China’s Central Bank Has Quietly Launched Its Own QE

Tyler Durden

Wed, 08/12/2020 – 21:25

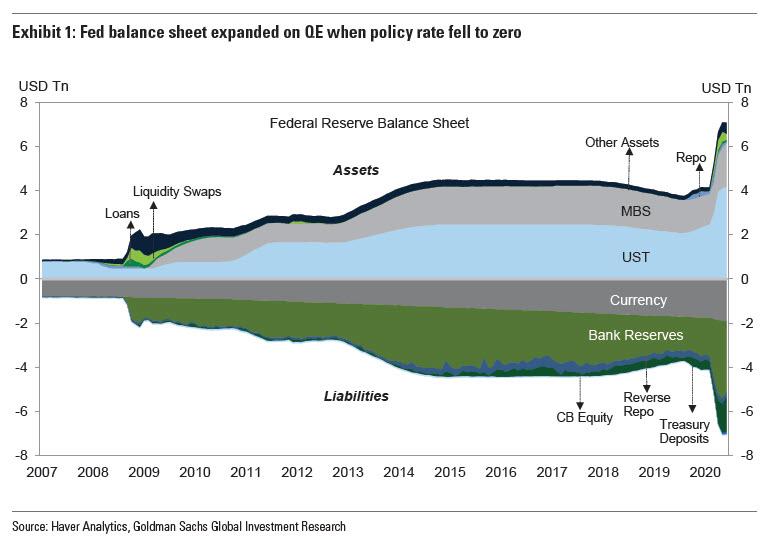

Earlier this week we discussed the striking difference between virtually every western central bank balance sheet – of which the Fed’s is a prime example – all of which have grown at a staggering pace over the past decades and especially since the covid crisis as central banks acquired various securities most notably Treasurys and MBS to ease monetary conditions…

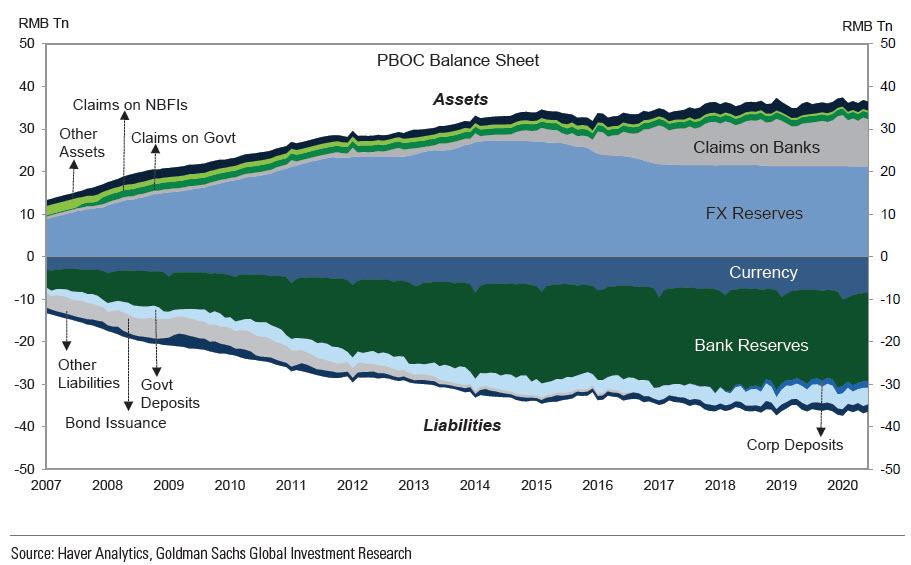

… and that of the PBOC which has been surprisingly steady because – as we explained before – China has been gradually transitioning from a quantity-based monetary policy framework to a price-based one, whereby monetary policy is primarily adjusted via quantity-based instruments such as RRR cuts.

The difference in how policies are conducted – QE purchases for the Fed and RRR cuts for the PBOC – is fundamentally the reason why we haven’t seen PBOC balance sheet behave in the same way as Fed balance sheet during the recent easing cycle.

However, the PBOC’s reluctance to engage in open and explicit QE may now be over, because according to a new report, the People’s Bank of China may have quietly bought government bonds from domestic banks in July, which as Bloomberg puts it, is a rare move that has analysts puzzling over the monetary authority’s policy intentions amid a record amount of government debt issuance.

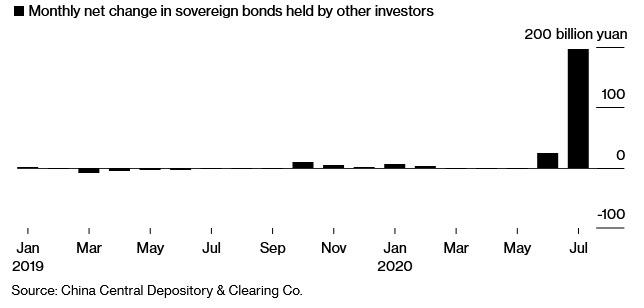

While there has been no overt change to the PBOC’s policy, tracking sovereign bonds held by “other” investors – a category that includes central banks and clearing houses – showed an increase of 196.5 billion yuan to 1.78 trillion yuan ($256 billion) last month, based on data by China Central Depository & Clearing Co.

The increase, the biggest since Bloomberg data started in late 2018, prompted analysts from Citic Securities to Nomura Holdings and GF Securities to speculate the central bank might have bought some government debt in the month.

If confirmed that the PBOC has finally joined western banks in purchasing bonds in the open market, this would be dramatic reversal to years of convention: in the past, Chinese policy makers have frequently said in the past they do not intend to enact the kind of bond-market purchases seen in developed markets and have restricted stimulus measures throughout the coronavirus crisis to moderate trimming of market interest rates and a more generous liquidity policy. But they have flagged a willingness to support the government’s fiscal policy.

Ironically, just this past May, Ma Jun, a member of the PBOC’s monetary policy committee, wrote in a newspaper article that any proposals that the PBOC should buy government debt directly would, in essence, be asking the central bank to “print money” to finance fiscal deficit.

Monetary financing “will have long-term impact on the macro economy, fiscal sustainability and financial stability,” Ma wrote in the central bank’s Financial News newspaper. Doing so would mean “giving up the last line of defense on government fiscal behavior.”

Monetary financing could cause hyperinflation, asset bubbles, currency weakening, over-borrowing and lower productivity, Ma said.

And while Ma was absolutely correct, in the end China appears to have succumbed for the temptation of CTRL-P, the same as most other central banks.

“There’s a possibility that the central bank has bought sovereign bonds,” Ming Ming, head of fixed-income research at Citic Securities in Beijing, wrote in a note, though he cited the possibility of other factors being behind the rise. The move is more likely to be an effort to “directly finance the real economy” rather than quantitative easing, with the PBOC buying anti-virus bonds that invest in projects with a steady return, he said.

Call it whatever you want Ming, at the end of the day it’s all about words and the narrative, because just like the Fed, the PBOC is forbidden by the nation’s central bank law from purchasing government debt in the primary market. That however hasn’t stopped the US central bank from monetizing $7 trillion worth of US deficits.

Researchers affiliated with China’s Ministry of Finance had previously suggested the central bank should buy some government debt this year, a step which could help reduce the impact on markets as the government plans a record amount of sales to mitigate growth risks.

None of this should come as a surprise: as Rabobank’s Michael Every sarcastically notes, “it’s not as if the Chinese state does not play a vast role in the economy and markets, is it? The consolidated fiscal deficit was already in double digits even before the virus struck according to the IMF: take a guess as to where it is now – and don’t think the PBOC isn’t ultimately backstopping this, because it is.”