Civil Unrest

Tyler Durden

Wed, 07/15/2020 – 20:10

Authored by Philip Marey, Senior US Strategist at Rabobank

Civil Unrest

Summary

- In contrast to most other developed countries, the first wave of COVID-19 has not been suppressed in the US. Both at the federal and state level institutions are failing.

- Protests against COVID-19 measures and against racism reflect a lack of trust in US institutions that predates the outbreak of the virus. In a polarized society trust in institutions is likely to be vulnerable.

- No matter who wins the elections, the turbulence in US politics and society is not likely to pass. In fact, what we are seeing now may be only the beginning.

First wave failure

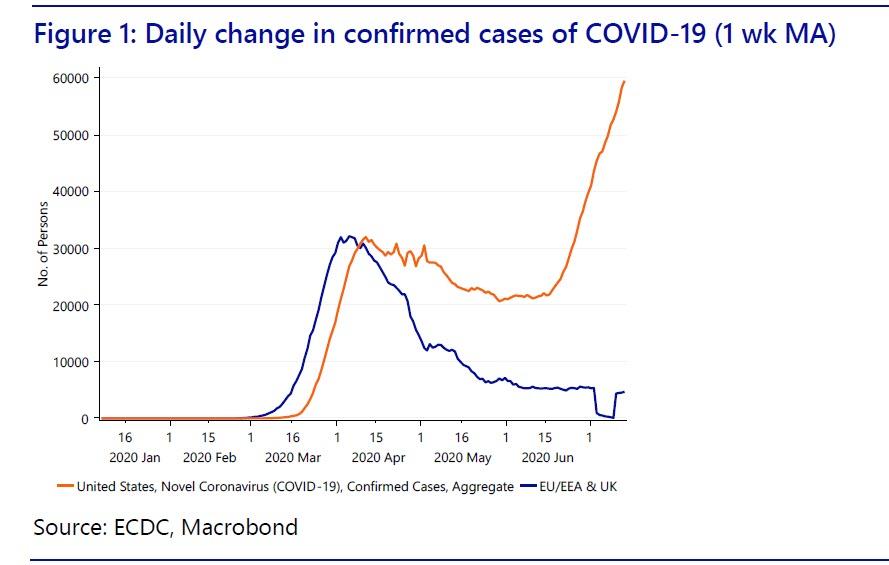

In the last months we have seen the US taking a descent into chaos. In contrast to most other developed countries, the first wave of COVID-19 has not been suppressed. In fact, in June the daily amount of new confirmed cases surpassed the initial peak reached in April. At the same time, a coherent federal plan to turn this around seems lacking. At the state level, economies have been reopened before meeting the criteria set out earlier by the White House. At the individual level, we have seen many protests against measures to contain the virus.

Stop the killing

Meanwhile, protests of another nature have taken over the streets. The endless series of police killings finally sparked a national outrage when images of the Minneapolis police murdering George Floyd were seen around the world. Of course this was nothing new. In fact, over the years many black Americans have lost their lives at the hands of the police. In most cases, the police got away with it. However, in this age of smartphones with cameras and social media, white Americans finally saw what black Americans experience.

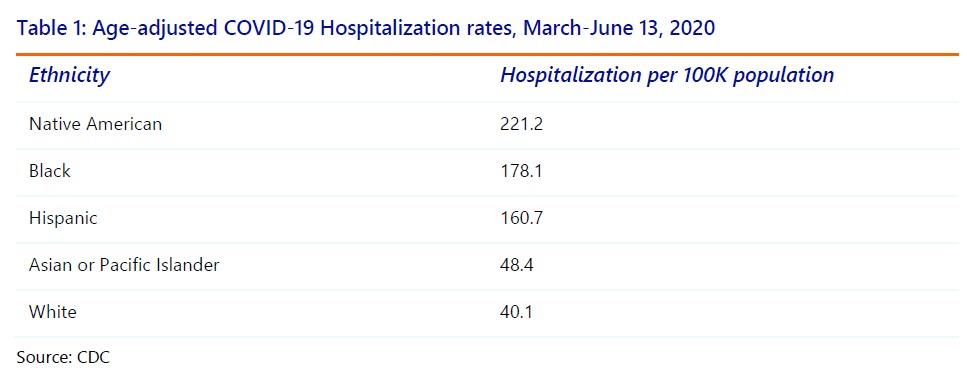

Earlier during the coronacrisis, the second rate US citizenship of black Americans was evident in the asymmetric impact of COVID-19 that we noted in the April Monthly Outlook. According to CDC data (Table 1) black Americans have a COVID-19 associated hospitalization rate almost 5 times that of white Americans, adjusted for age. In fact, for native Americans this ratio is even higher. Living conditions, work circumstances and healthcare inequities put several ethnic minority groups at increased risk during COVID-19 according to the CDC.

V or W?

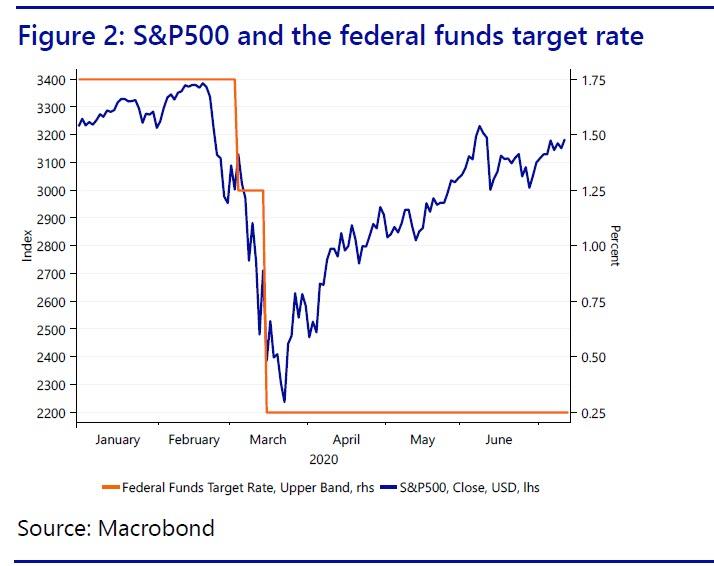

In sharp contrast to the widely broadcast civil unrest, stock markets have rebounded rapidly and the economic data for May and June suggest that the real economy is following. However, we should note that the recovery in the stock markets did not start until after the Fed had cut rates to zero, announced QE Infinity and launched its special lending facilities, which included corporate bonds. The recovery in the real economy follows a sharp contraction caused by the outbreak of COVID-19 and the lockdown that followed. The decline in economic activity in March and April was so steep that it caused both Q1 and Q2 GDP growth to be negative. The rebound we are now seeing is simply the effect of opening up the economy again. This is a mechanical rebound, and as we explained in The Recession of 2020: The Horror Version, we will have to wait until Q4 before we could see demand fluctuations determine GDP growth again. Then we will see how much damage really has been done.

Crumbling institutions

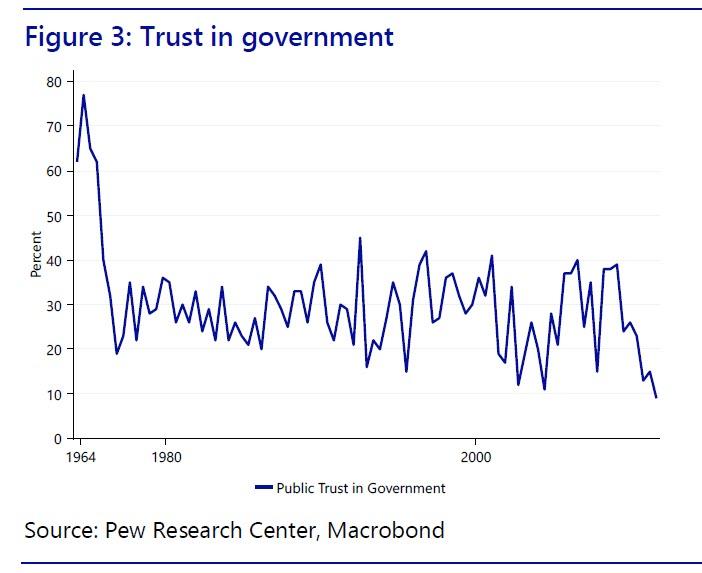

So at the moment there is this sharp contrast between the economic data and stock price levels on the Bloomberg screens and the images and discussions on TV. Note that both types of protests we mentioned, against COVID-19 measures and against racism, reflect a lack of trust in US institutions that predates the outbreak of the virus. In fact, data collected by the Pew Center show that trust in the federal government has fallen since the mid-1960s. In terms of economics, institutions are not working for Americans, unless you are one of the 1%. In terms of civil rights, institutions have failed black Americans and native Americans in particular.

Polarization

What’s more, in a polarized society trust in institutions is likely to be vulnerable. US politics has become polarized. Today, liberals vote for the Democrats and conservatives for the Republicans. This was not always the case however. In the 1950s there were liberals and conservatives in both parties. In fact, while many millennials regard the Democratic party as a beacon of political correctness, this party was a broad coalition that included Southern segregationists (= white supremacists) until the 1960s. Also, both in the Senate and the House of Representatives a higher percentage of Republicans voted for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 than Democrats. However, when Southern Democrats started to switch to the Republican Party after the Civil Rights Act, Northern liberals switched to the Democratic Party and this led to the sorting of liberals and conservatives between the two parties. Subsequently, the two parties were also sorted by race, religion and geography. This sorting process was a prelude to the polarization between the two parties. Political affiliation became part of someone’s identity. This also led to an increased aversion to the other party. The tone between the left and the right has become increasingly hostile. In light of this the polarization that we have seen in recent years is not caused by Trump, rather it is the other way around. The election of Trump is a consequence of this historical process. Polarization made it possible.

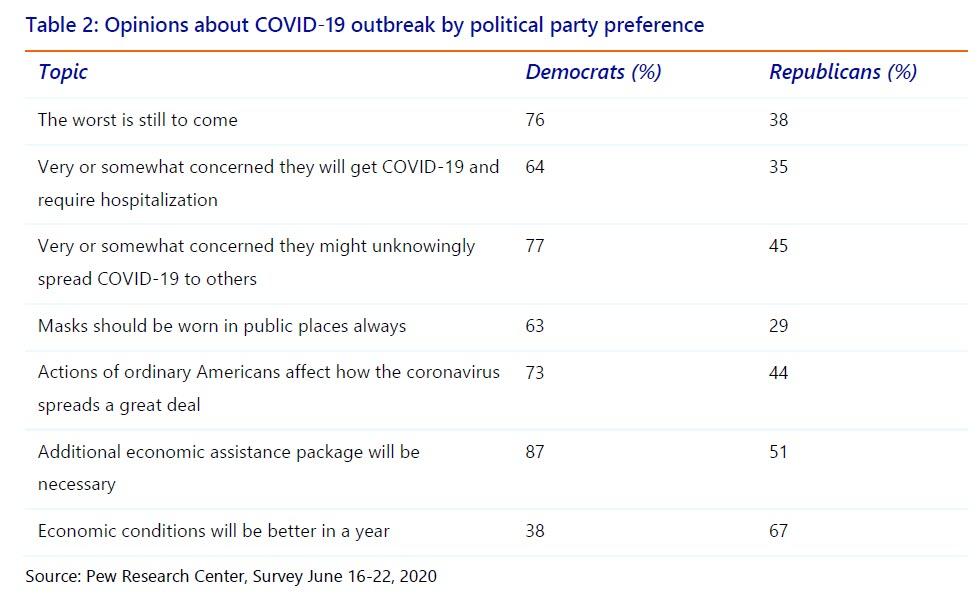

Moreover, polarization is even visible in opinions about the coronavirus outbreak (Table 2). With a lack of direction from the federal government, this makes a coherent national policy to get the outbreak under control very difficult.

Only the beginning?

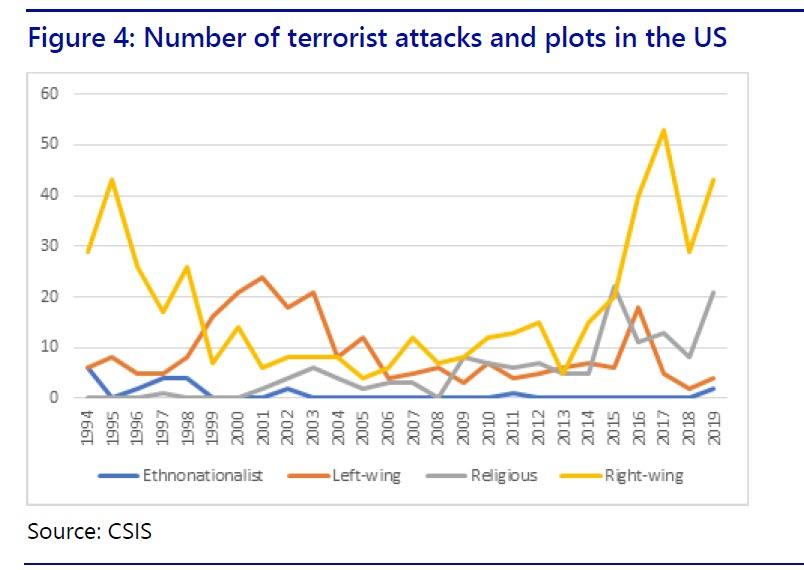

The question is where does the US go from here? If President Trump is re-elected, he will be at the wheel for four more years, but this time without any restrictions imposed by concerns about re-election. If Biden takes the White House, federal policies will shift to the left again (for more details see the May Monthly Outlook). But will this lead to renewed trust in institutions? Perhaps for some on the left, but what about the rest? In a heavily polarized country, there is little common ground. Meanwhile, if right-wing populism is expelled from the White House, this does not mean it is going to disappear. It will only reorganize. Hopefully in the political arena, but we could also see another boost to violent right-wing extremism. In fact, right-wing attacks and plots account for the majority of terrorist incidents in the US since the mid-1990s. In the last six years, this has grown substantially (Figure 4). So no matter who wins the elections, the turbulence in US politics and society is not likely to pass. In fact, what we are seeing now may be only the beginning.