Questioning Supreme Court Nominees About Religion: A Delicate Task

Tyler Durden

Sat, 09/26/2020 – 09:20

Authored by Alan Dershowitz via The Gatestone Institute,

When Judge Amy Coney Barrett came before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary for her nomination to the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, Senator Diane Feinstein generated considerable controversy when she said to Barrett:

“The dogma lives loudly in you.”

This was a reference to Barrett’s deep Catholic faith. Under our Constitution, Senator Feinstein’s statement crossed the line. Ours was the first Constitution in history to provide that “no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.”

Although Feinstein did not explicitly impose a religious test, she suggested that personal religious views — which she called dogma — might disqualify a nominee from being confirmed.

That would clearly be unconstitutional.

When Justice Louis Brandeis was nominated to the United States Supreme Court in 1916, numerous leaders of the bar and prominent Americans, including the president of Harvard, opposed his nomination, sometimes implicitly, sometimes explicitly, on the ground that he was Jewish. That was wrong then, and it is equally wrong today with regard to a nominee of the Catholic faith.

Indeed, today’s Supreme Court has five justices who are Catholic, two who are Jewish, and one who is Protestant. Religious tests have no place in America. But what does have a place in the confirmation process are questions about whether a nominee will put faith before the Constitution and refuse to apply the Constitution if it conflicts with his or her faith. That issue would be true of any nominee regardless of their faith or faithlessness. President John F. Kennedy assured us that his Catholicism would not determine the nation’s policy. Justice Antonin Scalia said the same about his Catholicism and his jurisprudence.

It is impossible, of course, to psychoanalyze a nominee or justice to determine what role if any their faith may play in their jurisprudence. We are all influenced by our personal views, including but not limited to religious views. When Justice Pierce Butler issued the sole dissent in the notorious case of Buck v. Bell — in which the Supreme Court, led by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, permitted the sterilization of supposed “mental defectives” — many speculated that his dissent, which is now seen by most historians and lawyers as the correct view, may have been motivated consciously or unconsciously by his deep Catholic faith. The Catholic Church was inalterably opposed to sterilization of the mentally disabled, whereas the “progressive view,” centered at Harvard University, strongly favored such “eugenic” procedures to “improve” the “race.” The church was right and Harvard was wrong on this one, and it was a good thing that there was a religious Catholic on the high court to register a dissent to what we have now come to believe was an outrageous violation of human rights.

The role of religion in judicial decision-making is complex, nuanced and sometimes difficult to discuss. There is no sharp line between ideology and jurisprudence, but a line must be drawn nonetheless, especially when questioning a candidate for the Supreme Court.

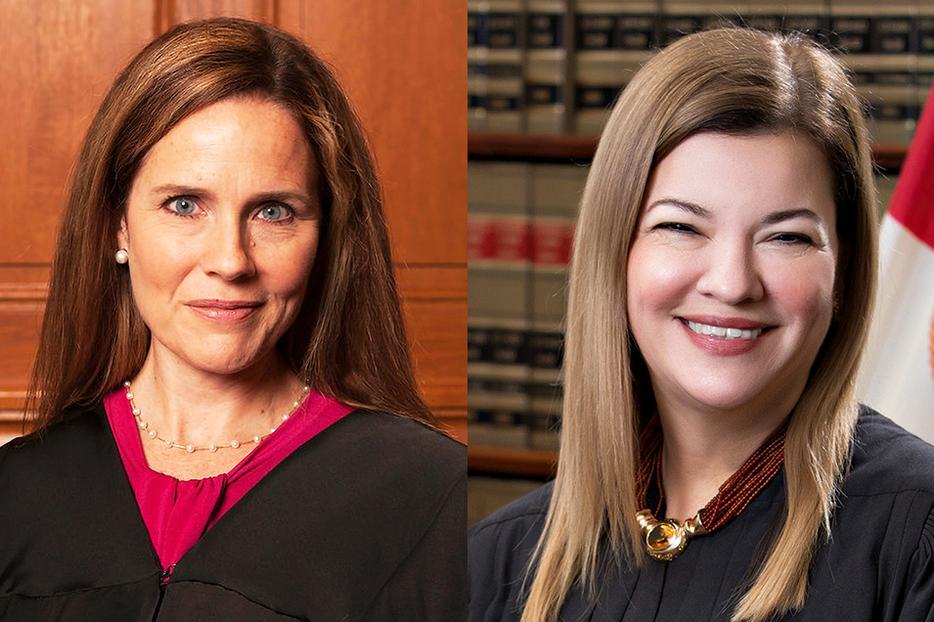

Judge Amy Coney Barrett is now the leading candidate, followed by Judge Barbara Lagoa, who is also a deeply religious Catholic woman of Cuban American background. So, the issue of religion is likely to come up at any confirmation hearing. It must be handled with delicacy and sensitivity to the Constitution’s prohibition against religious tests, as well as to the respect we must all pay to people of faith.

Several years ago, a United States Senator declared that he would never vote to confirm an atheist to the Supreme Court. Such a position is in direct conflict with the Constitution. But because questions about religion are generally not asked of candidates, it is highly likely that several atheists and agnostics have served on the high court. Oliver Wendell Holmes publicly acknowledged his disbelief in religion and several other justices have privately acknowledged their lack of religious faith. One’s religion is a private matter, but one’s judicial philosophy is highly relevant in the confirmation process.

The confirmation process has become so politicized, so personal, and often so unfair, that it is especially important to draw careful distinctions with regard to religious beliefs and observance. Let us hope the Senate handles this nomination better than they have handled other recent nominations.