Inflation, Deflation, & Other Fallacies

Tyler Durden

Sat, 09/12/2020 – 07:00

Authored by Alasdair Macleod via GoldMoney.com,

There can be little doubt that macroeconomic policies are failing around the world. The fallacies being exposed are so entrenched that there are bound to be twists and turns yet to come.

This article explains the fallacies behind inflation, deflation, economic performance and interest rates. They arise from the modern states’ overriding determination to access the wealth of its electorate instead of being driven by a genuine and considered concern for its welfare. Monetary inflation, which has become runaway, transfers wealth to the state from producers and consumers, and is about to accelerate. Everything about macroeconomics is now with that single economically destructive objective in mind.

Falling prices, the outcome of commercial competition and sound money are more aligned with the interests of ordinary people, but that is so derided by neo-Keynesians that today almost without exception everyone believes in inflationism.

And finally, we conclude that the escape from failing fiat will lead to rising nominal interest rates, with all the consequences which that entails. The inevitable outcome is a flight to commodities, including gold and silver, despite rising interest rates for fiat money.

Demand-siders and supply-siders

In a macroeconomics-driven world, economic fallacies abound. They are periodically trashed when disproved, only to arise again as received wisdom for a new generation of macroeconomists determined to justify their statist beliefs. The most egregious of these is that inflation can only occur as the handmaiden of economic growth, while deflation is similarly linked to a recession spinning out of control into the maelstrom of a slump.

This error is the opposite of the facts.

Conventionally, macroeconomists split into two groups. There are the Keynesians who believe in stimulating demand to ensure there will always be markets for goods and services, which they attempt to achieve through additional spending by governments and by discouraging saving, because it is consumption deferred. And there are the supply-siders, who believe in stimulating production through lower corporate taxes and lighter regulation. Both demand and supply-siders advocate monetary inflation in the belief that their methods stimulate an economy so that government spending need not be cut.

The maintenance of government spending is the objective of both approaches, not the welfare of economic actors, who are always regarded as the state’s milch cows. While supply-side reforms have proved more attractive to free traders than Keynesian demand stimulus, the end result is the same: the combination of taxes and monetary seigniorage from the productive economy transferred to the state is the objective either way.

The smoke and mirrors to get people to part with their wealth are the misuse of statistics. The price consequences of monetary inflation are suppressed by statistical method, and economic growth is substituted for economic progress, the combination leading to confusion for nearly all economists. But the facts behind the measure of growth, gross domestic product, are easily explained.

First, the modelling assumptions. As a starting point we must assume there is no inflation of money and credit and the quantity of money is fixed. That being the case, and assuming no change in the statistical make-up of GDP, nor in the quantity of hoarded cash, and assuming no change in the balance of external trade, there can be no increase in nominal GDP, because whatever people make, sell and consume amounts to the same total expressed in money terms compared with the previous period. It is an accounting identity. Whether savings increase or decrease is immaterial, because GDP is the total of final goods and intermediate goods, so if an economy evolves from being consumer to savings driven or vice-versa, GDP must remain unchanged. The split between profit and costs is immaterial as well, the sum of the two being contained within the GDP total. But variations in the rate of economic progress will always be reflected in the individual prices and quantities of goods and services produced without the total monetary value of all transactions changing. A progressive economy will see more and better goods and services at lower prices, while for a failing economy the opposite is be true.

The next step should not be beyond the understanding of anyone. If a fairy godmother magically created some extra money for the people in an economy to spend, it must simply be added to the GDP total, whether they spend it or save it — as long as they don’t hoard it. Saving circulates, because it is money made available for investment. Hoarding is taking money out of circulation, which is why in our model we must assume the quantity of money hoarded does not change.

Macroeconomists confuse the additional money injected into the economy with growth. It is growth in the money total only, because it is impossible to judge the degree to which it is used to economic advantage. Economic growth has become confused with economic progress. Economists today appear unaware of this distinction, which Ludwig von Mises separated out into what he called an evenly rotating economy. He defined it as follows:

“An imaginary economy in which all transactions and physical conditions are repeated without change in each similar cycle of time. Everything is imagined to continue exactly as before, including all human ideas and goals. Under such fictitious constant repetitive conditions there can be no net change in any supply of demand and therefore there cannot be any change in prices.”

The inconvenient truth for statists is that with GDP they can only measure the quantity of money in total transactions, not how it is used. This fits von Mises’s description of an imaginary economy that evenly rotates and it is vital for any student of economics to understand this point. It matters not whether he or she is a demand or supply-sider; both categories of macroeconomic emphasis wrongly believe in targets for GDP outcomes, which are meaningless except for the purpose of maintaining government revenue. And that is the key to their interest.

It is with this perspective that we must understand the role of monetary inflation in an economy, and the reason for underlying, statist-driven beliefs that inflation is good, and deflation is bad. For the state the absence of monetary inflation is a loss of a growing and important source of revenue at a time of escalating welfare and other costs.

Coronavirus shutdowns have thrown the problems facing government finances into sharp relief. Keynesians are yet again losing the practical argument as all nations see government finances spinning out of control. Instead, the policies behind governments’ finances have been forced to drift into a default version of supply-side economics to help businesses survive. Taxes on businesses have been deferred or cut, employment subsidised, and the rich left alone. If anything, the rich are being subsidised through asset price inflation, which is the initial consequence of accelerating monetary inflation.

Whether it is demand or supply being manipulated, the one objective behind it all is the satisfaction of government finances over the business cycle.

Economic progress is reflected by falling, not rising prices

Now that hopefully we have put the GDP fallacy in its proper context, we are in a better position to understand why, contrary to modern economic doctrines, the natural state for an economy that progresses is not one that sees continual and planned inflation, which are monetary policy objectives, but gradually falling prices. This was the experience under the gold standard of the nineteenth century and is easily explained: within a confined money total such as that of monetary gold, an increase in the quantity of goods and services taking place can only be accommodated by a decline in the general level of prices. Put another way, the purchasing power of sound money, a money whose quantity is not inflated, always rises over time.

Not that the quantity of gold and gold substitutes was ever fixed. In the nineteenth century, the quantity of monetary gold was inflated by new discoveries in California, Australia and South Africa, and we must also mention the fluctuations in bank credit which masqueraded as gold substitutes. But the expansion in the money quantity was insufficient to prevent the general level of prices falling over time between the introduction of the gold standard in Britain in 1821 and the First World War. And it should go without saying that it was this period that saw the bulk of the British population move from bare subsistence living to immensely improved conditions.

Today’s macroeconomic beliefs defy all the historical evidence with its focus on increasing the economic presence of the state at the expense of the productive private sector. Free markets and sound money benefit savers and workers by increasing the purchasing power of their savings and wages over time. They encourage the accumulation of personal wealth. They displace the speculation predominant in financial assets today. They discourage profligacy, indolence and needless borrowing. With the exception of the destitute and others who can be more effectively supported by voluntary institutions, they allow the vast majority of people to provide for their own personal health and retirement, freeing their governments from onerous welfare obligations.

In other words, the mild but continuous deflation of prices, which is the principal feature of sound money, removes a financial burden from the state, leaving it with minimal negative economic impact. And the smaller the government is, the less its tax depredations are on economic actors and the more effectively the free market economy becomes in improving standards of living for all.

By comparison, today’s unsound money conditions are inherently destructive. Monetary inflation indiscriminately robs both savers and wage earners. Not only is the accumulation of personal wealth by the masses taxed away or discouraged, speculation in financial assets is encouraged in order to create a replacement wealth effect. Profligacy, indolence and needless borrowing are hallmarks of the inflationary regime. Companies lobby for subsidies and for government protection from competition by creating anti-competitive regulatory burdens to discourage upstart innovators. Nearly everyone can freeload on state-provided welfare, the provision of health and mandated minimum wages. Government’s non-productive burden on the economy inevitably grows to the point of economic strangulation.

It follows that the progressive wealth transfer from its citizens into the government’s hands through monetary inflation reduces not only the value of wealth left to be transferred but as noted above it becomes an increasing burden on the economy. Insofar as the government has mandated to itself future liabilities, in inflationary times those liabilities also rise in their estimated net present value making them unaffordable, even though it is naively claimed that inflation benefits government finances by reducing the value of its existing debt. The final outcome of inflationary financing is always the same: the destruction of the productive economy through increasing wealth transfer and therefore of the currency itself.

Due in part to the coronavirus, now that economies are visibly sliding into an economic abyss the end is in sight for macroeconomic fallacies. But in the coming months we will have to endure a doubling down of destructive monetary policies as Keynesians and supply siders battle it out over how to access and deploy the citizens’ remaining wealth. The true scale of their mistakes will only be revealed in a final crisis and the end of fiat currencies.

Interest rates

Part of the Keynesian myth is that businesses are forced to pay unnecessarily high interest rates by avaricious savers. Keynes argued that by replacing savers with the state as the provider of monetary capital, a far lower rate of interest can be applied, encouraging production. Keynes’s dream of euthanising the rentier class was to be accompanied by the state limiting the entrepreneur’s profits: those “…who are so fond of their craft that their labour could be obtained far cheaper than at present”.

From these objectives we learn that Keynes’s misunderstanding of the economic role of interest rates and of borrowers and lenders are derived from his socialist bias. The truth is that interest rates reflect the difference between possession of goods and their possession at a later date — their time preference. Savers view the matter differently from borrowers. To a saver, departing with possession of his money, which represents the range of goods and services he might otherwise acquire with it, is purely a matter of time preference incorporating factors to reflect the specific risk of lending to a particular borrower and of the purpose to which the loan is put. For the businessman it is less a matter of time preference and more a matter of business calculation.

It is also a common error to think it is greedy savers who set interest rates higher than they need otherwise be. In a free market, it is businesses in their economic calculations which establish the level of interest rates, bidding up for savers’ savings to a commercially feasible level; savers generally being reluctant to defer their consumption without good reason.

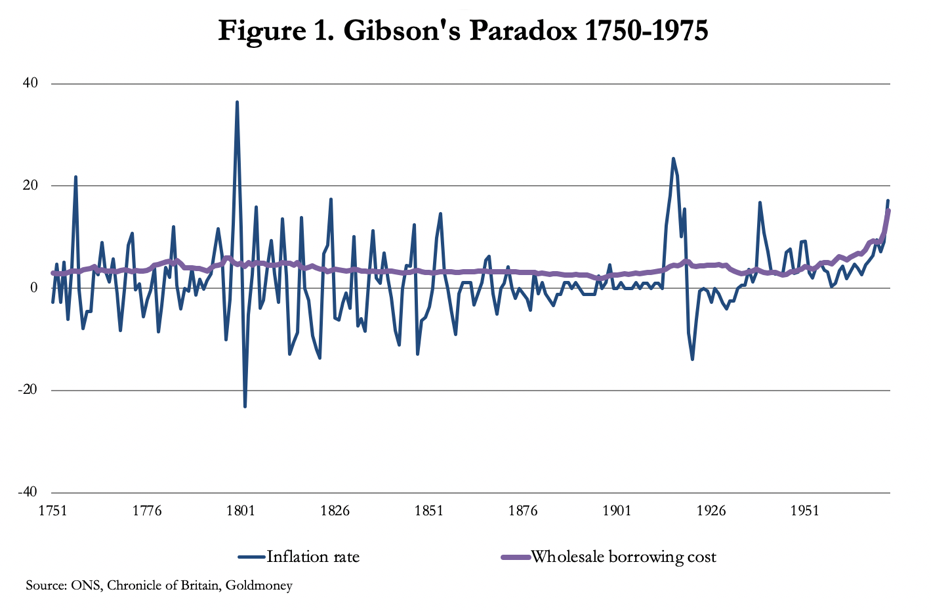

This, at least, is the lesson from the resolution of Gibson’s paradox, the explanation of which defied macroeconomists from Fisher to Keynes. Ignoring Gibson’s paradox, simply because it could not be explained, turns out to be a mistake of the greatest magnitude, because its resolution confirms empirical evidence of the paradox, that there is no correlation between short-term interest rates and the general level of prices. Consequently, interest rate policies cannot achieve their stated objectives. This lack of correlation is shown in Figure 1, when over 245 years, even violent swings between inflation and deflation in Britain through wars and slumps failed to disrupt the relationship between wholesale borrowing costs and the general level of prices. The only exception in all that time was in the run up to the gold pool failure in the late sixties and after President Nixon discarded the last vestiges of sound money by ending the Bretton Woods agreement in 1970. That period saw the increasing dominance of unsound money, which in subsequent decades increasingly subverted the relationship through a combination of statist suppression of both interest rates and the general level of prices. In other words, the evidence became buried.

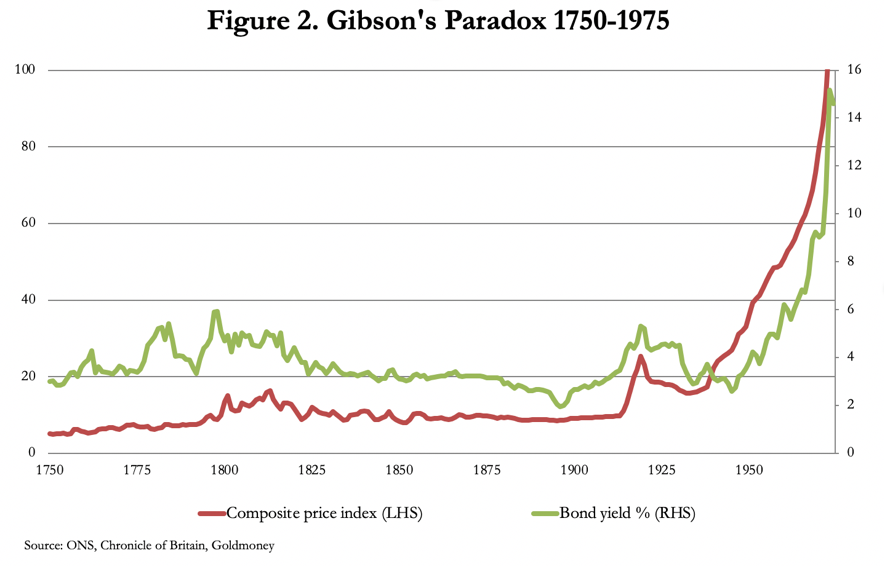

Instead, wholesale borrowing costs correlated with the general level of prices, as shown in Figure 2. Note how the correlation remained intact in the early days of purely fiat money, both rising together with important implications for today. The explanation is that in a market-driven economy business calculation is tied to prices for final products, and it is therefore those expectations that set borrowing costs. We have more to say about the implications of Gibson’s paradox later in this article.

That does not stop macroeconomists from pursuing their cherished interest rate myth. The unanimous opinion today is that interest rates must not be permitted to rise. For example, the currently strong euro is taken to threaten intensifying deflation in the Eurozone which, they say, can only be cured by deeper negative interest rates. But as we have seen, deflation is not the problem the inflationists would have us believe. They are confusing their macroeconomic theories with the economic distortions accumulated over the decades due to their erroneous monetary policies.

With macroeconomic policies proceeding in the wrong direction those distortions will finally unwind of their own accord — most likely in dramatic fashion. The obvious breaking point is between the time preference of current possession relative to future ownership, and its tension with official interest rate policy in a rapidly inflating currency. We must comment briefly on how this will be resolved.

Ordinary people in countries like America and Britain are no longer the major depositors at the banks or owners of fixed-interest bonds. Bank liabilities are dominated by business entities, much of it purely financial, which have accumulated the bulk of deposits in the banking system as well as in short-term money instruments. And in the US, over $6 trillion of bills and bank deposits are owned by and due to foot-loose foreign governments and corporations through the correspondent banking system.

These depositors are more sophisticated than small savers and will not hesitate to reduce their balances if the currency’s purchasing power declines. For the moment there is an uneasiness, with interest rates at the zero bound, and negative in the Eurozone, Japan, Switzerland and Denmark, all in defiance of time preference. These are everywhere suppressed interest rates, failing to stimulate a recovery, Keynesian or otherwise. But when the gaol-sought inflation rate of 2% is no longer believed, the central banks will have to raise interest rates or face a rapid collapse in their currencies’ purchasing power. And it is here that an additional muddle needs to be resolved.

Why price inflation increases in a failing economy

In macroeconomic theory, there are only two conditions. There is one of inflationary prices, driven by demand, a condition that leads to full employment. The second is one of deflationary prices and rising unemployment. Rising prices and unemployment together are deemed an oddity by macroeconomists. But in formulating their beliefs they ignore the evidence. Every inflation impoverishes ordinary people, as pointed out earlier in this article, and instead, falling prices are a boon to them. Furthermore, other than a temporary boost to an economy from inflation, if it transpires at all, the normal condition is for inflation and rising unemployment to go together, unemployment being the consequence of wealth transfer.

Furthermore, we can easily explain what has become to be described as stagflation — the combination of a stagnating economy and rising prices. Humans specialise in their production to maximise their output so that they can satisfy their needs and wants. Money is just the intermediary commodity which facilitates turning their production into their consumption. It follows that if producers are not buying, it is because they are not producing, so we can dismiss the idea that falling consumption leads to excess supply and lower prices. Therefore, the contraction of demand broadly matches the contraction of supply in a stagnating economy.

That leads us to consider the price effect of increasing the quantity of money in a stagnant economy, or one that contracts in terms of goods and services exchanged. We now have a condition of more money chasing fewer goods with a predictable result.

It compares starkly with a condition of economic progress, whereby expanding activity is driven by market competition. This is because the falling prices for products that are the consequence of competitive markets counters the price inflation effect from increases in money and credit. As we sink therefore into a production and consumption crisis, the general level of prices will rise sharply on the continuation of current monetary policies as the competitive effect on prices diminishes.

In the next few months, when monetary planners find this out for themselves, further monetary inflation will be increasingly untenable policy. Furthermore, interest rate reductions as the Keynesian solution to rising unemployment can be ruled out. Monetary authorities will be forced to navigate between two objectives: will it be more monetary inflation to finance the government’s rocketing deficit, contain unemployment and let the currency go hang, or higher interest rates in an attempt to protect the currency, whatever the cost to government finances?

Interest rates must rise but gold and silver will be unstoppable

While monetary authorities are contemplating their options, the decision will not be in their hands. With some $27 trillion in foreign securities and the aforementioned dollar deposits, the dollar is particularly vulnerable to liquidation by foreigners, and as foreigners start repatriating funds to their home currencies — a process that’s hardly started — it won’t be long before markets begin to discount rising dollar interest rates, thereby undermining financial asset values around the world. It will be a trend resisted strongly by the authorities, but once they are on the run from market forces there will be no macroeconomic option between raising interest rates and seeing the currency collapse.

This will lead to the last test of macroeconomic fallacies, and that is the gold price, hovering in the wings ready to replace fiat money, always falls when interest rates rise. The logic is that when interest rates rise it is more expensive to hold gold, which just sits there not earning anything. And since markets discount future expectations, gold will even fall when a rise in interest rates is only expected.

The conditions where this has been a predictable outcome have been during recent decades, characterised by central banks having control over interest rates while government statisticians manipulate the statistics upon which mathematical macroeconomists rely for their analysis. Otherwise, at times of accelerating monetary inflation and of the state losing control over markets, it is a myth, disproved by empirical evidence which can be fully explained.

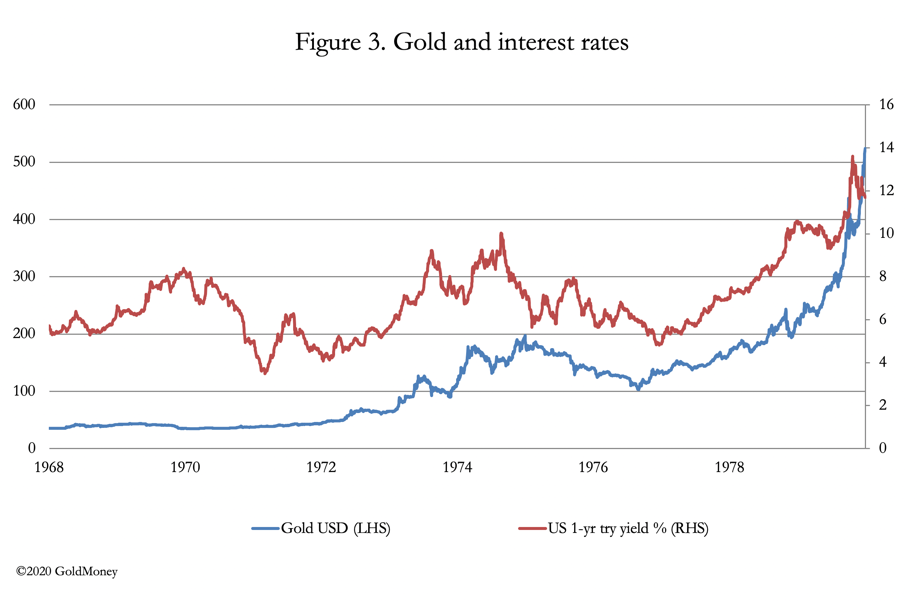

Figure 3 below is of a time when the opposite of the current understanding was demonstrably true. From 1971 to 1979 the directional trends in both interest rates and the gold price rose and fell at almost the same time. It is worth noting that this occurred over more than one business cycle, so it is not a relationship which was cycle-dependant.

Central banks in the post-Bretton Woods environment had lost control of interest rates to markets. Based on empirical evidence the myth is therefore satisfactorily addressed. To understand why this relationship between interest rates and gold is not as simple as commonly believed, we must take the argument further to bring in commodities generally and revisit the tricky subject of Gibson’s paradox. This paradox (see Figure 2) is based on long-run historical evidence, when silver or gold were transaction money (except for the last decade), covering the 245 years between 1730 and 1975. It observes that the level of wholesale prices and interest rates are positively correlated. The common view in markets today about the relationship between interest rates and price inflation is therefore wholly at odds with the longer-run evidence of Gibson’s Paradox and accords with the more fashionable theory that interest rates can regulate the quantity of money and therefore the rate of price inflation instead.

Those who centrally plan our money and markets appear unaware of the challenge the paradox poses to their preconceptions. Keynes, no less, described Gibson’s Paradox in 1930 as “one of the most completely established empirical facts in the whole field of quantitative economics”, and Irving Fisher also wrote in 1930 that “no problem in economics has been more hotly debated”. Even Milton Friedman agreed in 1976 that “The Gibson Paradox remains an empirical phenomenon without a theoretical explanation”.[v]

But there is only one way for interest rates to go from the zero bound, it being only a matter of time. Commodity prices in their role as raw materials for production therefore seem set to rise with interest rates, if the paradox is still valid. And we have explained why the loss of a fiat currency’s purchasing power can be significantly greater in a stagnant, or even contracting economy, lending further support to rising producer prices for commodity inputs.

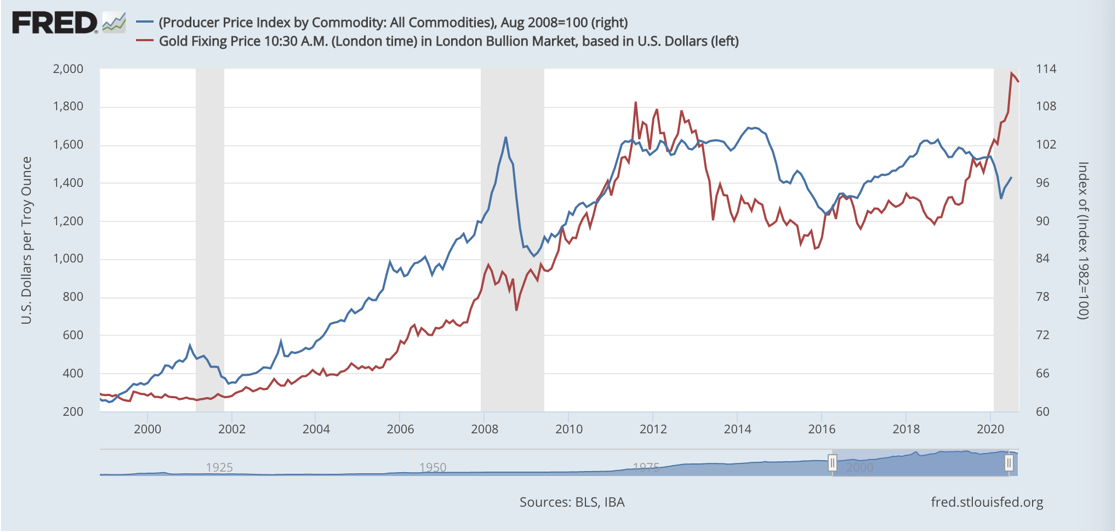

Furthermore, there is some evidence that producer prices are suppressed even more than the price of gold has been, as shown in the FRED chart below.

Since the turn of the millennium there had been a reasonable directional correlation between the price of gold and PPI prices until October 2018. At that point, PPI prices began to decline while the gold price turned higher from under $1200. It was clear that global trade was likely to decline, due to the tariff war between the US and China, with consequences for raw material demand.

In late March this year, the outlook changed from deflationary concerns to unlimited monetary inflation, driven by the Fed cutting its funds rate to zero on 16 March and the FOMC issuing a “whatever it takes” statement on 23 March. These events also marked the end of the PPI decline, and we can expect the corelation with gold prices to return, in which case the PPI index has some significant catching up to do.

This being the case, when the interest rate cycle turns the potential for higher raw material prices measured in dollars could be truly spectacular, even more so in the event that the gold price rises at the same time, which seems even more certain in the event that financial markets become destabilised by higher interest rates. It is an outcome consistent with a loss of purchasing power for fiat currencies to the extent it encourages economic actors to reduce and then abandon their currency balances entirely.

It is worth repeating at this point that the economic consensus on money and interest rates takes a diametrically opposite view to that indicated by Gibson’s paradox. If they expect a turn in the interest rate cycle, macroeconomists would complacently argue the dollar’s exchange rate would be driven higher, weakening commodity prices and gold.

Gibson’s Paradox says it will turn out otherwise, and it could be central to cementing the true relationship between interest rates, securities markets, and commodity prices. As a secondary issue, rising interest rates will be accompanied by a large fall in overpriced bond and stock markets as speculative positions are unwound, even undermining bank solvency ratios.

The flight of speculative capital from falling markets which is not lost has to go somewhere, particularly if cash balances held in the banks are at a growing risk from systemic default. Gibson’s paradox strongly suggests to us that these are the conditions for commodities to become the safe haven of choice for the highest levels of speculative money ever recorded since fiat currencies dispensed with their golden anchor. It is in this context perhaps we should note China’s aggressive buying of copper while selling US Treasuries: wittingly or unwittingly, they are acting correctly ahead of complacent macroeconomic western investors.