“We’re All Government-Sponsored Enterprises Now…”

Authored by Scott Minerd, Global CIO, Guggenheim Investments,

Eight weeks have passed since the Federal Open Market Committee held an extraordinary Sunday meeting and cut the fed funds rate to zero. Since then the Federal Reserve (Fed) and Congress have unleashed vast fiscal and monetary resources to support the economy and financial markets. I have my opinions on the efficacy and long-term consequences of those policies, but as an investor, I do not have the luxury of moralizing. My job is to understand how markets function, assess value in whatever conditions we find ourselves, and position client portfolios accordingly.

Our portfolios reflect the view that we are likely going to be facing a long period of repression in the yield curve, and that the risk of significant widening in high-quality credit spreads has been reduced by the market’s faith in the Fed’s new facilities. As a result, we believe our conservative positioning before the crisis has positioned us well to aggressively take advantage of market dislocations and opportunistically add credit exposure.

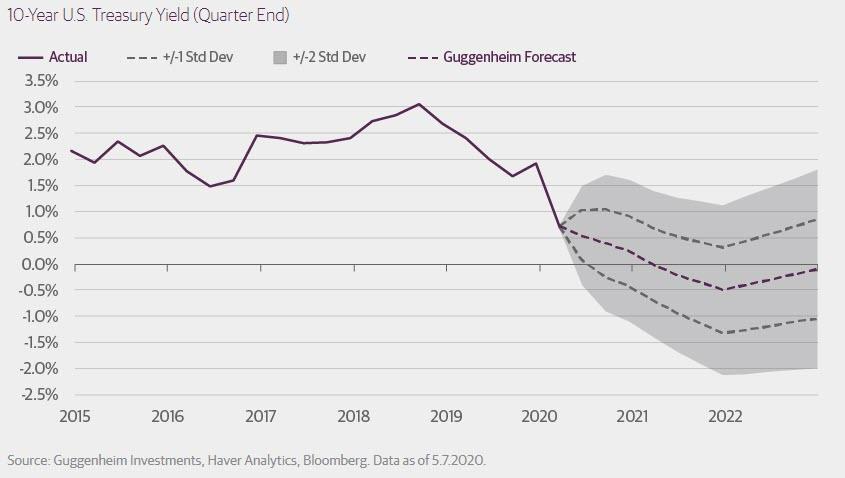

Interest rates are not likely to skyrocket anytime soon despite massive Treasury issuance. Given the economy’s and U.S. Treasury’s need for continued support by the Fed, utilizing bond buying and forward rate guidance will, over time, continue to exert downward pressure on rates. I see the yield on the 10-year Treasury note falling to 25 basis points or lower very soon, with a possibility that it will go negative in the intermediate term—our target is -50 basis points, and in certain circumstances it could go meaningfully lower. The long bond could ultimately reach around 25 basis points as the 10-year and 30-year area of the curve shifts down by over 100 basis points from where it is today.

Treasury Yields Are Heading Even Lower From Here

The Fed’s and Treasury’s expanded support for credit markets and corporate borrowers has significantly reduced tail risks in pricing. Liquidity provided by the Fed will keep prices in check for a wide range of securities. It has also removed some of the hazards that lead to default, such as being shut out of the market when in need of money. Prior to the March 23 announcement of the Primary and Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facilities (PMCCF and SMCCF), it was unclear if companies like Boeing would be able to raise money in primary credit markets at any affordable level. But on April 30, Boeing raised $25 billion on a deal that was met with $70 billion in orders, making it the sixth largest corporate bond placement on record. In fact, investment-grade corporate bond issuance this year has broken the previous monthly record twice, with March volume of $262 billion breaking the previous record in May 2016 of $168 billion, and April volume of $285 billion breaking March’s record. Year-to-date investment-grade bond issuance through April totals $765 billion, putting 2020 on track to easily surpass last year’s total of $1.1 trillion.

Many companies, including Boeing, Southwest, and Hyatt Hotels, have likely gained access to financing simply on the strength of the government’s intentions to intervene in credit markets. Successful debt offerings have also been completed by recent fallen angels like Ford and Kraft Heinz, both of which had corporate bonds trading at or near distressed levels only weeks ago. This was a real success for corporate bond issuers, but it was also a success for the Fed.

The Fed has yet to buy a single bond in the SMCCF, but the mere announcement of the program has managed to tighten credit spreads dramatically and greatly ease liquidity issues. This reminds me of the period between 1942 and 1951, a period in which the Fed targeted a maximum rate of 2.5 percent on long-term Treasury bonds. Amazingly, the Fed ended up buying only a small amount of Treasury debt during that period. The reason, of course, is that the market perceived that the Fed had given Treasury investors a put. Any time rates began to approach 2.5 percent, investors would step in and start buying because there was very little downside. A similar dynamic is at work right now in the credit markets.

The support on offer to corporate America during this period of economic shutdown risks the creation of a new moral obligation for the U.S. government to keep markets functioning and help companies access credit.

This means that corporate borrowers are most likely on the way to becoming something akin to government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The difference is that in this cycle, it is not a specific institution that is too big to fail, it is the investment-grade bond market that is too big to fail.

Before the financial crisis of 2007-08, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac operated with the implied backing of the U.S. government, and the senior securities they issued—mortgage-backed securities and Agency debentures—were referred to as moral obligations of the U.S. government. There was no legal requirement for the U.S. Treasury to pay off or guarantee their senior securities, but during the extreme conditions of the financial crisis, when liquidity dried up for the Agencies’ securities and their capital position deteriorated, the Treasury stepped in. The Fed played its part, with the first de facto quantitative easing (QE) program taking the form of outright purchases of Agency discount notes and, ultimately, the U.S. Treasury offered its unconditional guarantee on Agency mortgages and debentures, which ended in conservatorship. The implicit support that the markets and rating agencies had relied upon for years to justify their pricing and low capital charges turned out to be correct. Fannie and Freddie actually were an obligation of the U.S. government, and the government made good on it.

Rating agencies and regulators had long assigned value to the implicit government support that led to similar treatment for Agency debt as that of U.S. Treasury obligations. If the rating agencies believe that these pandemic programs are going to reduce default risk then it logically follows they will be slower to downgrade companies (or may, under certain circumstances, consider upgrading them). That does not mean every company is going to get bailed out, or that every bad credit will be turned into a good credit, but at the margin some questionable credits will not only have lower risk of default, but they will also have lower risk of downgrade and pay lower rates of interest.

What could go wrong with my outlook?

We are already in uncharted territory and another black swan might emerge in the midst of a very fragile market. Or a second-order event could create irreversible damage such as large default volumes in the emerging markets. Risks from reopening the economy are two-sided: State and local governments could ease up on lockdown restrictions, the spread of the virus could prove to be manageable, and the economy could come roaring back—unlike what we’ve predicted, which is more of a checkmark-shaped recovery than a V-shaped recovery. On the other hand, the easing of restrictions could lead to a second spike in the coronavirus that is even worse than what we have already lived through, leading to a new leg down for the economy and markets.

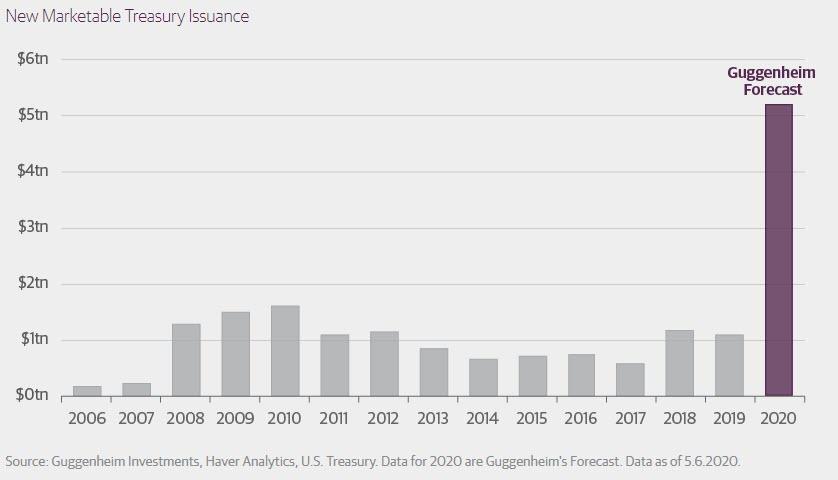

Another risk is the Treasury itself. The Fed will need to conduct another $2 trillion of QE this year to keep the Treasury market functioning given the size of the deficit. Net coupon issuance for the rest of 2020 will approach $1.5 trillion, and net bill issuance could add another $2 trillion. There is just not enough available credit in the world to absorb all of these Treasury securities without crowding out other borrowers. If at some point markets begin to question the efficacy of QE, or the Federal Reserve is perceived to be behind the curve in making necessary asset purchases, we could very well get a tantrum in the Treasury market, which would likely spill over into a tantrum in corporate credit, and into the stock market.

Treasury Issuance Will Shatter Records in 2020

Any of these risks could affect my outlook. But as Americans we will need to have more faith in the willingness and the ability of our government to print money as the ultimate solution to every problem. In extreme conditions, the real function of central banks is to print money when necessary to make sure the government gets financed. This is the dirty little secret of central banking. Central bankers won’t openly admit to this, but we have seen this reaction function time and time again, and in every cycle it only gets bigger.

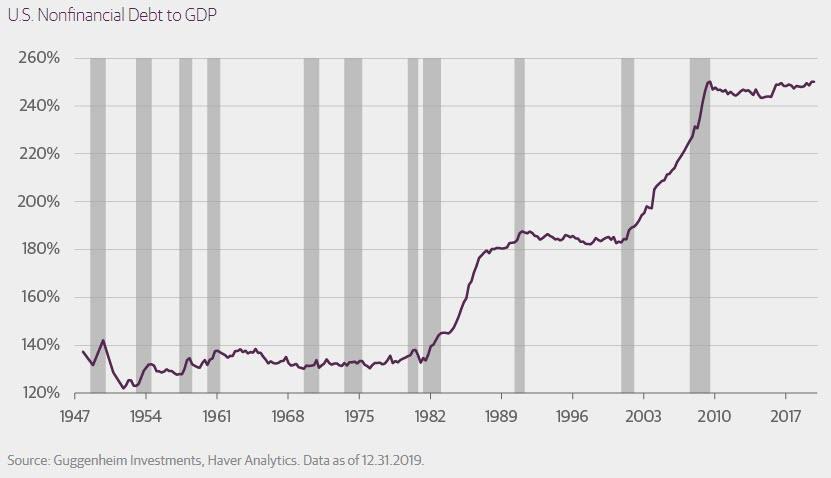

The policy of the central bank to continually step in, lower interest rates, and encourage companies and people to take on more debt has been in place since the 1930s. The idea that the central bank could push interest rates down and make more credit available to smooth out the business cycle is designed to have an economy that operates with fewer recessions, less severe recessions, and ultimately longer periods of expansion. This policy worked, but it also created the Great Debt Supercycle: Every time we get ourselves into a recession, the total debt of the U.S. economy rises relative to gross domestic product (GDP) to new and higher levels. This is not sustainable in the long run, even if we are able to push interest rates into significantly negative positions on a sustained basis.

Policy Drives the Debt Supercycle

“We are all Keynesians now” is the famous phrase attributed to Richard Nixon during the financial crisis of 1971 as a sign of his reluctant acceptance of an economic theory he found objectionable. I understand how he must have felt. I see lower interest rates coming and tighter credit spreads ahead. There may be hiccups along the way, but the resetting of valuations across most sectors has presented attractive opportunities and prompted us to significantly increase credit exposure. Our confidence is based on thorough credit analysis and informed relative value assessment. But it is also based on my reluctant acceptance of the policy framework that is now in place.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 05/11/2020 – 15:05