In Unprecedented Move, Two Fund Giants Liquidate CLO Warehouses

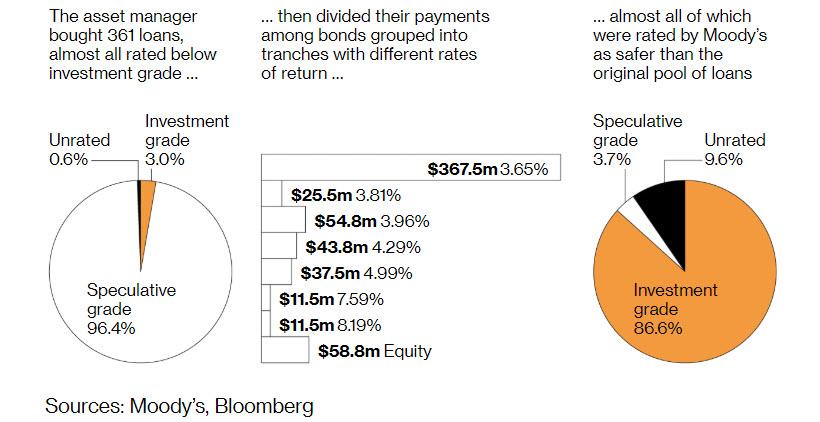

Yesterday we laid out how the magic of modern monetary alchemy (not to be confused with the blunt brain trauma that is the magic money tree of helicopter money) works, by showing how a CLO takes 96% junk rates loans and by repackaging this portfolio, or “warehousing” it into a CLO, the product were tranched bonds of which 87% were rated investment grade.

And while in theory this works by “diversifying” away individual credit risk, in practice the whole exercise is nothing but smoke and mirrors which crumbles the moment an adverse systemic event – such as a global viral pandemic – reveals that the investment grade emperor is really wearing junk-rated clothes.

Of course, it is the very process of warehousing that made all this possible and resulted in record demand for leveraged loans for the past few years, with CLOs becoming the biggest source of demand for the $1 trillion leveraged loan market, because as we concluded in our article, this CLO sleight of hand “worked splendidly as long as nobody questioned the “alchemy” behind the biggest magic trick Wall Street pulled in the past decade. Alas, alchemy does not exist, and just like all those buying “gold” from carnival charlatans eventually realized they were holding on to lead, so all those who naively believed they had purchased investment grade securities are about to learn the hard way that what they really owned was, aptly-named, junk.”

Fast forward to today, when investors finally appear to be asking what good are CLOs, and what is the point of tranching cash flows, if virtually all underlying junk loans will soon end up – true to their name – in default, with no cash flows left to tranche.

Bloomberg reports that two funds that aimed to bundle leveraged loans into bonds decided instead to liquidate the loans they had bought, a rare step reflecting just how the pandemic has cooled the market for securities known as collateralized loan obligations.

At a time of massive downgrades of both underlying loans and resulting CLO bonds, Steele Creek Investment Management and AXA Investment Managers both sold off loans they had planned to package into CLOs, according to Bloomberg citing people familiar with the matter. The funds had paid for the loans using temporary lines of credit known as warehouses.

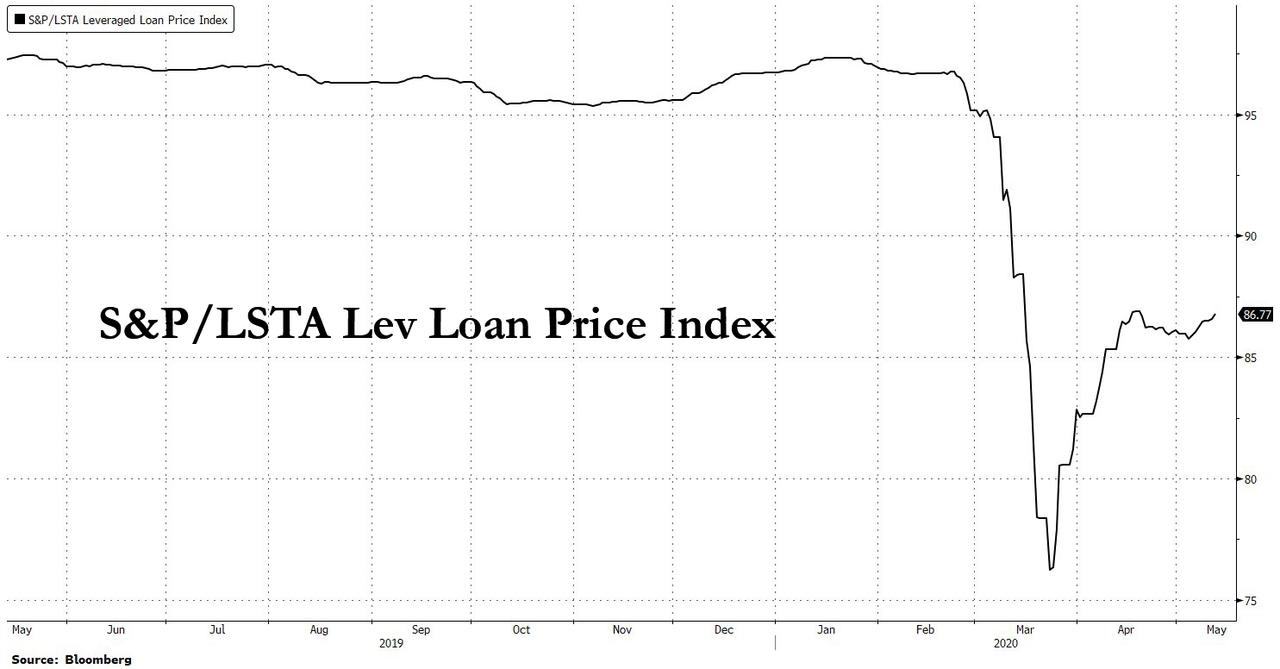

With leveraged loan prices plunged to their lowest level in more than a decade in March, CLOs have been left scrambling to find buyers for their securities, and as a result Steele Creek and AXA Investment Managers decided to instead liquidate their warehouses, a move that some investors fear may become increasingly common, and could push loan prices even lower.

Steele Creek, a Moelis Asset Management company, put a $177 million warehouse loan portfolio up for sale on May 4, the people said. A spokesperson for Steele Creek declined to comment. AXA’s asset management arm sold a warehouse for a CLO it was arranging with Citigroup, said the people, asking not to be identified discussing a private matter.

As Bloomberg notes, selling loans held in warehouses may make more sense now after prices have recovered somewhat from their March levels amid growing Federal Reserve support for credit markets, making potential losses relatively manageable, investors said.

In keeping with the intricacies of structured credit, a CLO warehouse is often funded in part by outside investors who bear the initial pain if the loans go bad, known as the first loss, similar to the equity tranche of the final CLO itself. They usually choose to roll their investment into the riskiest securities of a CLO when the deal is ready to close, known as the equity portion. AXA Investment Management’s decision was made in conjunction with, and in the best interests of the first loss provider, according to Yannick Le Serviget, the firm’s global head of leveraged loans and private debt. AXA IM declined to comment on specifics of the transaction.

“Given the large repricing of the loan market, specifically good quality portfolios, it did make sense to take advantage of the upward pricing,” Le Serviget said.

While such liquidations are extremely rare, fears of CLO warehouse unwinds emerged in March once pandemic fears started hammering corporate debt markets broadly. The, as we reported last month, ratings firms downgraded a wave of loans as the pandemic weighed on companies’ sales. The average loan price plummeted to around 76 cents on the dollar in late March, before rebounding to around 87 cents.

What makes the liquidation scenario especially concerning is that most CLO warehouses aren’t forced to sell loans if prices fall below particular levels, and since the facilities usually mature in 12 to 18 months, fund managers and investors have breathing room to decide whether to liquidate or go through with the CLO. Unwinding a facility at depressed prices could force some CLO investors to bear losses, making them less inclined to push for an unwind.

But investors in the CLO who are among the first to take losses might become more inclined to liquidate a warehouse if i) the loans become impaired, or if ii) they see little scope for price recovery over the medium term. In some cases it may also make more economic sense not to proceed with a transaction if there is a buyer for the loans in the warehouse, investors say. Banks may also pressure CLO managers to end deals if assets are sitting in a warehouse for too long.

The concern is that if despite the recent rebound in both loan prices and various CLO tranches, as per the Palmer Square index, two fund giants decided to unwind warehouses, then the signal is clear: this is as good as it will get for the leveraged loan market – i.e., this is the apex of the dead cat bounce – and what is coming will be much uglier.

* * *

The stunning move by Axa and Steele Creek may explain why on Tuesday, the Fed revised its Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility to allow CLOs that hold a broader range of leveraged loans to be used as collateral. According to a Fed statement, the central bank will now accept new AAA CLOs with leveraged loans, including refinanced loans, that priced as far back as January 2019, compared to the previous term sheet where eligible CLO could only hold newly-originated loans.

Still, the Fed’s involvement is largely superficial to the CLO market which until now had not benefited much from the central bank’s effort to boost credit liquidity: as Bloomberg notes, the terms still require eligible CLOs be static vehicles wherein managers can’t actively trade the loans underpinning the deals, a structure that makes up only a small portion of the market. “It’s not going to open up the floodgates, but it can have some measured effects,” said Gregg Jubin, a partner at Cadwalader. “This looks certainly better than the first iteration.”

It is hardly a coincidence that the Fed announcement comes just as a warehouse was liquidated. According to Jubin, the changes may benefit existing CLO warehouses that hold qualifying loans. On the other hand, some pointed out to the prohibitive interest rate demanded by the Fed under TALF , which will be 150 bps over 30-day average SOFR, making the facility quite expensive .

It’s “a positive sign for the market that the look back for eligible collateral extends back to the beginning of 2019 and also includes refinancings since that time, as is the fact that the Fed appears to have taken into consideration certain detailed aspects of how the CLO market operates,” said Nick Robinson, a partner at Allen & Overy LLP. And while this may be good news for investors in recent AAA CLOs tranches – mostly Japanese retirees – everyone else, i.e., all those who hold to AA and lower rated tranches, remain in the cold and will have to wait for the next crash in hopes the Fed expands the scope of TALF again, or else have no choice but to sell now that the AXAs of the world have suggested this is as good as it will get.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 05/12/2020 – 20:07