 22:20