Deflation Is Back In China As CPI Turns Negative For First Time Since The Financial Crisis

Tyler Durden

Tue, 12/08/2020 – 22:50

Yesterday, when discussing the biggest jump in Chinese FX reserves in 7 years we wondered if this was an indication that the PBOC was starting to lean against the surging yuan. Today, after the latest Chinese inflation data released moments ago, we are confident that it is only a matter of time before Beijing will once again aggressively intervene and/or devalue its currency.

According to the National Bureau Of Statistics, in November China’s CPI unexpectedly tumbled to -0.5% Y/Y in November, below market expectations and the first year-over-year decline in consumer prices since the financial crisis. While rapid decline of food prices continued to be the main driver for lower headline CPI inflation, non-food inflation also edged down to -0.1% yoy from 0% yoy in October, which begs the question: how much of China’s now deflation is the result of the surging yuan, and how much longer will Beijing tolerate the soaring currency (or, said otherwise, the plunging dollar). On the flip side, PPI inflation was at -1.5% yoy in November, which while still negative (the last positive PPI print was in January), was less negative than October as inflationary pressures increased along with the strong expansion of industrial activity.

Here are the key numbers:

- CPI: -0.5% yoy in November, exp. +0.0%; down from October’s +0.5% yoy.

- Food CPI: -2% yoy in November; October: +2.2% yoy.

- Non-food CPI: -0.1% yoy in November; October: +0.0% yoy.

- PPI: -1.5% yoy in November. exp. -1.8% yoy; up from October’s -2.1% yoy.

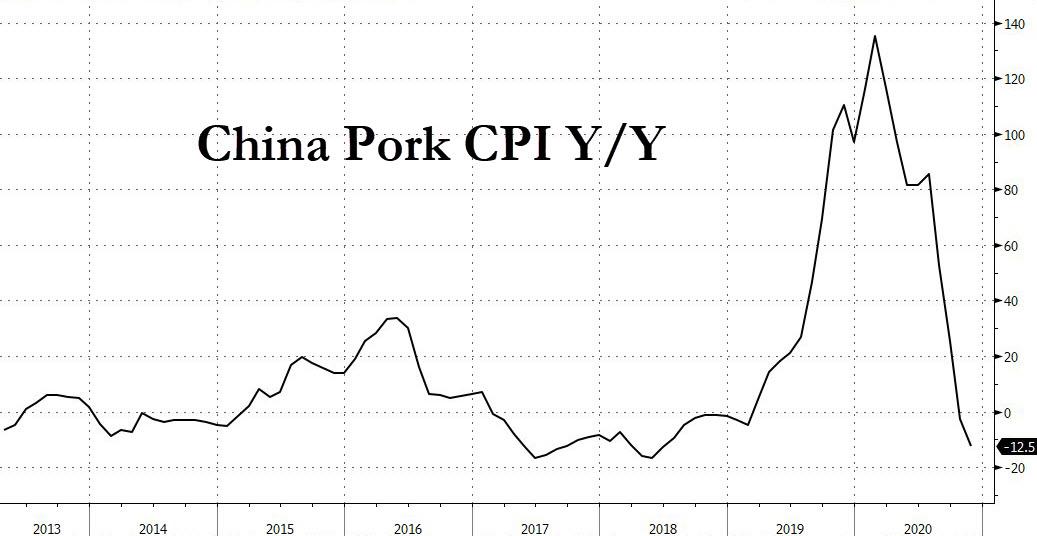

Some more details: in year-on-year terms, food inflation went down to -2.0% yoy in November from +2.2% yoy in October, largely because pork prices tumbled 12.5% on a year-over-year basis, lowering year-over-year CPI inflation by 0.6pp.

Egg prices also plunged, dropping 17.1% yoy, and lowering the headline CPI by another 0.1pp. Fresh vegetable prices rose albeit at a slower pace: Inflation in fresh vegetables was +8.6% yoy in November (vs 16.7% yoy in October), adding 0.2pp to headline CPI inflation.

Non-food CPI inflation edged down to -0.1% yoy in November, from 0.0% in October. Fuel costs fell further by 17.6% yoy, vs -17.2% yoy in October. Core inflation (headline CPI excluding food and energy) was unchanged at +0.5% yoy in November.

On the other side, PPI inflation rose modestly and was at -1.5% Y/Y in November, less negative than October. In month-over-month annualized terms, PPI rose by 5.6%, vs -1% in October. Price declines narrowed for producer goods (-1.8% yoy vs -2.7% yoy in October) but price decline for consumer goods widened (-0.8% yoy in November, vs -0.5% yoy in October) mainly on lower food and clothing price inflation. By major industry, PPI inflation increased on a year-over-year basis in most sub-industries except food processing and telecom industries.

According to Goldman, headline CPI inflation may remain at low levels in the coming months on falling food prices and a high base while PPI inflation could rise further as inflationary pressures continue to build in the industrial sector.

A bigger problem for China is that while PPI may be rising, it’s only a function of higher commodity prices and industrial strength on the back of massive credit injections; meanwhile consumer deflation is starting to emerge as a major concern for a country that has not had a negative CPI print since 2009.

One wonders how long Beijing will allow this, and how long will Chinese rates remain as high as they are, before the Politburo capitulates and realize it needs to aggressively devalued its soaring currency (and offset the tumbling dollar) if it hopes to keep deflation in check.

It may even have to decide between keeping interest rates highs, and thus yields on Chinese bonds attractive for foreign investors (as a reminder, everyone knows by now that one of Beijing’s top priorities is to have a steady source of offshore capital entering the negative current account nation), or finally conceding it needs to cut rates in order to let some of the air in the yuan out.