“It’s A Civil War”: Decade Of Covenant-Lite Deals Leads To Leveraged Loan “Panic”

Tyler Durden

Wed, 10/07/2020 – 20:00

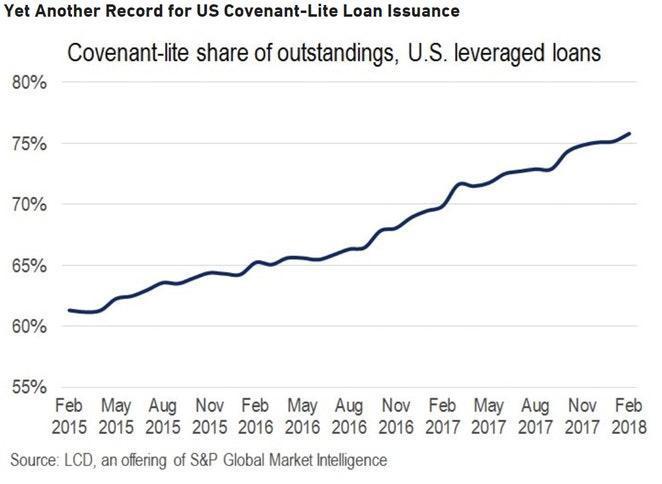

It was a little over two years ago that we last looked at the “covenant lite” insanity sweeping the loan market for the past decade, where as a result of a buying frenzy among yield-starved investors, corporations had managed to get away with selling “secured” debt that was anything but secured, and offered only the slimmest – if any – protections to investors. In fact, by early 2018, the amount of covenant-lite loans hit an unprecedented 75%…

… which meant that Moody’s Loan Covenant Quality Indicator (LCQI) dropped to its record-worst level in the first quarter of 2018.

“While the rate of deterioration in covenant quality has slowed, protections remain distressingly weak on average,” said Derek Gluckman, Moody’s VP-Senior Covenant Officer. “Investors should remain wary given the risks presented by most loan documents and the likelihood that any steadying of covenant protections is temporary.”

But it wasn’t just the sheer volume of cov-lite outstandings that mattered: an analysis by LCD looked at the debt cushion of outstanding loans – the amount of debt in a borrower’s capital structure that is subordinated to the senior loan – and found that most cov-lite deals have little or no debt cushion beneath them. Consider that by mid-2018, an all time high 23% of all cov-lite loans did not have any debt, such as a mezzanine tranche, high yield bond, or other, below the cov-lite facility. That number was up from 18% in 2013 and from just 10% at the end of 2007, shortly before the financial crisis.

This is also why we explicitly warned that “the lack of a debt cushion significantly lessens what an investor will recover on a loan, if that credit defaults” and left readers with the following:

In other words, during the next default cycle, whenever the business cycle finally turns, loan investors not only will have virtually no “secured” protection, but are now the de facto equity tranche in numerous deals, or said otherwise, for the first time in history, loan investors are looking at 0 recoveries in default.

Well, fast forward to today when the chickens from the covenant-lite euphoria of the past decade have come home… for the slaughter.

In a transaction which has terminally tilted the “landscape in favor of distressed borrowers and pitted creditors against each other” a $120 million loan to cash-strapped restaurant supplier TriMark USA has “not only unilaterally placed the new lenders above everyone else in the repayment pecking order, but it also stripped some of the older creditors of safeguards they had written into the contracts to protect their investments” according to Bloomberg, which notes that when word of the deal spearheaded by Howard Marks and his distressed debt giant, Oaktree, first hit the market in mid-September, “it sparked a panic“, prompting investors to puke the old loan so fast it cratered 20 cents in days, an unheard of move in the world of secured finance where underlying assets never reprice so fast, even in bankruptcy.

Of course, for those who had been following the degradation of creditor protections and the ascent of cov-lite deals over the past decade, what just took place is hardly a surprise: as investors bargained away most of their legal rights in hopes of getting a modest allocation in the latest “high yielding” note, they now find themselves with virtually no protection for their investments just as the pandemic is causing a wave of corporate bankruptcies across the country.

And just to underscore that “anything goes” in the brave new world of leveraged (and unsecured) loans, the presence of Marks – who had long been seen as one of the more staid voices in a distressed-debt world full of pugnacious vultures – served to upend the market only further and spark fears about what is coming next as tens of billions of other “secured” loans are about to see their investors crammed down or otherwise wiped out, just as we warned in 2018.

“It’s a civil war between lenders, and we’re going to see more of this,” said Thomas Majewski, managing partner and founder at Eagle Point Credit Management. “Nearly every company restructuring debt is looking at these possibilities.”

So what exactly happened?

The TriMark transaction, which according to Bloomberg was similar to another loan that surf-clothing maker Boardriders entered recently, followed in the “priming” footsteps of a divisive financing by Serta Simmons Bedding earlier this year. The mattress maker got $200 million of fresh capital from existing lenders including Eaton Vance Corp. and Invesco Ltd. Those lenders jumped to the top of the capital stack meaning they would be repaid first if the company defaulted, pushing Serta Simmons’ other lenders further back, in a process known as priming.

There’s nothing new about priming – in fact it happens all the time in bankruptcy when a company issues what is known as a “priming DIP” – but the way lenders did it in the Serta Simmons deal resulted in litigation. The new investor group led by Eaton Vance and Invesco didn’t give all other lenders the right to participate in the new loan, a move that is allowed by many deals’ documents, but hadn’t really been done before. Lenders who were left out, including Apollo Global Management, sued the company but a state court let the deal go ahead, ushering in a new precedent in the market where existing “secured” creditors hiding behind the thin defense of non-existent covenants, realize they are in fact, unsecured.

“Serta did open the floodgates in that regard,” said Tim Sullivan, an analyst at Xtract Research, “because it showed how provisions which are very common in agreements today can be used to incur priming debt.”

Of course, creditors have only themselves to fault: nobody put a gun to their heads in 2010-2018 when they signed the dotted line on yet another high-yielding loan that offered no covenant protection. Yet they just had to do it. Well, now that the catastrophic event that nobody thought could possibly happen happened, and as investors pore through their covenant term sheets, they finally realize why all those warnings over the past decade hit home.

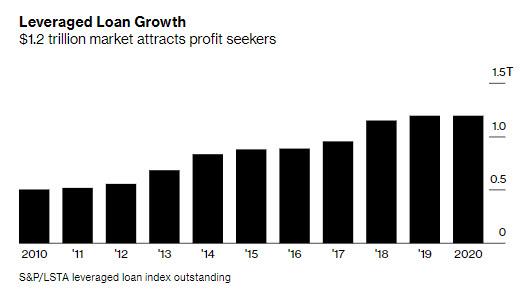

The catalyst for this realization, of course, is the covid crisis, as a result of which countless companies in the U.S. are going broke as the pandemic saps their revenues. Fitch Ratings projects 7% to 8% of leveraged loans will default by the end of 2021, compared with 1.8% in 2019, a cataclysmic event for the $1.2 trillion loan market. Making matters worse, after years of the loan market growing rapidly, failing corporations that issued debt and pledged assets now have less in the way of income or assets to fork over to creditors, which is making fights among all parties more acrimonious.

It also means that those investors with fresh capital can trample over the gullible ones who received a couple of years of interest payments and are now facing near complete losses on principal.

In the case of Boardriders, Oaktree was one of the equity owners: as Bloomberg details, the company negotiated a $135 million financing including a $45 million loan that has priority over all others. The debt came from Boardriders’ bigger lenders, a group that included Brigade Capital Management, Canyon Capital and MidOcean Credit Partners, according to people with knowledge of the situation.

The $45 million loan, which is effectively a pre-petition DIP, ranks ahead of all investors that didn’t participate in the new financing. Just as a secured bankruptcy loan does. The minority lenders that were primed argue that was unfair because they weren’t given a chance to participate in the deal, the people said. Good luck to them: meanwhile, the new loan which is secured by all the assets, is trading around 100 cents on the dollar; the old loan that was primed? About a third of that, or around 35 cents.

The situation was similar for TriMark. The company saw its revenue falling and hired advisers to help it consider its options. It ultimately picked a transaction to raise $120 million from lenders including Oaktree and Ares Management Corp. The group of existing lenders also included Blackstone’s credit arm GSO Capital Partners, Sculptor Capital Management, and BlackRock. Their new loan is trading around face value, about 40 cents on the dollar higher than the loan that was primed. TriMark is owned by Centerbridge, which is about to get a big fat doughnut on its investment.

So how did the new investors prime existing lenders? In both Boardriders and TriMark, minority lenders had covenants including limits on future company borrowings removed, while the debt amortization schedule was slowed down.

According to Etract’s Sullivan, the additional step of removing covenants is highly unusual in the loan world and is a big loss for investors. On the other hand, such covenant stripping would never had been possible if the loans were not covenant-lite to begin with.

“It’s gone beyond Serta — now it’s worse. By stripping it down to the ultra bare bones, all that leaves you with is just a promise to pay,” he said.

It also means that the entire $1.2 trillion universe of secured loans – because by definition first and second-lien bank debt is secured by company assets and has first dibs on them in case of default – is effectively no longer secured.

* * *

To be sure the primed lenders are fighting back, and some companies are deciding not to embrace these transactions (they can of course do that, but one way or another a priming loan will come, the only difference is that if it is in bankruptcy, it is called a DIP Loan). Meanwhile, covenant lite deals have resulted in even more ingenious instances of asset stripping. In May debtholders rebelled against Elliott Management and Siris Capital Group, the owners of global travel reservation company Travelport, after those two firms tried to move assets out of the reach of creditors. And when Oaktree proposed a priming transaction for PSAV, the borrower elected to raise new capital through a loan that was in the same class as the existing facility.

“Priming transactions such as those executed by Serta and Boardriders are still the exception and the priming play is not the ‘new normal,’” said Judah Gross, a director at Fitch Ratings. “That being said, the higher degree of frequency with which such deals get done may indicate that priming transactions are not as taboo as once assumed.”

He is right, and the real kicker will take place some time in 2021 if there is no new fiscal stimulus, and a default wave washes over the leveraged loan market: only then will our warning from 2018 become clear – years of issuance of loans that were “secured” only in name, has ensured that recoveries for these unsecured creditors will be the lowest in history; in fact depending on the severity of the coming double dip, it is likely that “secured” lenders are looking at the unthinkable – a total wipeout on principal.