The Millennials Are Coming For The Boomers’ Money: One Bank Sees Generational Conflict Breaking Out This Decade

Tyler Durden

Sat, 09/12/2020 – 20:00

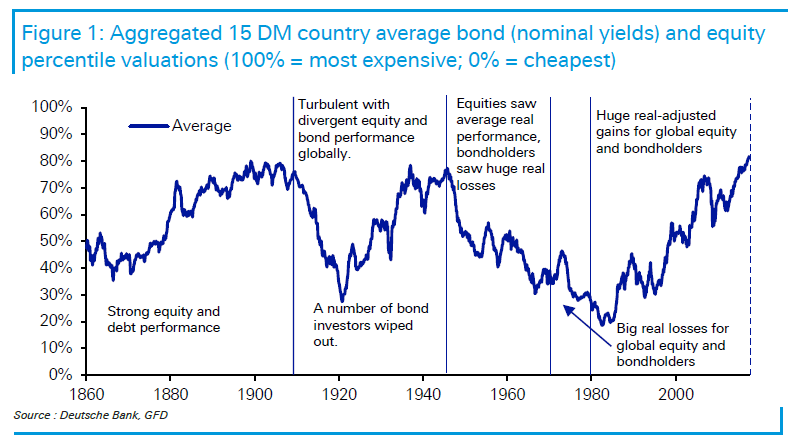

Late last week, we published the executive summary from Jim Ried’s latest must read long-term asset return study titled “Age of Disorder” in which the author makes the case that Economic cycles come and go, “but sitting above them are the wider structural super-cycles that shape everything from economies to asset prices, politics, and our general way of life” Having identified five such cycles over the last 160 years…

- The first era of globalisation (1860-1914)

- The Great Wars and the Depression (1914-1945)

- Bretton Woods and the return to a gold-based monetary system (1945-1971)

- The start of fiat money and the high-inflation era of the 1970s (1971-1980)

- The second era of globalisation (1980-2020?)

- The Age of Disorder (2020?-????)

… Reid thinks the world is on the cusp of a new era – “one that will be characterised initially by disorder.”

While there are extensive socio-economic and political implications as this new “Age of Dirsorder” replaces the current outgoing second era of globalization (touched upon here), one key aspect Reid focused on was the market (after all he is a banker), and specifically how current record high global valuations are threatened by the coming “new age”, which according to the Deutsche Bank strategist would have tremendous implications for eight major global themes from deteriorating US-China relations, to exploding global debt levels, to the coming runaway inflation and even worse wealth and income inequality, but perhaps most importantly to the coming generational conflict between the young (“poor” Milennials and Gen-Zers) and the old (i.e. rich).

Since the generational divide in not only the US but across the developed world has the potential to be even more disruptive than the record wealth gap, we will take a closer look at Reid’s observations on why the intergenerational gap has been widening in recent years and looks set to be even more of an issue in the immediate future.

* * *

The intergenerational divide to end this decade?

Inequality is a multifaceted area, and one sub-area of disorder to emerge out of it could well be the intergenerational divide. This has been widening in recent years and looks set to be even more of an issue in the immediate future.

For now the generational divide is at relatively extreme levels. Those who’ve graduated into the labor market over the last decade have already experienced the twin shocks of the Global Financial Crisis and now the Coronavirus pandemic – the two worst economic shocks since the Great Depression in the 1930s. Young people have therefore lost out economically relative to their predecessors and are behind previous generations on issues from home ownership to student debt levels. Meanwhile, there is an increasing divide on other issues, for example in how young people have been among the most forceful in calling for action on climate change. And this is before we consider how young people will inherit the large national debt burdens that have been accumulated.a

These age divides have manifested themselves increasingly in political preferences, with more and more elections around the world taking place along generational lines.

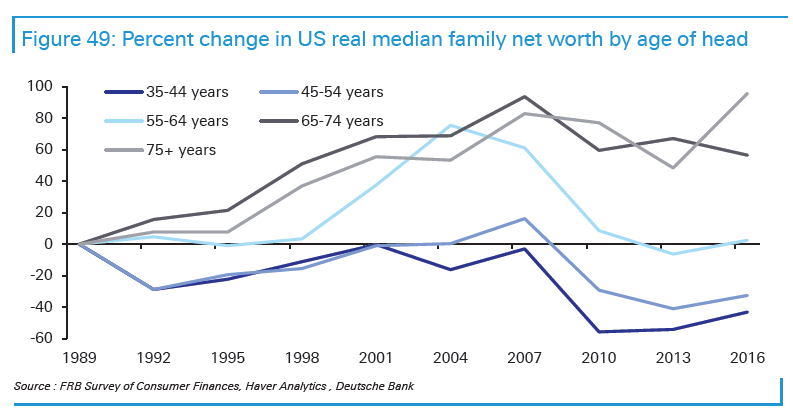

We think this intergenerational conflict will likely come to a head over the next decade. Ageing populations across the West are exacerbating many of these existing trends. High house prices and lagging income growth for Millennials and Generation Z in a number of countries continue to create anger and resentment. And the young have every right to be aggrieved. Figure 49 shows that in the US, real median net worth by age of head (of household) has diverged markedly since the 1980s.

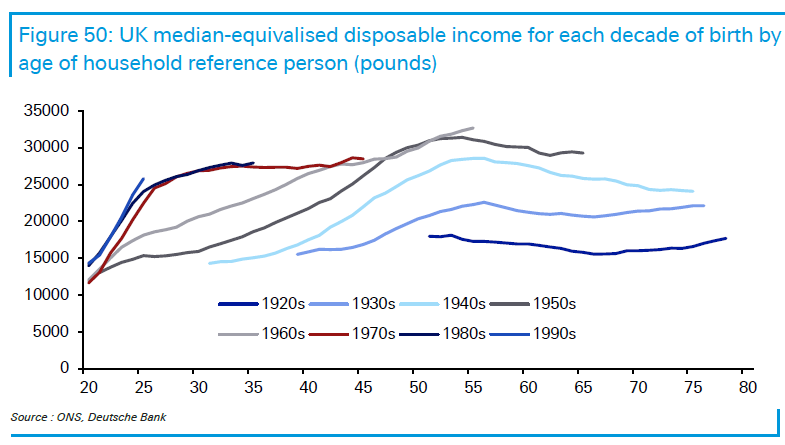

In the UK, the median household incomes of those born in the 1980s and 1990s aren’t doing much better than those born in the 1970s at a similar age. That’s a big difference from previous cohorts, where each tended to be noticeably better off ata given age than its predecessor.

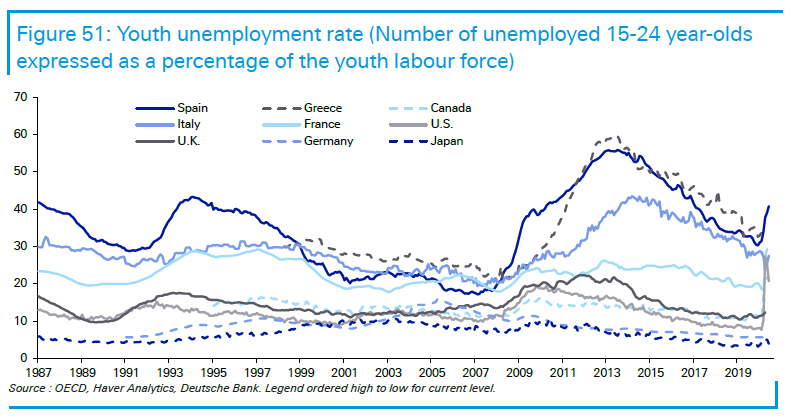

Meanwhile, thanks to the GFC and the Covid shock, youth unemployment has already spiked up once over the last decade and looks likely to do so again, especially relative to the rest of the population.

After the GFC and the subsequent sovereign debt crisis, youth unemployment peaked above 25% in France and above 50% in Spain and Greece. In the US and UK, it hit just below and just above 20%, respectively. Though these rates fell back in the following years, the impact of the Coronavirus pandemic has thrown away this progress, and young people have once again found their career prospects harmed by circumstances out of their control. Indeed, in America, the ranks of the jobless youths are greater now than they were at their peak after the financial crisis.

This legacy is likely to be a long-lasting one, even as the economy returns to growth. The evidence shows that for those who graduate in a recession, as many college and university graduates will be doing right now, not only is it harder to get a job initially, but wages suffer for years afterwards as well. Intuitively, this is because young people will be far less picky when it comes to accepting job offers and be more likely to accept a lower-paying role than they might have done in a stronger labour market.

So young people today have had the unfortunate luck to have experienced the two largest economic crises since the Great Depression. It is clear that young people today stand some distance from where previous generations were at the same age.

In general terms, today’s young are finding themselves priced out of the housing market, living with their parents for longer, and having to defer important life stages such as marriage and children. It is little wonder that many feel as though they’ve lost out relative to previous generations at the same point.

More recently, the generational divide has manifested itself in political preferences, with the young generally on the losing side, especially in binary referendums or two-party controlled systems. Although it has long been the case that young people have tended to lean leftward, this divide along age lines has become increasingly prevalent in recent years.

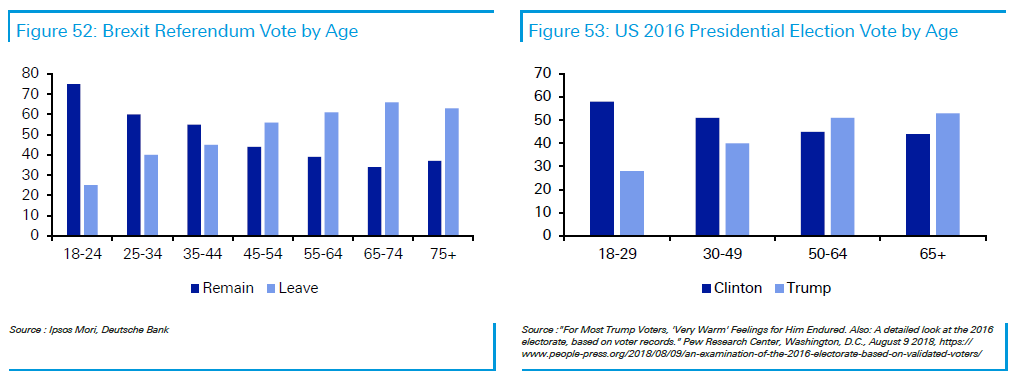

Just look at two of the biggest political decisions on either side of the Atlantic, the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump. Both saw such a divide along age lines, to the point that a large majority of young people faced an outcome they hadn’t voted for. The graphs show that the millennial generation (around 40 today) were the pivot to whether you were more or less likely to vote for Brexit or Trump.

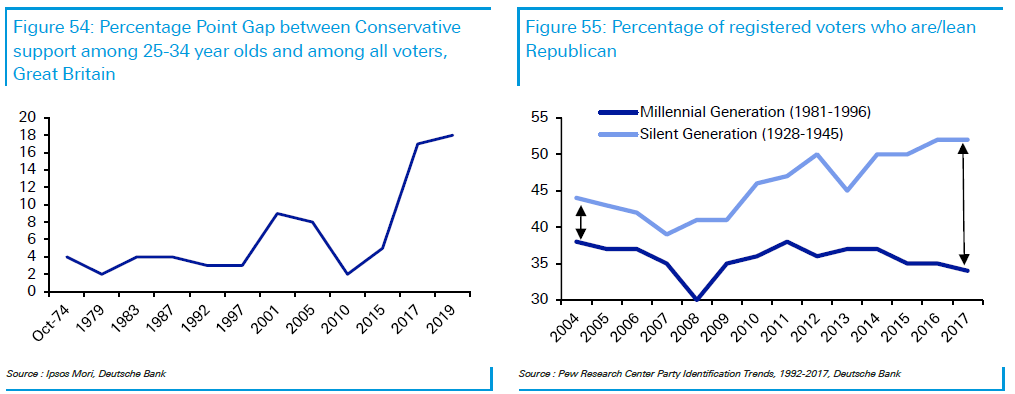

Of course, democracy always has a losing side. Yet it is a newer phenomenon that entire generations would conceive of themselves as the losers, and there is decisive evidence that this has widened over time. For example, look at the 25-34 year-old group in the UK and compare its support for the Conservative Party with the nationwide level. We’ve seen this in the US as well. The proportion of voters who identify as Republican or Republican-leaning has notably widened by generation over the last decade.

There is evidence that the backlash has started even if the Millennials haven’t quite had the weight of numbers. In the last couple of UK elections, the strongest support for the opposition Labour Party has been from younger voters, supporting a manifesto that included measures directly targeted at them, such as the abolition of tuition fees, or preventing rents from rising by more than inflation. Indeed, despite their defeat in the December 2019 general election – where the elder generations’ support of Brexit held sway – they did unexpectedly well back in the 2017 contest, winning 40% of the vote. Similarly in the US, Bernie Sanders, a self-described democratic socialist, was propelled in part by enthusiasm among younger voters towards his left-wing policies, and in both 2016 and 2020 he was the runner-up for the Democratic presidential nomination and was a favourite for a period late in the race in the latter bid.

This isn’t just a US or UK phenomenon. In continental Europe, the most popular candidate in France’s 2017 presidential election among 18-24 year olds was neither President Macron nor Marine Le Pen, but the left-wing Jean-Luc Mélenchon. In Ireland’s election earlier this year, Sinn Fein received the most first-preference votes, partly because of discontent at the lack of affordable housing, thanks to strong support from younger voters. Again, getting over the line has been tough in most places as their demographic doesn’t have a majority – but returning to the French election of 2017, a small % swing in the first round easily could have led to the second-round run-off being between two extreme candidates: Le Pen and Mélenchon.

Looking forward, if this younger generation is unable to achieve its economic aspirations – particularly now, given the effects of the pandemic – why should its views on these economic issues change as the members age, as many assume? Indeed, this young demographic could soon mobilise itself into an electoral majority.

A potential disruptive reversal in power

The general assumption is that the intergenerational divide will worsen as the population ages and that this group will ensure that the self-interest of the status quo continues. However, this misses the key point that the age where the intergenerational divide begins is not static. It is likely that this age will increase over time as the average age of those left behind will continue to increase as a gap has opened up in income and wealth that is very hard to bridge naturally. As such, at some point the younger left-behind generation will exceed those that have benefited from the favourable financial conditions that have been cemented in successive recent elections. When this happens, the possibility of seismic change in policy at elections becomes more likely. We think that over the next decade, the left-behind younger population will become an increasingly powerful electoral force, especially if it continues to be left behind due to the impact of the pandemic.

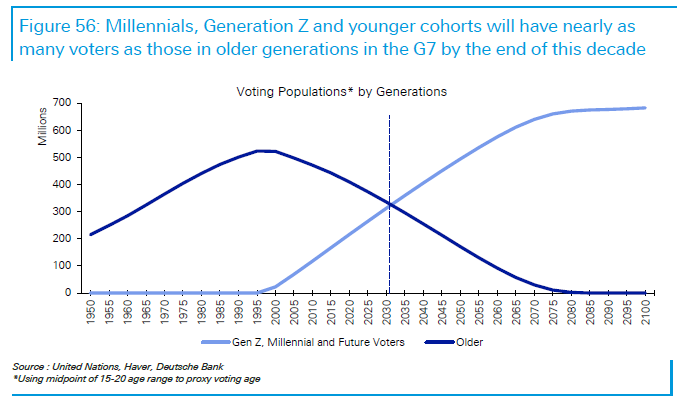

Figure 56 looks at the Millennial, Generation Z and younger cohorts relative to those born prior to the Millennials in G7 countries on an unweighted aggregated population basis. We have only included those of a voting age in each year past and future. Given the UN data base works in five-year buckets, we’ve assumed those aged in the middle of the 15-20 year-old bucket as being eligible to vote.

The generations prior to the Millennials have held the upper hand, and by a sizeable majority, in recent decades. As recently as 2005 the elder group held a 497,000 vs 69,000 electoral advantage in G7 countries. By 2015 (around the time of Brexit and Trump votes) this was a still strong 442,000 vs. 167,000 advantage. However, as we approach 2030, this gap will narrow towards zero, and after that all those born after 1980 will start to dominate elections.

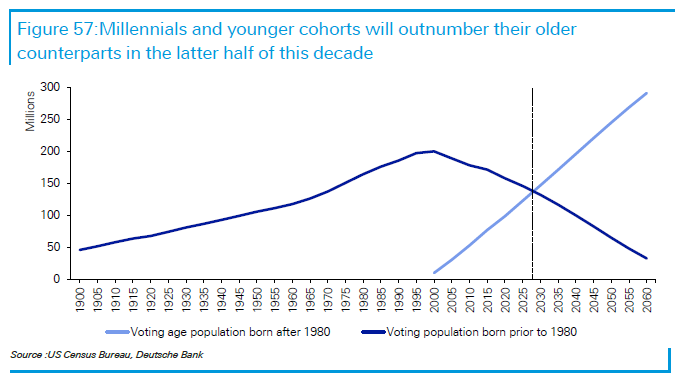

Assuming there won’t be a large number of Millennials that find economic life much more economically favourable as they age, this could be a turning point for society and start to change election results and thus move policy. In the US, where we can use the census to get even more granularity, 2020 looks set to be the last election where the Millennials and younger have a distinct disadvantage. The Census compilers have slightly more aggressive estimates than the UN and believe that by around 2028 they will reach voting parity in terms of numbers. It will be relatively close in 2024. For context in 2016, the advantage was 156,000 voters to 92,000 voters in favour of the elder group

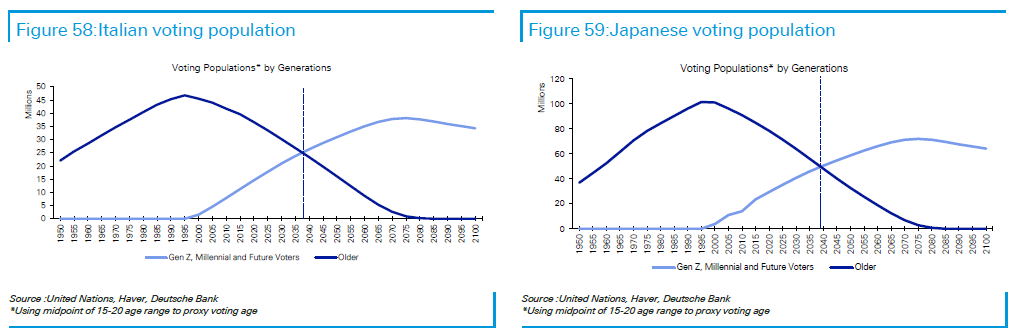

Interestingly of the G7, Italy and Japan see the crossover between the two groups occurring as late as 2035-2040, which reflects their poorer relative and absolute demographics going forward. This may help explain why Japan continues to be dominated by the elderly interest groups as population growth from the Millennial generation onwards has simply not been enough to threaten the pre-1980s cohort’s dominance. It also suggests that countries like the US and the UK, where the young vs old voter dominance happens much sooner (between 2025 and 2030), won’t necessarily see the same economic trends as what Japan has seen in recent years and is likely to see going forward. The crossover in Germany and France likely occurs in the early 2030s, so even here the themes of younger voters will increasingly be felt as we move through the upcoming decade.

So the 2020s looks set to be the decade where the Millennials and those that follow them make large numerical inroads into the electoral base of the older generation. Although the intergenerational divide is likely to get worse first as they continue to be outnumbered and are left with the Covid-19 shock, it is increasingly feasible that they could usher in a seismic change in a major election within the next decade. As such, we suspect that the electoral dominance of the pre-Millennial coalition is drawing to a close, and when it turns it could have a dramatic impact on the intergenerational divide and the self-reinforcing policies and economic outcomes of the “Globalisation era”.

As a caveat, we should say that this analysis assumes equal voter turnout, which history suggests is notably lower for the young. However, this isn’t set in stone and if a movement develops that the young feel strongly about and think they can win, then voter turnout could change. Also, this analysis assumes that Millennials don’t simply inherit the attitudes and wealth of the older generation as they age and become part of the vested interest group of the older generation. Given the generational gap in home ownership, income and debt, it will be difficult for different age groups to naturally bridge the financial divide that has opened up. We should stress that many in the elder generation support alternative politics vs the majority of their own age group – so as we get closer to a 50/50 split, a change in the political direction of travel can occur anytime, with a coalition of voters.

An electoral victory for the post-Millennial generation would likely usher in a reversal of policies that have favoured those born before, say, 1980. These could include a harsher inheritance tax regime, less income protection for pensioners, more property taxes, higher top-end income taxes, higher corporate taxes and more all-round redistributive policies. The “new” generation might also be more tolerant of inflation insofar as it will erode the debt burden it is inheriting and put the pain on bond holders, which tend to have a bias towards the pensioner generation.

Even without an extreme electoral shift, as the left-behind post-Millennial generation becomes more electorally powerful, it is likely to increasingly shape the policies of more mainstream parties. So even without a seismic shift, we still may be in the process of shifting from an era where boomer-type policies were in the ascendancy to one where Millennial preferences start to have a serious impact on politics. In terms of asset prices, most assets are simply transferred from one generation to another at a market-clearing price. Unless the post-Millennial generation has a sudden income boost, the price it will be prepared or able to pay for the assets of the pre-Millennial population – as the latter wants or needs to sell – will likely be under some pressure relative to past growth, especially the stunning growth of the “Globalisation Era”.