Why The Recovery Will Fall Short Of Forecasts

Tyler Durden

Wed, 06/03/2020 – 13:25

Authored by Michael Lebowitz and Jack Scott via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

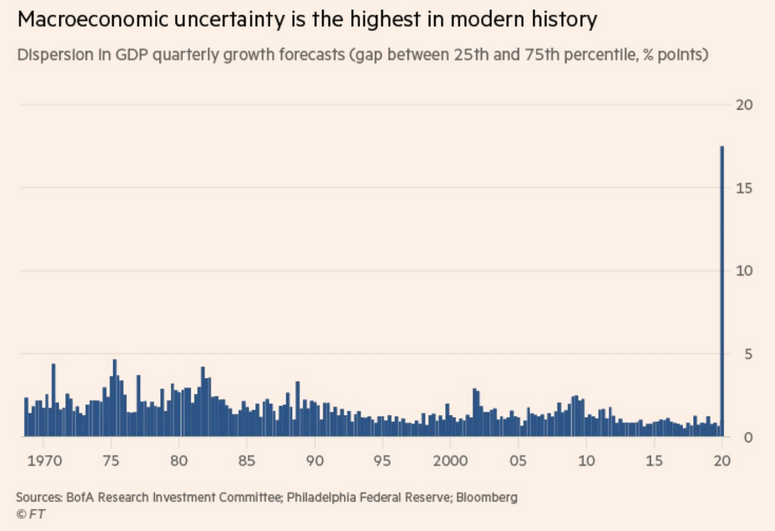

Market pundits seem to have strong opinions about how fast or slow the economic recovery will be once it starts. Such clairvoyance is stunning given the uncertainty of the current GDP forecast, which is already two-thirds in the books.

If the world’s leading economists cannot come to any consensus about today, why should we assume anyone has clarity for tomorrow?

We do not have great clarity either, but we can provide guidance using what we know about the past and present. Our logic presented here is grounded in optimistic assumptions and historical data. The result is an outcome that is well below the hope-based forecasts of most economists.

Quite frankly, what we present today may be the best possible scenario. It strays far from the popular narrative but deserves serious consideration.

Alphabet Economy

Will the economy recover in “V”, “U” or “L” – shaped fashion?

We hope for a speedy “V”-shaped recovery, but we are realists and understand that the odds of quickly rekindling the economic growth rates from the prior decade are poor. Our stark assessment is due to numerous factors that existed well before the virus and the extreme fiscal and monetary policy responses to the virus.

The last sentence is loaded. We will follow it up in future articles explaining why a full recovery is so difficult. In the meantime, we present a simple economic model, using very optimistic assumptions showing why this recovery is likely to be measured in years, not months.

It is important to stress; the assumptions in our model are the best case. It is easy to come up with more severe scenarios.

GDP

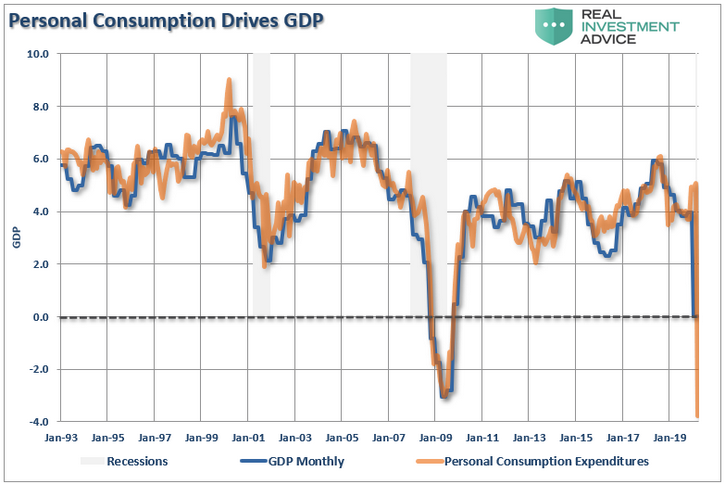

Gross domestic product (GDP) is how economic activity and growth are quantified. GDP is the sum of personal consumption expenditures (PCE), gross business investment, net government spending, and the amount of exports less imports.

The most substantial weighting in GDP is personal consumption expenditures (PCE). Over the prior economic expansion, lasting a decade, PCE constituted 74% of GDP. Since 1948, it has averaged 65%.

The outsized significance of consumption and the secondary effect it has on the other contributors to GDP, allows economists to use PCE as a proxy to forecast economic growth. Statistically, using three-year moving averages, PCE and Real GDP have a correlation of .7789.

Jobs > PCE > GDP

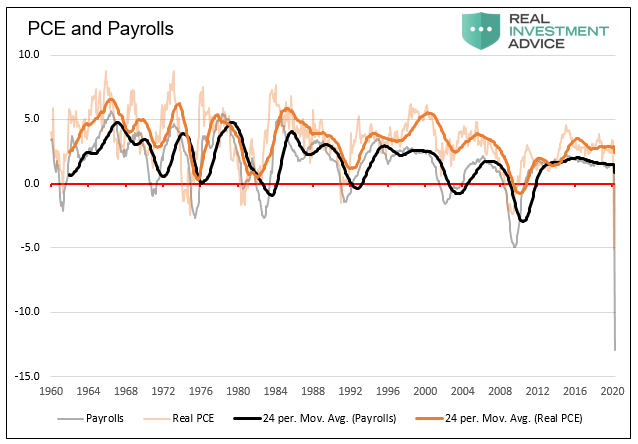

As PCE drives GDP, labor drives PCE. The vast majority of families in the U.S. work to consume. Some wealthy households can rely on investments and savings, and some poor citizens depend on the government. However, the large majority of citizens must consume its wages. Accordingly, PCE is mostly a function of employment and the size of our paychecks.

The graph below shows the year over year change in the number of employed versus the year over year change in PCE. When averaged over two years, as the darker lines show, the correlation is clear.

Forecasting Employment

Given the strong relationship between the labor market and consumption, we can use labor forecasts to arrive at PCE estimates. This is a two-step process.

First, current data and near-term expectations afford a forecast for when and at what level the labor market may trough. Second, we use prior recession data to calculate the rate at which the labor market may recover from the trough.

Step 1– As of the April 2020 BLS jobs report, the number of people counted as employed fell 13.5% to 131 million. Economists expect it to fall another 6% to 123 million when the May report is released this Friday. We aggressively presume that the May report will mark the low point in jobs and that the number of employed will increase going forward.

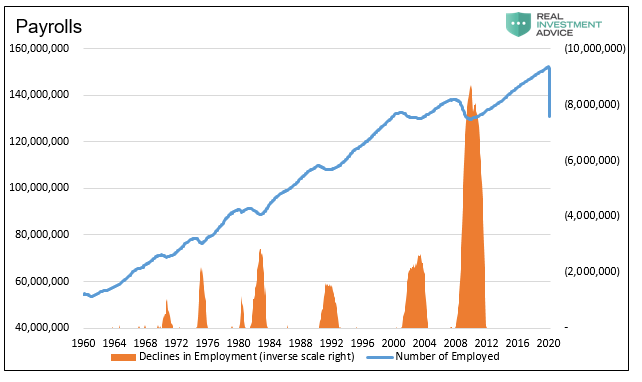

Step 2– The graph below helps illustrate the rate in which job growth might return to its prior peak. The orange bars show the depth of employment losses in terms of number and time. We invert the second y-axis for comparative purposes.

The most recent, 2008/09 recession, took 76 months for the number of jobs to go from peak to trough and back to the prior peak.

2008

When considering the last three recessions, the recession of 2008/09 is the best proxy to model future expectations. Not only was it the most recent recession, but it best captures our current mindset and economic standing.

-

The recession was broader based, and affected more industries, citizens, and nations, than the prior recessions of 1990 and 2001.

-

The 2008/09 recession and recovery also required significantly more fiscal and monetary policy to boost economic activity.

-

The amount of federal, corporate, and individual debt was significantly lower in 1990 and 2001 then 2008/09.

-

The natural economic growth rate for 1990 and 2001 was higher than the rate going into the 2008/09 recession.

Our current economy is saddled with more debt than the last recession, and the natural rate of growth has diminished over the previous ten years. As we will share in a future article, the economic growth rate going forward may be half of the already weak pace heading into the current recession.

As has progressively been the case, new debt issuance to fight the current recession will cost us in the future. Accordingly, we think the 2008 experience is an optimistic proxy to analyze the time and rate at which the labor market might recover. In fact, The 2008/09 scenario may likely be the absolute best-case scenario. The number of job losses is already much more severe than that seen in the financial crisis, and the duration of the recovery seems certain to be longer than that episode.

In the 2008/09 recession, the payrolls number troughed two years after the recession started, falling 6.3% from the prior peak. From that low point, it took over four years for the labor market to fully regain the losses. In total, the labor market required six years to recover the pre-recession peak.

2020

The number of people the BLS considers employed peaked in February 2020 at 156.463 million. It dipped by a little less than one million in March and then plummeted in April by over 25.4 million to 131.045 million.

Today, the range of estimates for the number of current employees is wide. For our analysis, we assume that the May jobs report will mark the trough. The current estimate for the number of employed is 123 million.

Putting 2 and 2 Together

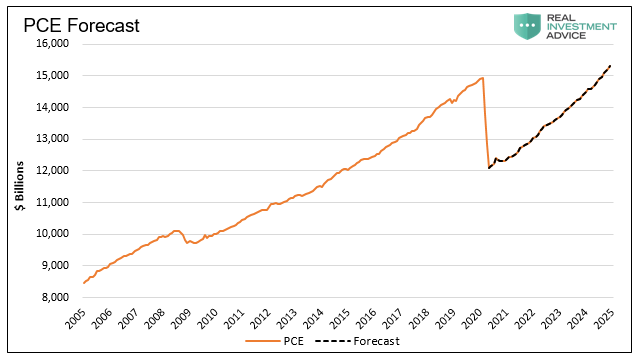

To review, our forecast assumes that jobs will trough in May. From June going forward, jobs will recover at the same rate and duration as in the aftermath of 2008. Using this assumption we create the PCE forecast shown below.

If the historical relationship between labor and PCE holds up, and consumption continues to be the predominant contributor to GDP, we should not expect GDP to regain prior highs until 2025.

Summary

The recovery we laid out above is not a “V” or “U” shape. It resembles the Nike swoosh logo with a sharp decline and a long period of recovery.

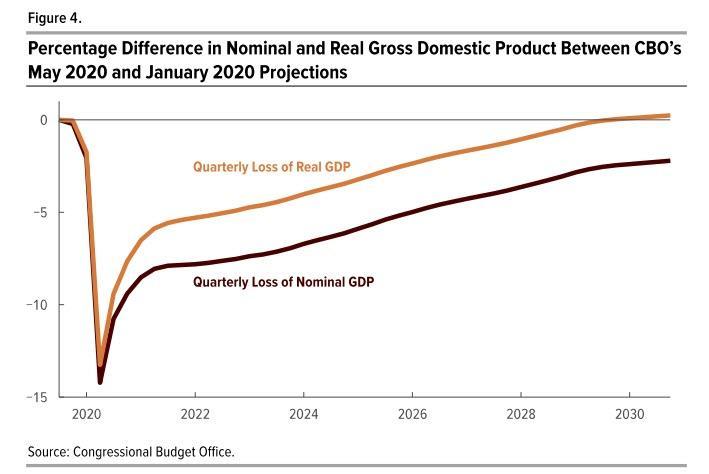

Interestingly, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) agrees with us in that recovery will be much longer than most economists forecast. The CBO’s Nike swoosh forecast below shows the economy will not fully recover for at least a decade.

As mentioned, this analysis assumes a recovery akin to what the economy experienced in 2008. While 2008 was tough, the natural rate of economic growth at the time was more robust and the amount of debt was less.

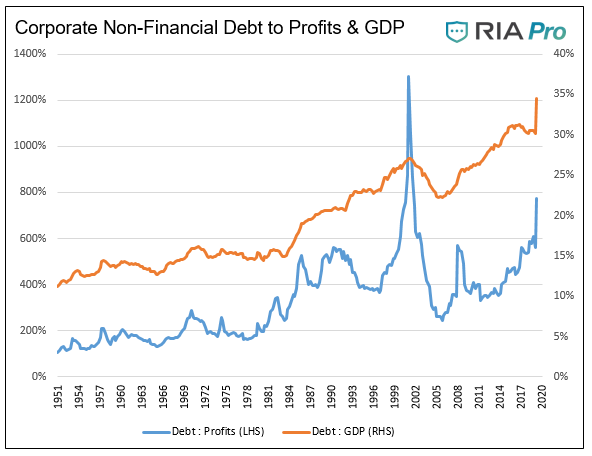

Since 2008, the ratio of Federal debt to GDP has almost doubled. It now sits close to 120%, well beyond the rate that many economists consider sustainable. Corporate debt to GDP and profits are also growing at unsustainable rates, as shown below.

The simple takeaway is that debt will weigh even more heavily on the current path of growth as the economy recovers.

Economists, when forecasting economic activity, often fail to account for the existing headwinds fully and rarely the new ones. Are they willfully ignorant, or might their employers have a vested interest in portraying a favorable outcome?