Levine: Reading The Market’s Postmodern Mind

Tyler Durden

Thu, 07/23/2020 – 21:50

Authored by Seth Levine via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

No matter how you slice it, markets are human. This even applies to the “algos” as it’s we who write their mechanistic marching orders. Thus, understanding human behavior can be helpful in assessing and anticipating market moves. There’s no choice in the fact that we all need a philosophy to live. The same holds for investing. Thus, understanding the dominant market philosophies can potentially give us an investing edge. We can thank Tony Greer, the editor of the Morning Navigator, for doing just this.

In a recent Hidden Forces interview, Greer casually states the following:

“I’ve been calling it financial postmodernism, Demetri (emphasis added).

And I call it that because we just came out of a scenario where as we were getting the actual read on what the lockdown did to the economy and those literally ghoulish economic data numbers, the stock market was putting in massive upside rallies, right? And it was rallying off of the lows and it was rallying off of a spike low. So, it looked even more obnoxious that Wall Street is celebrating while Main Street is getting crushed. And that was sort of the new dichotomy that happened right through, jeez, I guess through April, May, and right into June. Where you’re getting an economic data point on Friday of 9 million people unemployed and nonfarm payrolls and you’re getting the S&P up 6% in the same day against the headlines of Dow up 1,000 on CNBC.

And people are like, ‘What the hell is going on here? What? Does Wall Street not care? Does the market not care?’”

Tony Greer, Hidden Forces Episode 142

Greer’s characterization of today’s investment markets as financial postmodernism is as genius as it is obscure. Since mentioning it, I see parallels between today’s investment markets and the postmodern philosophy everywhere. Perhaps teasing out Greer’s identification can help make better sense of these seemingly insane investment conditions.

What is Postmodernism

Only recently did I stumble upon postmodernism. I never heard the term before and suspect few outside the halls of academia have either. While largely unknown, it’s hard to escape postmodernism’s effect on the culture. Investment markets are just one manifestation.

Postmodernism is an intellectual movement with roots dating back to the 1950s in America. It’s a mixture of philosophy and history that underpins much of the modern culture, and especially the political Left. While postmodernism’s intellectual leaders may not be household names, many postmodern ideas are unfortunately commonplace. These include the beliefs that the U.S. is fundamentally racist, sexist, and shallowly materialistic; that Christopher Columbus is a villain; that one’s ethnicity or race define one’s politics; that Western nations exploit the less developed, and; that humans are a scourge destroying the planet.

My introduction to postmodernism came via Stephen Hicks. Hicks is a philosophy professor and author. His book Explaining Postmodernism masterfully does just that. It both outlines postmodernism’s core tenets and maps its historical lineage from the end of the Enlightenment up to the present day.

According to Hicks:

“Postmodernism’s essentials are the opposite of modernism’s.

Instead of natural reality—anti-realism.

Instead of experience and reason—linguistic social subjectivism.

Instead of individual identity and autonomy—various race, sex, and class group-isms.

Instead of human interests as fundamentally harmonious and tending toward mutually-beneficial interaction—conflict and oppression.

Instead of valuing individualism in values, markets, and politics—calls for communalism, solidarity, and egalitarian restraints.

Instead of prizing the achievement of science and technology—suspicion tending toward outright hostility.”

Stephen Hicks, Explaining Postmodernism

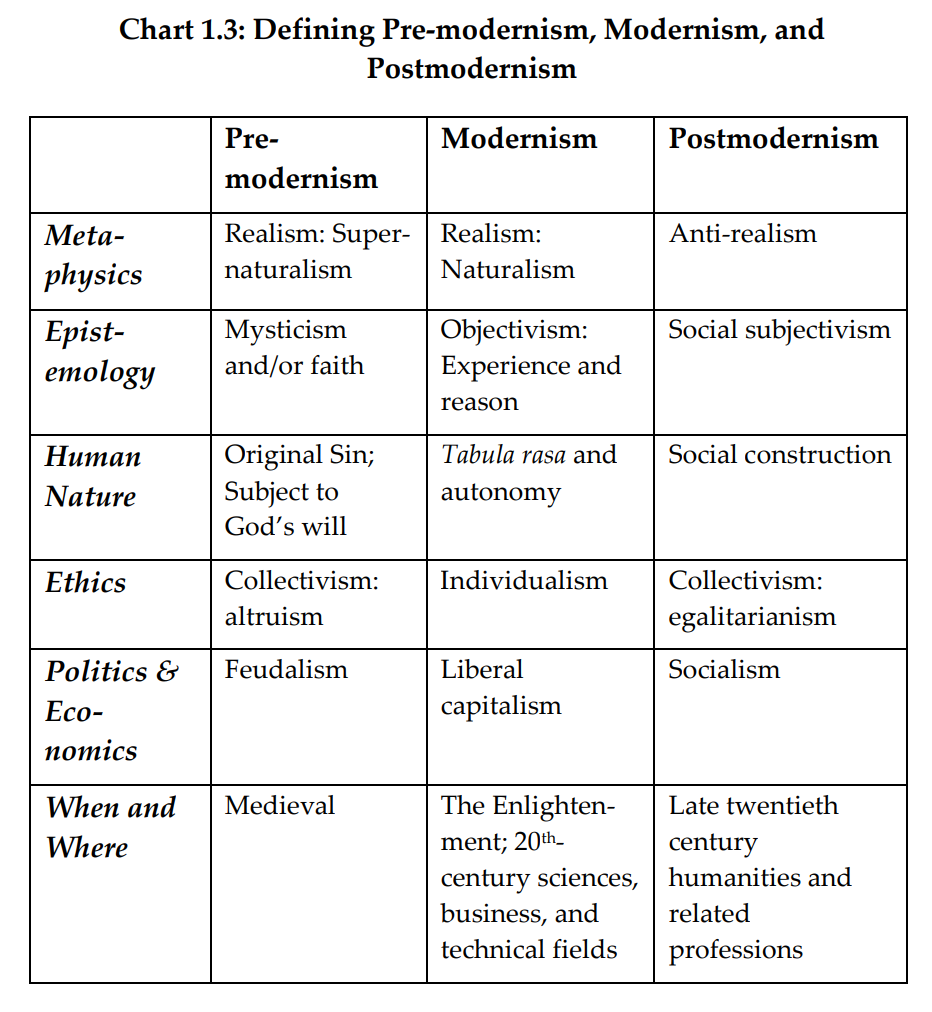

The following chart compares postmodernism’s perspectives with preceding philosophies’. Note that Hicks uses “modernism” synonymously with Enlightenment ideas and ascribes “pre-modernism” to the dominant intellectual framework from 400 to 1300 CE.

Source: Explaining Postmodernism

Hicks’s summaries are heavy, even for those steeped in philosophy. Nonetheless, the above is a useful framework for examining the zeitgeist of the financial markets. Let’s take it one step at a time to tease out postmodernism’s various influences.

Metaphysics

Metaphysics sits at the base of all philosophic systems. It describes the nature of existence (the “meta” moniker is not ironic). For example, are things simply as they appear (A is A in Aristotelian parlance), or can supernatural forces alter the natural world that we perceive? Hicks describes the postmodern view as:

“… anti-realist, holding that it is impossible to speak meaningfully about an independently existing reality. Postmodernism substitutes instead a social-linguistic, constructionist account of reality.”

Stephen Hicks, Explaining Postmodernism

To me, anti-realism is the perfect description for today’s markets. Many people assume that markets must continue to rise. That’s what they’ve always done so that’s what they’ll always do. It’s just the way the world works. The underlying causes and possibilities for change are almost ignored. Then there are those who see markets as distorted and disconnected from economic realities. Central banks and covert “plunge protection teams” are backstopping the equity markets to ensure that they never decline. There’s no other explanation for their behavior given the mess the economy is in.

To be honest, I see partial truths in both arguments. There’s plenty of evidence for there being a “Fed put” and Donald Trump does make every attempt to pump the stock market. However, human prosperity continues to advance and there could be other potential reasons for the stock market’s unrelenting rise (i.e. financial asset creation is lagging wealth’s).

Regardless, the market simply is; it is an immutable fact. Treating it as such is a realist perspective. Rather than looking to conspiracies or a long term trend line that ignores the path dependency of returns, this perspective should simply try to uncover the current market drivers and probabilities for change. To contest its state is to contest reality. It is an anti-realist stance.

Epistemology

Epistemology is another philosophy concept that I needed to look up two or three hundred times before I grasped its meaning. It’s the science of knowledge formation. In other words, epistemology examines how we uncover truths about the world. Do we learn by using the scientific method or do we receive wisdom from revelations; and is there even such a thing as truth to begin with?!

“To say that we should drop the idea of truth as out there waiting to be discovered is not to say that we have discovered that, out there, there is no truth. It is to say that our purpose would be served best by ceasing to see truth as a deep matter, as a topic of philosophic interest, or ‘true’ as a term which repays ‘analysis.’ ‘The nature of truth’ is an unprofitable topic, resembling in this respect ‘the nature of man’ and ‘the nature of God’ …”

Richard Rorty, Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity

According to postmodernism, there is no such thing as “truth.” Knowledge comes from consensus. Thus, reality can be whatever we want it to be, so long as enough people believe it.

How true this rings in today’s world of endless market interventions. Central banks have adopted zero and negative interest rate policies, and are voraciously buying sovereign bonds, mortgage bonds, corporate bonds, “junk bonds”, exchange traded funds, and even equities outright (as of this writing, the Swiss National Bank is a top 30 shareholder of Apple according to Bloomberg). What’s the reason for all these drastic actions? Well, because this misplaced concept of inflation is apparently undershooting some arbitrary target of course! (Huh?)

Sadly, there is little concern for the separation of governments from the capital markets. This feature is conveniently ignored as if it were an accident. So long as we believe these interventions produce prosperity it must be so. Never mind that monetary policy is just another price control with predictable effects; or that any attempt to tip the scale of markets only acts to destroy them and the immense prosperity they produce. We simply wish it were different so it must be so. Truth shmuth. This is the essence of social subjectivism.

Human Nature

We can even see hints of Postmodernism in how we view markets themselves. According to Hicks, postmodernism sees humans as pertaining to different groups that are in constant conflict. There are no individuals acting according to their own mind or for mutual benefit. Life is merely a zero-sum, social construction made up of competing teams.

“Postmodern accounts of human nature are consistently collectivist, holding that individuals’ identities are constructed largely by the social-linguistic groups that they are part of, those groups varying radically across the dimensions of sex, race, ethnicity, and wealth. Postmodern accounts of human nature also consistently emphasize relations of conflict between those groups; and given the de-emphasized or eliminated role of reason, postmodern accounts hold that those conflicts are resolved primarily by the use of force, whether masked or naked; the use of force in turn leads to relations of dominance, submission, and oppression.”

Stephen Hicks, Explaining Postmodernism

This collectivism and conflict have analogues in financial markets. We rarely describe them as beneficial methods for allocating capital to individual companies, countries, and entities. They are more commonly considered ways to disperse wealth among competing interests. The characterization takes various forms such as profits vs. wages, shareholders vs. other “stakeholders”, Wall Street vs. Main Street, “labor” vs. “capital”, and so on. Furthermore, only governments (i.e. force) can possibly arbiter these perceived conflicts. We must breakup “Big Tech” monopolies, regulate business, and “nudge” people in the direction of the “common good.” Left to his/her own devices, the free human would destroy financial markets, modern economies, and the planet. Thus, the intellectual elite, who somehow lack these intrinsic faults, must plan every action.

Ethics

Ethics is the science that studies how we should act. Our defined purpose for living frames the context for these decisions. Thus, you will come to a different moral code by making your own happiness paramount than by putting all others’ first (and your’s last).

Hicks describes the postmodern take on ethics as egalitarianism. Here, the belief in equality does not mean political equality, but rather a metaphysical equality. In other words, it’s not that we’re unique individuals who should be treated equally under the law; it’s that we’re literally all the same: physically, emotionally, and spiritually. We differ only by our various group identities (but are interchangeable within our belonged tribes). Individual values are a myth.

In my view, there’s a parallel to passive investing. Today’s investing context is quite small. Only returns and price fluctuations (i.e. volatility) matter. What’s your Sharpe ratio? If its worse than passive indices with higher fees, watch out, outflows will likely follow.

While maximizing returns is a key investment goal, it is not the only one. The value of investing cannot be divorced from the investor. Investing—like all actions—serves a purpose to an entity (person, pensioners, etc.). These needs are individualized. Why should every portfolio maximize its Sharpe ratio? To be sure volatility is a admirable attempt to quantify investment risk. However, there’s a whole host of other attributes like liquidity, governance, and political environments that may also suit an investor’s preferences. While I’m sympathetic to the case for passive investing, I take issue with its limited dimensionality. It paints everyone’s financial values with the same brush. This is the spirit of egalitarianism.

Politics and Economics

Politics describes the appropriate rules for governing human social systems. Thus, it follows from one’s deeper philosophic principles; politics do not stand on their own. Capitalism is the application of individualism in ethics to a group setting. Collectivism (socialism, communism, fascism, etc.) results from viewing people as parts of various factions. In other words, what we think of the goose dictates our prescriptions for the gander.

According to Hicks, postmodernists are rationalizing socialists. Their world views logically lead them to collectivism. However, the postmodernists have a problem. Socialism’s historical record is disastrous. Whenever (and to the extent) it’s been implemented, misery, poverty, death, and destruction have followed. Furthermore, not only have dire predictions for capitalism failed to materialize as postmodernists expect, but it created unimaginable prosperity.

What’s a postmodernist to do when his/her beliefs are in such stark conflict with reality? Simple, just ignore facts and invent a good narrative. After all, there is no truth, so go spin a good story and exercise some power.

“Postmodernism, Frank Lentricchia explains, ‘seeks not to find the foundation and the conditions of truth but to exercise power for the purpose of social change.”

Stephen Hicks, Explaining Postmodernism

What could be more postmodern than Mario Draghi’s “whatever it takes” speech. Given in a July 2012 address at the Global Investment Conference in London, the serving President of the European Central Bank (ECB) stated the following with respect to the European Union:

“When people talk about the fragility of the Euro … very often non-Euro area member states or leaders, underestimate the amount of political capital that is being invested in the Euro. … Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the Euro (emphasis added). And believe me, it will be enough.”

Mario Draghi

Draghi’s comment is laughable. Maintaining the Euro is well beyond the ECB’s power to control. However, it’s a clear instance of rhetoric trumping facts. There are plenty more. Take quantitative easing (QE) for example. It’s failed to deliver on its original promise and only resulted in more. How about Japan’s monetary policies? They are the model for most major central banks, yet the Bank of Japan’s efficacy is wholly ignored. It’s as if central banks throughout the Western world are simply competing to one-up the next. There’s no evidence that their theories are correct. Yet, they remain popular.

There are other ways too. Failure is not tolerated. In policy, it’s ignored. In industry and markets, pain is collectivized for the greater good of “the economy”, or “the workers”, or “the nation”, or pick your group. Bailouts are now commonplace. Policymakers and central banks reflexively act to prop up all markets, as one. We’re a far cry from capitalism.

When and Where

Just as postmodernism got its start in the late 20th century, so too did the current market’s philosophy. While Alan Greenspan’s reign as Fed governor may seem like its origin—after all, he’s the father of the “Fed put” due to his attempts to prop up investment markets—I believe Richard Nixon’s presidency is a better starting point.

It was Nixon who ushered in the modern era of fiat currency. By removing the dollar’s objective standard of value, its worth became completely subjective. We now must rely upon official releases riddled with vague adjustments to gauge its purchasing power. We can’t ascertain it ourselves. The dollar became a social construct! This lack of objectivity, self-reliance, and autonomy has postmodernism’s fingerprints all over it.

Our Postmodern Markets

The financial postmodernism that Greer astutely notes is merely a reflection of the culture. Many of the philosophy’s absurd beliefs have parallels in the investment markets. This manifests in heavy-handed regulations, endless interventions, and a neurotic obsession with markets’ continual rise to name a few. The investment markets are a far cry from a capitalist utopia—no surprise given our world views.

As investors, identifying the dominant ideas being expressed in the economy can be a useful edge. After all, markets are nothing more than an aggregation of human interactions. Understanding how an investment culture behaves might allow us to better anticipate how investors will integrate new information into price movements. These fluctuations may differ whether pre-modernist, modernist, or postmodernist principles are dominant. Greer’s anecdote illustrates this perfectly. The equity market rise following “literally ghoulish economic data” surprised many.

To be sure, this is a complex research topic worthy of deep exploration. We merely scratched the surface in this article. Hopefully though, we uncovered some ideas that can help us better read the market’s mind, see around corners, and grow our p&ls.