Japanese Farmers Lose $3.7 Billion In US CLOs, Are Done Investing In Crazy Products

Tyler Durden

Thu, 05/28/2020 – 17:41

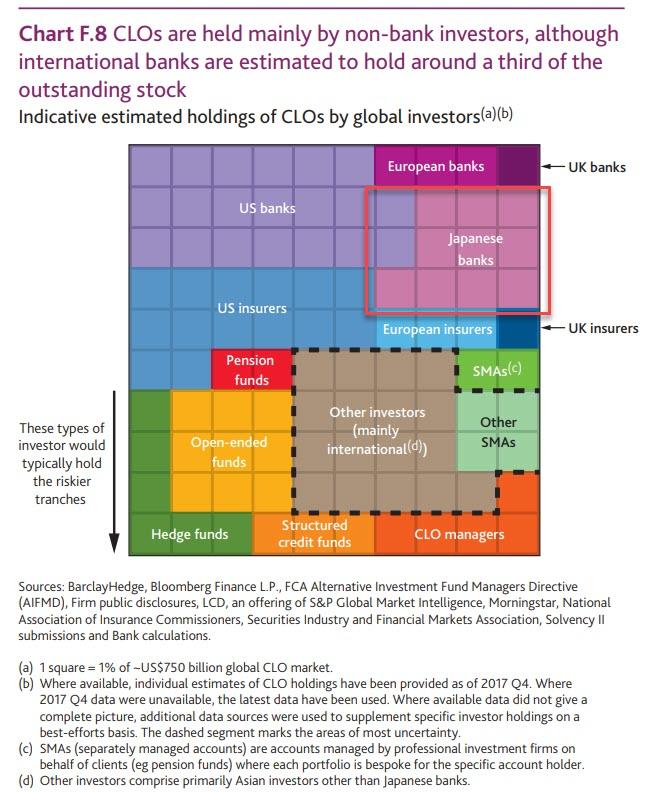

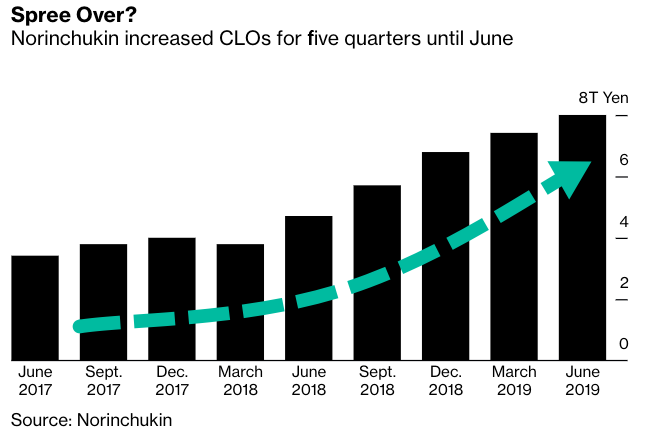

The last time we looked at the participation of Japanese banks in the CLO market, we found that they have historically been some of the largest buyers in the structured credit space, as many were forced to take on more risk in search of yield to cover rising hedge costs as the USD yield curve flattens late in the cycle. And here one bank stood out: Norinchukin Bank – better known as Nochu – a cooperative that invests the deposits of millions of Japanese farmers and fishermen, and which has emerged as the biggest CLO whale – had bought $10 billion of CLOs in the U.S. and Europe in the last three months of 2018, accounting for almost half of the top-rated issuance for the period.

How big is Nochu in the US CLO market? Let’s just say there is no single bigger player in the $700 billion CLO market, where until very recently it was buying as much as half of the highest-rated bonds in the fourth quarter of 2019 in Europe and the U.S, owning over $70 billion in CLOs, more than twice as much as the two other largest players combined, Wells Fargo and JPM, each of which owns about $30 billion.

Then, following the late 2018 crash in the leveraged loan market, Nochu’s appetite for structured credit quietly faded in mid-2019 after Japanese authorities tightened financial regulations.

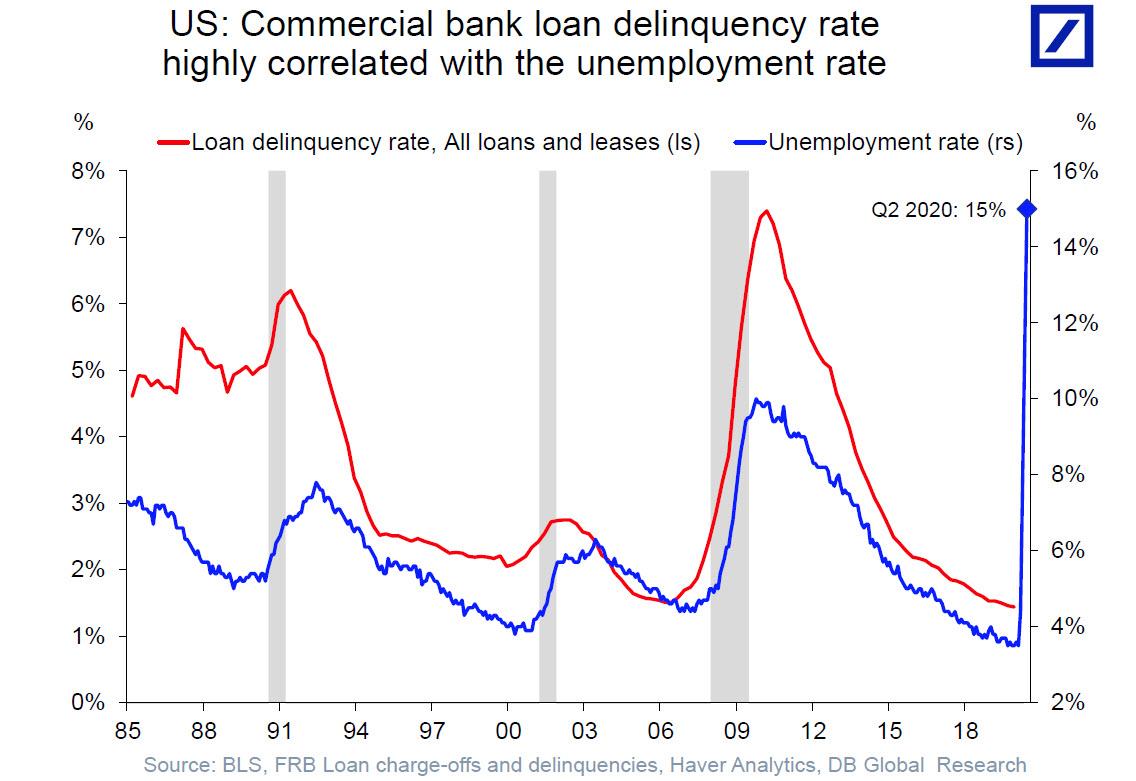

Alas, if Nochu though that its CLO troubles were behind it, it was in for the shock of a lifetime, because following the crash in the CLO market due to the recent covid shutdowns which have sparked an unprecedented crisis among the leveraged loan market, crippling cash flows and priming a bankruptcy wave the likes of which have never been seen before…

… the company that invests on behalf of millions of Japanese farmers, fishermen and retirees, suffered a record JPY400 billion ($3.7 billion) loss, and more importantly, announced it was no longer going to invest in such crazy products and was pulling out of the CLO market.

“We will limit making new investments” in CLOs, Chief Executive Kazuto Oku said.

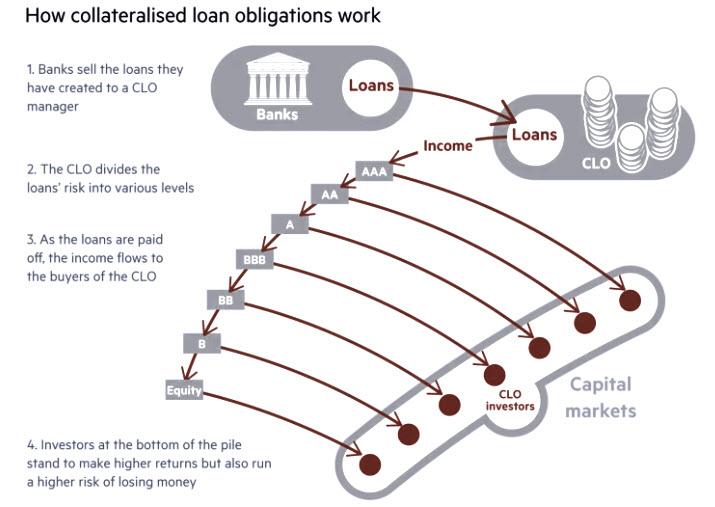

Norinchukin suffered nearly 5% losses on its $71 billion CLO portfolio despite being invested exclusively in the AAA-tranche of CLOs.

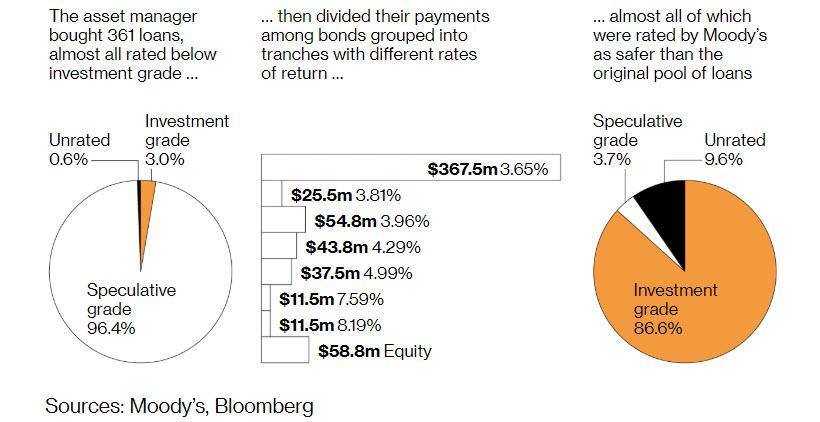

It was only recently that Wall Street found out about the massive role Nochu played in the CLO market, where it hoped to avoid Japan’s negative interest rates by buying “safe” structured credit tranches. Like most investors in the safe parts of CLOs, the banks have sought extra yield for the same level of risk. That strategy blew up in the financial crisis when supposedly safe securities backed by mortgages caused big losses for banks; and then it blew up again during the coronavirus crisis, when as we reported last month, something supposedly impossible happened: “A CLO Failed Its AAA Overcollateralization Test.“

This took place as an avalanche of default slammed the corporate bond and leveraged loan markets – with companies like Hertz and J.C. Penney filing Chapter 11 bankruptcy – prompting Moody to place the ratings on 859 securities from 358 U.S. CLOs, worth some $22 billion, on review for downgrade.

But where it gets really scary is that the “diversification” model behind CLOs, which we dubbed modern-day alchemy…

… no longer works when there is a uniform wave of defaults wiping out the cash flows of most companies that make up the structure obligation. The result could be a total wipe out to the very top of the bond stack created from the underlying junk loans.

Rod Dubitsky, who headed U.S. asset-backed securities research at Credit Suisse until 2009, confirmed as much saying that a critical risk right now is that the mathematical models that created the safe securities didn’t take into account a scenario like the coronavirus pandemic. Dubitsky argued back then that subprime mortgage-backed securities were due for a wave of downgrades, and he recently issued the same warning for triple-A rated CLO bonds. In a recent paper, he claimed that the securities don’t deserve such high ratings because of the impact of the pandemic on the economy.

“The entire concept of triple-A CLOs goes out the window because there is not much diversification left when the entire portfolio is subject to a global economy that is in deep recession,” Dubitsky told the WSJ in an interview, confirming precisely what we said three weeks ago.

Right or wrong, Dubitsky’s thesis will be tested very soon: in recent weeks, Moody’s, S&P and Fitch have collectively placed more than 1,600 bonds from mostly lower rated CLOs on review for possible downgrades.

Meanwhile, should other investors follow in Nochu’s footsteps and exit the CLO market, it could have catastrophic consequences for Wall Street, where CLOs have been the biggest source of funding for private-equity buyouts and a source of funds for struggling companies that are owned by PE firms. But there is another risk: if too many loans held by the funds are downgraded to the lowest levels, the funds may not be able to buy new loans, further tightening the lending markets.

But going back to Nochu, anb its chief, Oku, he sounded only slightly chastened by the losses, saying it was his job to extract return from the bank’s portfolio and pass it on to members.

“It is difficult to disagree with the opinion that we have to use member banks’ money more effectively instead of investing in overseas CLOs,” he said. “But we have to steadily try to make investments that are profitable.”

Ah yes, the old risk vs return calculus which unfortunately no longer works under central planning, as risk is either zero for along time, or virtually unlimited when central bank credibility is threatened.

Speaking to the Journal, Oku didn’t say what specifically caused losses in his bank’s portfolio, but he held out hope that his holdings might keep their value even in a bad situation. In any case, the bank was stepping away from new investments in that market, he said.

“We will have to examine risks in two stages: how many U.S. companies will go bankrupt or file for chapter 11, and after that, in how many of these cases we will see AAA-rated CLOs being affected,” he said at a news conference.

Ironically, even as Nochu waves goodbye to CLOs, it refuses to admit just how much it has lost: the bank isn’t reflecting CLO losses on its bottom line, suggesting that the pain is only now starting for millions of japanese retirees and savers who had naively believed that investing money in the scam that is the US structured market will make someone, besides the Wall Street bankers who arranged them or the companies that issued them, richer.

Norinchukin acts as a central pool for funds gathered by local farming and fishing cooperatives throughout Japan, and it holds $600 billion in deposits from member cooperatives. It can use the money to make loans to companies in farming, forestry or fisheries, or it can simply invest it in global markets like any money manager, apparently hoping to make money on CLOs.

The irony is that Nochu may not even have had much of a choice: its problem for years has been a shortage of loan opportunities – just the problem CLO managers love to fix – leaving the money-management side of the business as the dominant one. The number of people working in agriculture as their main job has fallen 35% during the last decade, and those who remain are mostly over 65.