In the aftermath of the storming of the U.S. Capitol last week, there’s been a confused cacophony of calls to “put the rioters on the no-fly list“.

At the same time, there have been equally confusing claims and denials that some people found out that they had already been “put on the no-fly list” when they were denied boarding on flights home from Washington.

Are these people “on the no-fly list”? Could they be? Should they be? Is this legal?

More generally:

How do you get on the no-fly list? How do you know if you are on the list? How do you get off? What substantive and procedural legal standards apply?

The answers to all of these questions are much more complicated, and different, than many people seem to think — including the chairs of relevant Congressional committees, who ought to know better. The reality is that:

- There isn’t just one U.S. Federal government no-fly list — there are several, created by different agencies for different purposes.

- There are also non-list-based ways that real-time no-fly decisions can be made.

- No-fly decisions can be, and are, made independently, on the basis of different lists and other criteria, by multiple Federal agencies and by individual airlines.

So a better starting point for understanding what’s happening — before we can begin to assess whether it is legal or what should be happening — is to ask, “How can a would-be passenger be prevented from boarding a scheduled airline flight?”

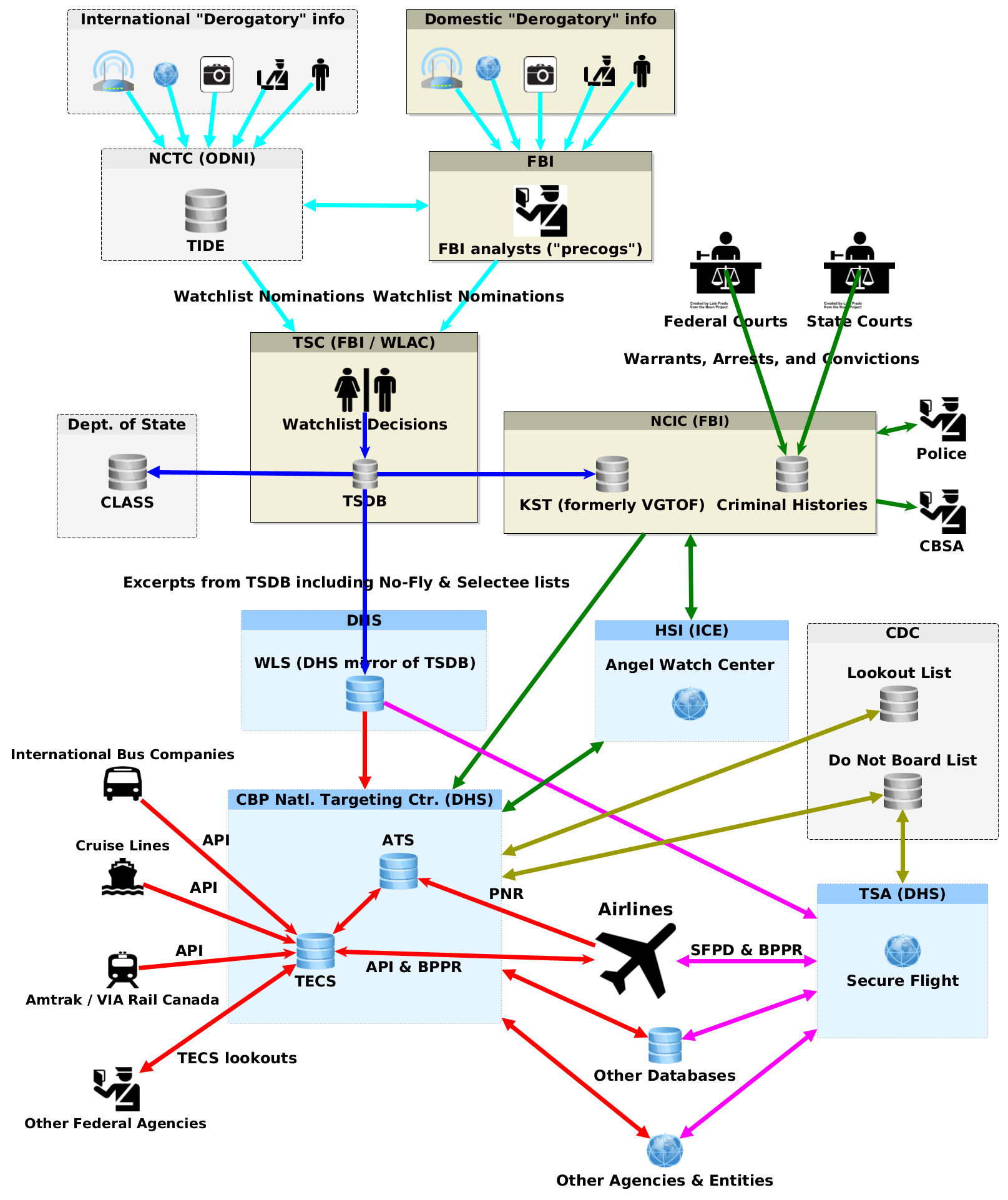

The diagram above (larger version; PDF with legend of acronyms and color-coding) gives only a summary of the U.S. government’s no-fly decision-making process. (We’ve published versions of the diagram before. The latest version above has been updated to include the Angel Watch Center, the CDC Do Not Board List and Lookout List, and the Watchlisting Advisory Council.)

As discussed in more detail below, no-fly decisions can be based on any of the following:

- U.S. government no-fly orders:

- Suspected terrorists and others associated with them (Terrorist Screening Database).

- People not suspected of terrorism, but flagged by real-time profiling algorithms implemented in the TECS/ATS or Secure Flight systems.

- Suspected infectious disease carriers (CDC Do Not Board and Lookout Lists).

- Arrest warrants (from NCIC, effectuated for international flights through TECS).

- People previously convicted, at any time in their life, of certain sex-related offenses (Angel Watch Center, for international flights).

- Airline no-fly decisions, based on:

- Airline conditions of carriage.

- Airline no-fly lists (created and maintained separately by each airline).

- Other non-list-based “rules” interpreted and enforced by airlines (most significantly the Timatic “travel information manual”).

How does all this work? Here are some FAQs about the no-fly list and no-fly orders:

How do you get on a no-fly list, or get prevented from boarding an airline flight?

Since 2008, all domestic and international passenger airline travel within, to, from, via, or overflying the U.S. has been operated on a permission basis, with a default of “No”.

Before any airline can issue a boarding pass, it must send information about the would-be traveler and their flight reservations to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and receive a favorable Boarding Pass Printing Result (BPPR) message granting individualized, per-passenger, per-flight permission to travel. Whether or not it approves issuance of a boarding pass, the BPRR can also include a handling code directing airline and/or TSA checkpoint staff to subject the passenger to more intrusive search at the airport, or to delay them while the police are called to detain, search, interrogate, and/or arrest them.

The algorithmic systems that process and respond to these permission requests include list-based rules (no-fly lists) and non-list based rules (pre-crime predictions). You can be kept off a flight by these profiling and scoring rules based on an automated decision made in real time, when you request a boarding pass, even if you are not and never have been on any blacklist or watchlist or the subject of any individualized suspicion.

Become an Activist Post Patron for just $1 per month at Patreon.

Permission requests for domestic and international flights are handled by different DHS components, based on submission of different datasets from airlines.

For domestic flights, the airline must send Secure Flight Passenger Data (SFPD) intended to identify each passenger and their flight itinerary to the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), which processes SFPD through the Secure Flight system. Secure Flight algorithms include some list-based rules and some profiling and scoring rules as well as optionally triggered calls to external systems and/or to manual interventions.

For international flights, the airline must send Advanced Passenger Information (API) and the complete Passenger Name Record (PNR) for each passenger to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which processes API and PNR data through TECS and the Automated Targeting System (ATS) to decide whether to send back a BPPR.

API for international flights is roughly comparable to SFPD for domestic flights, although (to the annoyance of airlines) the data elements and transmission formats demanded by TSA and CBP for domestic and international and flights respectively are slightly different.

PNR data, the additional data demanded by CBP for international flights, consists of complete mirror copies of reservations records from airlines’ internal commercial databases. These are vastly more detailed and intimately revealing. Did you request a halal meal? Behind the closed doors of your hotel room, if your flight and hotel were booked together, did you and your traveling companion ask for one bed or two? That’s in your PNR, and gets sent to CBP to be stored in your permanent file.

TECS is the name of the system in which the algorithms are executed, in response to each API message, to generate a BPPR for an international flight. ATS is a legal term of art used for Privacy Act purposes for a particular “System of Records”, not necessarily a separate database. Some ATS data is stored in TECS, and some is stored in other related databases.

Algorithmic processing by CBP in TECS and ATS for international flights is similar to that done by TSA in the Secure Flight system for domestic flights, except that TECS and ATS “ingest” and include pointers and links to more data sources, more other government agencies, and more external entities, and enforce a larger ruleset.

Unlike Secure Flight, ATS and TECS are connected to the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) operated by the FBI. This connection enables CBP to “vet” prospective international airine passengers against “wants and warrants” recorded in NCIC. So far as we can tell, the TSA isn’t yet able to include arrest warrants in its Secure Flight ruleset for domestic air travelers, although we have gotten repeated tips that TSA wants to do so.

As a database aggregated from information supplied by thousands of state and local law enforcement agencies and courts, NCIC is notoriously inaccurate, especially with respect to warrants. Often a local authority notifies the FBI when a warrant is issued, but doesn’t bother to tell the FBI to remove the warrant record from NCIC when it is cancelled. So connecting Secure Flight to NCIC would undoubtedly result in numerous false arrests of innocent air travelers on the basis of obsolete warrant records.

Also unlike Secure Flight, ATS and TECS are connected to the Angel Watch Center operated by Homeland Security Investigations (HSI). HSI is a unit of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which generally has no jurisdiction over the movements of U.S. citizens. But the Angel Watch Center carries out lifetime monitoring and enforces advance notice requirements for international travel by anyone who has ever been convicted of certain (vaguely defined) sex-related offenses — most of whom are U.S. citizens. Permission for international travel isn’t always denied to all of these people. But permission can be withheld if they haven’t provided sufficient or sufficiently detailed advance notice of their travel plans, or if their intended destination objects to their travel. The intent of the system is to function as a de facto lifetime ban on international travel.

Both Secure Flight and TECS also incorporate travel blacklists of suspected infectious disease carriers created by the Centers for Disease Control, and Prevention (CDC) in their rulesets.

Secure Flight checks passengers on domestic flights against the CDC’s Do Not Board List. TECS also checks passengers on international flights against the CDC’s Public Health Lookout List , using it to generate alerts from API data in advance of planned travel.

The CDC Lookout List is yet another example of mission creep: Since TECS already had the capability to include “Lookout” rules that generate an alert to an agent with other Federal law enforcement agency whenever CBP receives API data about planned international travel by a person of interest identified by passport number, phone number, or other data in the lookout rule, CDC figured it might as well use the full TECS feature-set and create lookout alerts in addition to the rules containing its Do Not Board List. (TECS alerts are themselves an earlier example of mission creep, and susceptible to all sorts of abuse. They can be, and are, used for surveillance and targeting purposes having nothing whatsoever to do with either aviation security or enforcement of customs or immigration laws.)

Once the BPRR control lines for prior restraint of air travel had been installed in airline IT systems, and the algorithmic decision-making system established, it was easy — and irresistibly tempting — to augment the algorithms by adding new list-matching, scoring, profiling, and action-triggering rules to the ruleset. Anyone who has ever managed the ruleset in a computer security firewall or device will be familiar with the process.

Mission creep has already occurred, as the system expanded from blocking perceived terrorist threats to also block perceived sexual threats and perceived disease threats.

When a traveler is refused transport, they usually ask whatever airline staff they are dealing with, “Why?” The typical answer is, “That must mean you are on the no-fly list.” But that’s almost always uninformed speculation, and shouldn’t be relied on as fact. The most that airline staff really know or can truthfully say is, “Because the government won’t give us permission to let you on the plane.”

In most cases, the airline receives only the Boarding Pass Printing Result (BPPR) from DHS. The airline may also receive a handling code as part of or with the BPPR, instructing it to take some action. But unless some DHS component or some other agency (responding to a TECS alert) contacts the airline or local police or shows up at the ticketing or check-in counter, the airline receives no information about what factor(s) or rule(s) in the algorithm triggered the no-fly decision or the non-response to the boarding pass permission request.

The airline has no idea whether they were not given permission to issue you a boarding pass because you are on a no-fly list — or, if so, which such list — or because some data (and if so, which data) in your travel history dossier, your flight reservations, or some other linked database triggered a pre-crime no-fly rule even though you weren’t on any blacklist.

So much for the government. But that’s only half the battle.

If the U.S. government gives you permission to fly (or, more precisely, gives the airline permission to issue you a boarding pass), the next step is for the airline to decide whether, based on its own criteria, it is willing to transport you. Sometimes this might happen when you try to buy a ticket, even before the airline has sent your reservation data to the DHS with a boarding pass printing request. But most airline no-fly decisions are made or communicated to would be passengers later, at check-in or at the boarding gate.

It’s for this reason that the TSA says, probably truthfully, that people trying to fly home from the Capitol riot who were denied boarding at the gate or kicked off planes after they had boarded were probably being denied air transport as a result of airline decisions, not as a result of any of the Federal government’s no-fly lists or no-fly profiling algorithms.

Like the government’s fly/no-fly decision-making algorithms, airlines apply both list-based no-fly rules and non-list-based no-fly criteria. Each airline applies its own criteria and procedures, incorporating its own proprietary blacklist and ruleset.

But fly/no-fly decision-making by airlines differs from that of the U.S. government in two major ways.

First, for an airline the default is generally “Yes”, whereas for the U.S. government, as discussed above, it has been “No” since at least 2008. If you have a ticket, you look more or less alive and human, your clothing covers your “naughty bits”, and you don’t break any rules (more on that below), the airline will generally let you on the plane. You don’t (usually) have to prove that you aren’t a terrorist.

Second, airline procedures generally involve a greater degree of human discretion and judgement on how to interpret and apply the fly/no-fly criteria. Airlines would say that this allows flexibility (sometimes good) but it also allows arbitrariness (bad). For better or worse, whether you are allowed to fly can depend on a gate agent’s temper and mood.

What are the ostensible criteria for airline no-fly decisions?

One, airlines reserve the right, and sometimes exercise it, to refuse to transport anyone who isn’t in compliance with the general conditions of carriage in their tariff when they show up at the check-in counter or boarding gate. This is most often applied to would-be passengers who are loudly and angrily drunk or acting violently, although typical airline conditions of carriage include a surprisingly long list of attributes and behaviors (offensive body odor, etc.) that can render a person ineligible for transportation.

There’s been some litigation over these rules, and Federal courts have followed normal judicial procedures in reviewing airline actions based on rules in conditions of carriage. In general these rules have held up to court scrutiny as long as they are explicitly stated, not unduly vague, and not enforced in a demonstrably discriminatory way.

Two, airlines claim the right, and sometimes exercise it, to put people on their private internal no-fly lists. Each airline has such a list, which they create and maintain on their own. Delta Air Lines, for example, recently said it has put 880 people on its no-fly list because they refused to comply with its rules requiring face masks.

It’s not clear that airlines acknowledge any obligation to have, or to disclose, any reason for banning a would-be customer, or to provide any due process with respect to blacklisting decisions. When they issue a ban-and-bar notice, they typically act as though they think that they have “the right to refuse service to anyone.” But that’s exactly what airlines aren’t allowed to do. Like any licensed common carrier, an airline has a duty to transport any passenger willing to pay the fare and comply with the rules in its published tariff.

The most common fact pattern is that, after some sort of “incident” in flight or at an airport, an airline will notify a person that they are unwelcome on future flights on that airline. Diverting a flight is very expensive, and if the pilot makes an unscheduled landing to kick you off the plane because you assaulted other passengers or crew, you are likely to have to continue your journey on another airline, or by other means.

But it’s not at all clear that your having violated airline rules in the past is lawful grounds for an airline or other common carrier, on its own say-so, to ban you from future flights. If the airline thinks that you are likely to commit some future violation of the law, the proper course is not for them to take the law into their own hands, but to go to a court and request an injunction or restraining order restricting what would otherwise be your rights.

Unlike landlords who share blacklists of problem tenants and casinos that share blacklists of card counters, airlines don’t generally share their no-fly lists. So it’s common for someone kicked off a flight and banned them from future travel on Airline X to buy a new ticket and continue their journey from the same airport on the next flight on Airline Y.

Three, airlines apply other “rule-based” criteria, not based on lists or individualized conduct-based banning orders, to decide which passengers they are willing to transport.

The most important and most frequently-invoked of these rules is the requirement invariably included in airline tariffs and conditions of carriage for each passenger on an international flight to have “all documents required” for their intended destination.

What documents, if any (such as a passport with a specific amount of remaining validity time, a visa, and/or an onward or return ticket), are required for a specific passenger by the laws of a specific country is fundamentally a legal question.

Answering this question, in order to decide whether to not to let someone on a plane — which in the case of an asylum-seeker fleeing persecution can be a decision with life-or-death implications — is an essentially adjudicatory function. Airline staff have neither any qualifications nor any competence to answer potentially complex questions about other countries’ immigration and asylum laws, or to act as judges. But they do so anyway.

Governments, starting with the U.S., incentivize airlines to enforce their immigration and asylum laws, and to err on the side of denial of passage. Governments do this because outsourcing the denial of immigration and asylum claims to airline ticket offices and check-in counters abroad makes it harder for would-be immigrants and asylum seekers to challenge these denials in court in the U.S. or other would-be destination countries.

When airlines substitute their front-line ticketing and check-in staff for courts as immigration and asylum judges of first and last resort, they also substitute the Timatic travel information manual for the laws they enforce. If front-line airline staff read Timatic as saying that you need a visa, based on your destination, citizenship, duration of intended stay (as inferred from your onward or return flight reservations), etc., or that you need evidence of a particular vaccination, they enforce that rule as they read it in Timatic.

Timatic is available as a pocket book, but also through all of the major computerized reservation systems (CRSs) used by airlines. Timatic is a paid subscription service. If you want to know what Timatic says about entry requirements, in order to guess whether you will be allowed to fly, free but usually partial public interfaces to Timatic are sometimes provided by airlines , visa services, and online travel agencies, although these come and go. A full interface to exactly the same Timatic data in the same format as is provided to airlines is available with a paid subscription to Expertflyer.com through its CRS gateway.

Airline staff make no attempt to read, much less interpret, foreign laws. How could they? That’s what Timatic is for. Timatic is compiled and published by the international airline trade association, IATA, to provide an aggregated, translated summary, in standardized format, of the entry requirements of every country in the world. Timatic has no legal authority, but in practice is the definitive de facto rule book for international air travel.

To their credit, the authors and editors of Timatic do a very good job of summarizing national laws. originally in dozens of languages, from around the world. But Timatic is sometimes inaccurate. More significantly, Timatic is almost always incomplete.

By nature and intent, Timatic is only a summary of national laws. There are exceptions to many rules of law, and exceptions to the exceptions. Timatic tries to parse these hierarchies, but it can only go so deeply into the weeds. If Timatic says that you are inadmissible, airline staff who rely exclusively on Timatic — as they almost invariably do — will deny you boarding, even if you fall within some exception not mentioned in Timatic.

Timatic is less obviously but more fundamentally incomplete in being limited to national laws. Timatic does not mention international human rights treaty laws related to travel that take precedence over the laws of state parties to those treaties. And Timatic does not mention the international aviation treaties (or the implementing national legislation) that define airlines as common carriers and establishes their duty to transport all passengers.

Timatic implies that all travelers must have passports or other “travel documents”, which is what national laws in many countries (including the U.S.) say. But international treaty law recognizes the human right to leave any country and to return to one’s own country, as well as rights to air travel and rights of asylum seekers and refugees. As human rights, these rights are not limited to people in possession of government-issued documents.

Airline staff making fly/no-fly decisions at ticketing and check-in locations enforce their interpretation of national laws as they are described in Timatic, without regard for any of the international treaty rights that aren’t mentioned in Timatic.

Whether you would actually be admitted, or eligible to claim asylum, if you were able to reach your intended destination, is irrelevant. If airline staff at your planned point of departure read Timatic as saying that you won’t be admitted, you’ll never get a chance.

How do you get off a no-fly list, or get a no-fly order or decision reviewed by a judge?

As described above, no-fly orders can originate with different government agencies or private entities, and can be issued on the basis of different lists or algorithmic rules.

Not surprisingly, this means that the procedures (if any) for appealing a no-fly order or having it reviewed by a judge vary, depending on what entity issued the order.

Let’s start with no-fly orders issued by a U.S. government agencies to suspected terrorists:

At least one Secretary of Homeland Security (Michael Chertoff, a former Federal judge), said repeatedly and explicitly while he was head of DHS that he believed that no-fly decisions should be exempt from judicial review:

We don’t conduct court hearings on this…. we’re not about to let them do that… because we would be inundated with proceedings…. [W]hen we actually have identified a person … and we put them on the list … it’s not a subject for litigation…. But if you are asking if we would do a court process where we litigate it, I mean, that effectively would shut it down.

Congress has tried to make it as hard as possible to have no-fly orders issued to airlines by the TSA reviewed by Federal courts. As an initial matter, notice of these orders is given to the airline, not the would-be traveler, in the form of the Boarding Pass Printing Result (BPRR). The airline isn’t told the reason for the BPRR, but is told not to disclose the BPRR to the would-be traveler — even though they obviously know whether or not they are allowed to fly. The absurdity of this was noted by the judge in the one no-fly case to make it to trial:

Something’s going on in this case that’s strange, and I mean on the part of the government.

I don’t understand why you’re fighting so hard to avoid having this poor plaintiff know what her status [on the no-fly list] is.

It’s easy for anyone to buy a ticket and try to get on an airplane. If they’re allowed to fly, they know they’re not on the no-fly list. If they’re stopped and handcuffed and sent to jail in the back of a police car, they know they’re on the list.

If you can establish legal “standing” by getting the government to admit that it ordered the airline not to transport you, your next obstacle to judicial review is “jurisdiction”.

A special provision of Federal law intended to challenges to TSA orders, 49 U.S.C. § 46110, strips Federal District Courts where trials are held of their normal jurisdiction over any challenge to a TSA order. This law preserves only a fig leaf of a right to judicial review: Federal Circuit Courts of Appeal can review TSA orders, but only on the basis of whatever records the TSA chooses to hand up to the Court of Appeals, and with the appellate court required to defer to all of the TSA’s previous factual determinations.

A challenge to 49 U.S.C. § 46110 as an unconstitutional deprivation of due process, Sai v. Neffenger, has been pending in the First Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston since 2015. In the meantime, other cases challenging no-fly decisions have had a mixed record.

Only one no-fly case has gone to trial, resulting in something of a Pyrrhic victory: After eight years of litigation, Dr. Rahinah Ibrahim found out that she was put on the no-fly list because the FBI agent who interviewed her as part of his mosque-watching assignment misunderstood how to fill out the blacklist and watchlist “nomination” form. Dr. Ibrahim’s name was taken off that list. But her U.S. visa was revoked (despite the fact that her children were born in the U.S. and are U.S. citizens), and she hasn’t been able to return to the U.S.

Dr. Ibrahim’s pro bono lawyers incurred almost $4 million in expenses to overcome what the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals described as “scorched earth” and “bad faith” litigation tactics by the government. It took the lawyers another seven years to get paid, (finally, last month, fifteen years after they started working on the case) after the government appealed the fee award all the way to the Supreme Court.

Several other challenges to no-fly orders are pending, some as class actions. But the rulings in those cases to date have been mixed, and none of them has made it to trial.

Even if a challenge to a no-fly order makes to to trial, the government can declare certain information to be a “state secret,” making it inadmissible in court. In Dr. Ibrahim’s case, Attorney General Eric Holder submitted an apparently-perjured declaration to the court, claiming that it would “cause significant harm to national security” to reveal whether or why Dr. Ibrahim was on the no-fly list — even though the reason, as Atty. Genl. Holder knew, was that an FBI agent had made a mistake in filing out a form. The government has made similarly dubious “state secrets” claims in other no-fly cases.

As of now, you can’t count on much of a day in court if the U.S. government orders an airline not to transport you “because terrorism”, whether that no-fly decision is made on the basis of a list or of a pre-crime profiling algorithm.

Things are even less certain, although perhaps a little more promising, with respect to Federal no-fly orders that originate with the Angel Watch Center or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). So far as we can tell, neither of these types of no-fly orders has yet been challenged in Federal courts.

The Constitutionality of the law establishing the Angel Watch Center and purporting to grant it lifetime authority over international travel by certain U.S. citizens is questionable. One lawsuit challenging portions of the law was dismissed, but only because it was deemed premature when the regulations to implement the law had not been promulgated.

The CDC’s quarantine regulations, which were adopted in 2017 (over our objections and those of many others), make no provision for judicial review of quarantine orders. The regulations note the potential pathways to review of a quarantine order through a habeas corpus petition or a lawsuit under the Administrative Procedure Act. But the applicability of either of those proceedings to a CDC Do Not Board order remains untested.

There are FAQs on various government websites that purport to explain the criteria for some of these no-fly orders. But there’s no mention of no-fly lists or no-fly orders in Federal laws or regulations, and no statutory or regulatory criteria for no-fly decisions. The no-fly decision-making system is entirely extra-legal, limited only by agency self-restraint.

What about no-fly orders by airlines?

In practice, you can appeal a no-fly order by front-line airline staff at an airport ticketing or check-in counter to a supervisor or perhaps as far up the chain as the airline’s “station manager” on duty. That will probably do no good if the order comes from headquarters or is based on an earlier incident at another airport. But it may give you a chance to contest a judgement call as to whether you are currently in compliance with the airline’s conditions of carriage, or as to your eligibility for admission to the country of your destination.

If appeals to an airline supervisor are unsuccessful, see our FAQ on your rights at the airport and our advice on How to protect your right to a refund if an airline refuses to transport you. This advice applies regardless of the reason for the denial of transport, and will help make sure you have the evidence you need to sue the airline, if you later decide to do so, as well as to obtain a refund of whatever you paid for the ticket you can’t use.

In the absence of an allegation that you were not, at the time you presented yourself at the airport for your flight, in compliance with some specific rule in the tariff, denial of transport by an airline appears to be, on its face, a violation of its operating license and legal duties. It could be grounds for both a private Federal suit for damages and sanctions by the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT). However, we’ve been unable to find any record of litigation or DOT enforcement action regarding an airline-issued no-fly order.

John Gilmore, the founder of the Identity Project, was kicked off a British Airways flight in 2003 (before the launch of the Identity Project) for wearing a button identifying himself as a “Suspected Terrorist”. The DHS treats us all as suspected terrorists, so the statement made by the button was factually true as well as being political speech protected by the First Amendment. But John didn’t sue, and has taken his business elsewhere rather than trying to fly on British Airways again.

Should the people who stormed the Capitol be put on a no-fly list? If not, what should be done?

The overview above of no-fly lists and non-list-based no-fly orders provides some context for discussion about whether any of these restrictions on the right to travel should be imposed on some or all of the people who participated in the riot at the U.S. Capitol.

Before we jump to apply summary extrajudicial restrictions on fundamental rights, though, shouldn’t we first consider using normal (and Constitutional) judicial procedures?

Injunctions and temporary restraining orders are issued tens of thousands of times a day, most often on the basis of complaints of domestic violence, to restrict the movements of people who have been proven, to the satisfaction of judges, to pose a defined threat. Often the subjects of these orders are banned from a specific location, such as within so many feet of a past victim’s residence. There is a vast body of case law with respect to the substantive and procedural standards for the issuance by courts orders like this.

Why can’t Federal authorities ask Federal courts to issue injunctions to restrict specific individuals, organizations, or activities, in particular places and at particular times, that pose a threat to the Capitol, members and staff of Congress, or other lawful activities?

There is a history of use and sometimes misuse of injunctions restricting members of the public from being or congregating in specific places at specific times. We don’t have to get into all of the issues these court orders pose for the right to assemble to say that, to the extent such orders are ever appropriate, they should come from the courts.

With respect to people who have been charged with crimes, restrictions on travel can be, and often are, imposed by court order as a condition of release pending trial. But whether such restrictions are justified in particular circumstances is a matter of extensive case law and well-established judicial procedures for the issuance and appellate review of orders setting conditions of release. What’s so broken in this system that we would need something new, with all the risks of bypassing the judiciary, to deal with the Capitol riot?

We find it especially ironic that calls to deploy measures like extrajudicial no-fly orders are being made by politicians who profess to be those most committed to the rule of law. The current no-fly system, as should be apparent from the description above, is the antitheses of the rule of law, and epitomizes the lawlessness of the DHS in particular.

Does everyone convicted of a crime belong on the no-fly list? If so, for how long after their conviction? What about people suspected or accused of crimes? And why shouldn’t these decisions be made by judges?

Why should we focus on air travel, anyway? Surely those who came to Washington by air were less likely to have brought firearms or explosives than those who came by car.

This seems to be an example of the “If you build it, he will come” syndrome. Because the no-fly system exists, we are tempted to use it against whomever the demons of the day are.

We’ve seen where that leads during times of “Red Scares”, witchhunting, and blacklists, when anyone defined as an enemy by J. Edgar Hoover could be denied a passport, denied a government job, or subjected to other extrajudicial restrictions on their lawful activities.

Is this what we want to go back to, or forward to? Do we want the U.S. to be like China, where only those with the highest “social credit” scores are allowed to fly, while those with the lowest scores are also barred from travel by high-speed train?

Some politicians, and Amtrak’s CEO, seem to think so. Last week Amtrak’s CEO issued a statement that, “We call upon Congress and the Administration … to expand the TSA’s ‘No Fly List’ to rail passenger service.” We say no. Expanding the airline no-fly system to Amtrak will only widen the bad consequences of its defects, and further consign less-favored travelers to Greyhound as the long-distance carrier of last resort for the undocumented.

You may have noticed that Amtrak shows up at the lower left in the diagram above. Amtrak sends API data for passengers on its few international trains (to and from Canada) to CBP. But as of now, so far as we can tell from CBP’s responses to requests for travel records and Amtrak’s (still incomplete) responses to our Freedom Of Information Act requests, Amtrak’s data-sharing with CBP is still (1) limited to passengers on international trains, and (2) a one-way feed of passenger surveillance information, not an interactive permission system. So far as we can tell, Amtrak hasn’t yet installed anything comparable to the BPPR control lines that give CBP and TSA the ability to exercise prior restraint of air travel.

Is there a place for a no-fly list? We don’t have to answer that question to say that any no-fly list should be limited to people who have been barred from air travel by court order. The role of the DHS should be purely clerical: compiling the list of those named in injunctions and restraining orders issued in accordance with established judicial procedures.

So far as we can tell, neither the DHS nor any Federal law enforcement agency has ever requested a no-fly injunction or restraining order from a Federal court. It would be premature to conclude that court orders are inadequate to address the threat posed by the Capitol rioters — or anyone else — when this normal legal approach has never been tried.

For the DHS or some other non-judicial government agency to arrogate to itself the authority to put names on a no-fly list on its own say-so is as illegitimate as it would be for the FBI to decide that, because the FBI is charged with maintaining a list of outstanding arrest warrants in NCIC, the FBI should be entitled to enter names into NCIC as subject to arrest, without having to those warrants approved by a judge. That’s just wrong.

Source: PapersPlease.org

H/T: MassPrivateI Blog

Top image: Change.org

Subscribe to Activist Post for truth, peace, and freedom news. Send resources to the front lines of peace and freedom HERE! Follow us on Telegram, SoMee, HIVE, Flote, Minds, MeWe, Twitter, Gab and Ruqqus.

Provide, Protect and Profit from what’s coming! Get a free issue of Counter Markets today.