Chinese ‘Robinhood’ Worth More Than Credit Suisse As COVID-19 Spurs Retail Trading Boom

Tyler Durden

Thu, 09/24/2020 – 14:55

If only the founders of Robinhood had the sense to launch in China instead of the US…maybe they could have made some real money (not that pioneering the practice of payment for order flow hasn’t been extremely lucrative).

As sports were cancelled across the US, and the world, in the spring as the coronavirus pandemic spread, retail trading has effectively replaced sports gambling for millions of young Americans who followed Barstool Sports’ Dave Portnoy headlong into the market, prompting one Fidelity mutual fund manager to complain that Robinhood is going to supplant mutual funds as the investing vehicle of choice for Americans addicted to the adrenaline rush of markets.

As the FT reported Thursday, a similar pattern played out across China, prompting discount electronic brokerage apps to see a flood of new customers and orders. The bonanza of revenue has sent shares of some of these small firms soaring. Trading volume has surged to a staggering $129 billion in daily turnover. The subsequent surge in their publicly-traded shares pushed the valuation of some of these firms past Credit Suisse (though that’s not exactly saying much right now).

As one analyst told FT “the entire sector is going crazy”.

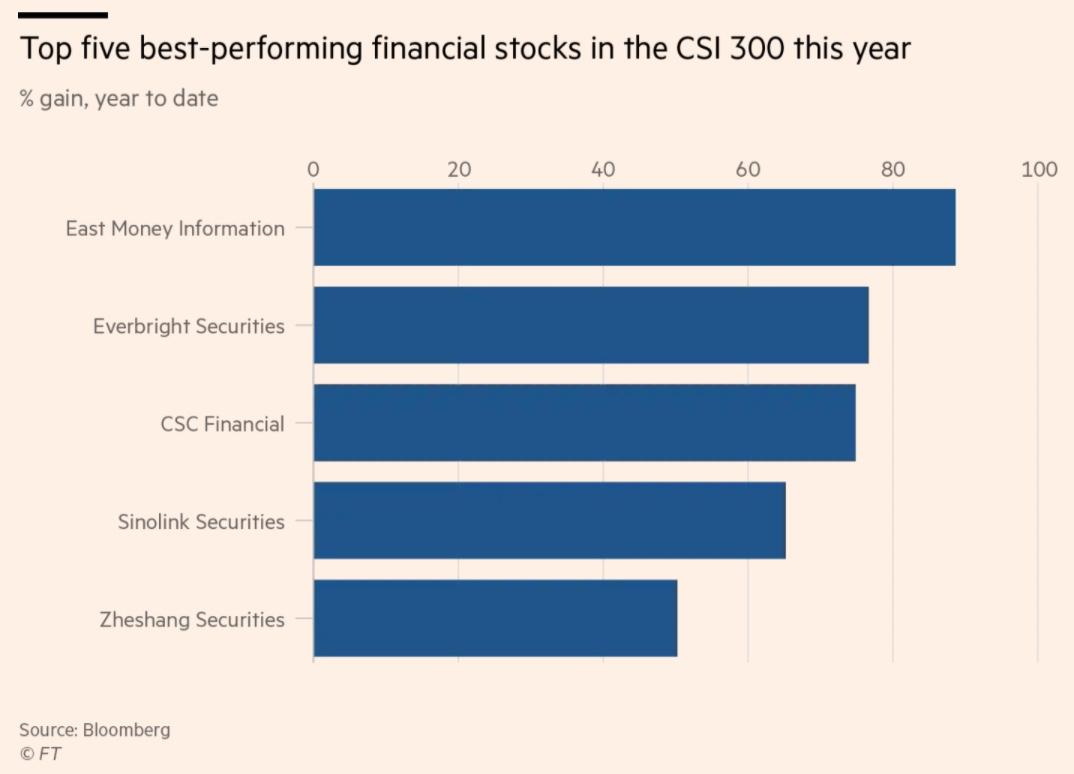

A surge in internet trading by China’s retail investors has boosted the country’s brokers, awarding some of them a valuation in line with the world’s best-known banks. Average daily turnover on China’s stock market has hit Rmb874bn ($129bn) this year, according to data from Goldman Sachs, up nearly 60 per cent from the average of the past five years, as the coronavirus crisis has driven interest in online equity trading. That has ignited shares in brokers, placing them among China’s best-performing stocks of the year. Shares in East Money, an internet trading group largely unknown outside China, have climbed by 84 per cent, giving the company a market capitalisation equivalent to $30.6bn — above that of Credit Suisse. “The entire sector is going crazy . . . all the most expensive brokerage companies are in China,” said Hao Hong, head of research and chief strategist at securities firm Bocom International. East Money shares trade at a price-to-earnings ratio of 69, compared with 14 times for US broker Charles Schwab.

Compared with the institution-dominated US market, China’s mom-and-pop traders comprise a much larger share of turnover, with the FT saying 80% of daily turnover by value is tied to retail trading.

Retail brokerages are run by a range of companies, from the relatively well known Citic Securities and CSC Financial, which have provided online services for mom and pop investors in China for several year, attracting customers with high-tech features such as facial recognition technology, to less established players.

East Money is the best-performing big financial stock in China this year. Though largely unknown outside China, its shares have climbed 84% this year, giving the company a market cap of $30.6 billion, making it more valuable than Credit Suisse.

It derives revenue from its brokerage business and commissions on mutual fund sales. The company’s revenue has increased by Rmb3.3 billion, up two-thirds, compared with last year.

Like their day-trading American counterparts, mom and pop traders in China derive so much enjoyment not just from trading, but from posting on message boards and discussing/debating their ideas with other traders. It’s this “game-ification” element that has made platforms like Robinhood, and its Chinese counterparts, so irresistible to many.

But the recent jump in turnover — prompted in part by coronavirus-related restrictions in the world’s second-biggest economy — comes with a new element: a parallel craze for mobile apps and financial platforms that allow investors to tap into market information and social networks. Liu Jianshun, a Beijing-based retail investor, said he found a “sense of belonging” from debating stock prices on East Money’s chat platform, known as Guba. He uses Guba to try to “talk up stock prices” as well as complain about poor share performance or corporate governance issues.

“East Money has created a virtual platform that replaced the physical brokerage outlets that were once the main gathering place for investors,” said a vice-chairman at one of the company’s rivals. Like elsewhere in the world — from the US to Russia — people in China have turned to the stock market at a time of rising uncertainty over other sources of income and employment due to Covid-19.

Chinese stock market turnover this year peaked in July when daily volumes exceeded Rmb1tn for 15 consecutive days, according to Goldman Sachs, as the CSI 300 index of Shanghai- and Shenzhen-listed shares reached its highest level for 2020. The benchmark is up 13.6 per cent this year.

A combination of idleness and low interest rates has helped to fuel the frenzy.

“If they still have the income, they have nowhere to spend” it, said Kinger Lau, chief China equity strategist at Goldman Sachs. “They spend more time buying stuff online and spend more time…just trading stocks at home.” Low interest rates, a problem faced by savers elsewhere in the world, have also fuelled appetite for stocks. Yu’ebao, a popular money market fund offered by Alibaba’s financial arm Ant Group, pays just over 1.6 per cent in interest. “If you look at Yu’ebao interest rates over the past few months, it’s been falling pretty steadily,” he said. “They [retail investors] are more incentivised to put money into stocks.”

Since mom-and-pop traders need companies to trade, the surge in retail trading has helped fuel a boom in Chinese IPOs, though a Trump Administration push to force Chinese companies to de-list from US exchanges unless they agree to more oversight has also contributed to this trend.

That same demand has charged China’s booming initial public offering markets. Shenzhen-listed shares of Contec Medical Systems closed up more than 1,000 per cent in its debut session last month after regulators relaxed rules on the city’s tech-focused ChiNext board.

Of course, Chinese traders are probably much more willing to throw cash at the market giving Beijing’s history of taking draconian steps like arresting short sellers if markets get turbulent. So buying stocks is like playing in casino where you really can’t lose.