The Fed Can’t Fix What’s Broken

Authored by Lance Roberts via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

The Federal Reserve is poised to spray trillions of dollars into the U.S. economy once a massive aid package to fight the coronavirus and its aftershocks is signed into law. These actions are unprecedented, going beyond anything it did during the 2008 financial crisis in a sign of the extraordinary challenge facing the nation.” – Bloomberg

Currently, the Federal Reserve is in a fight to offset an economic shock bigger than the financial crisis, and they are engaging every possible monetary tool within their arsenal to achieve that goal. The Fed is no longer just a “last resort” for the financial institutions, but now are the lender for the broader economy.

There is just one problem.

The Fed continues to try and stave off an event that is a necessary part of the economic cycle, a debt revulsion.

John Maynard Keynes contended that:

“A general glut would occur when aggregate demand for goods was insufficient, leading to an economic downturn resulting in losses of potential output due to unnecessarily high unemployment, which results from the defensive (or reactive) decisions of the producers.”

In other words, when there is a lack of demand from consumers due to high unemployment, then the contraction in demand would force producers to take defensive actions to reduce output. Such a confluence of actions would lead to a recession.

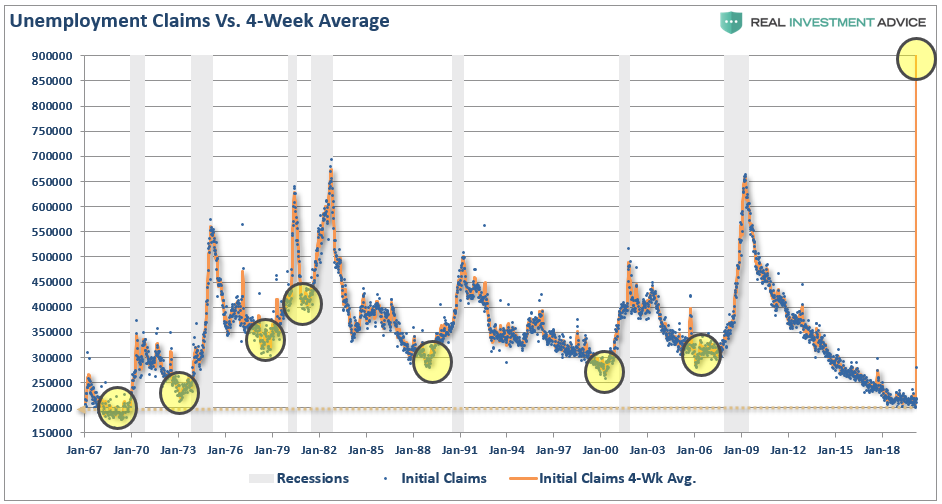

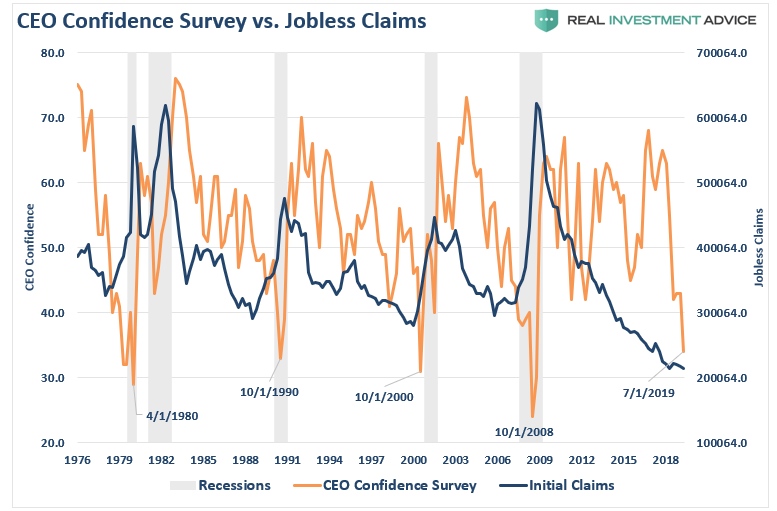

On Thursday, initial jobless claims jumped by 3.3 million. This was the single largest jump in claims ever on record. The chart below shows the 4-week average to give a better scale.

This number will be MUCH worse next week as many individuals are slow to file claims, don’t know how, and states are slow to report them.

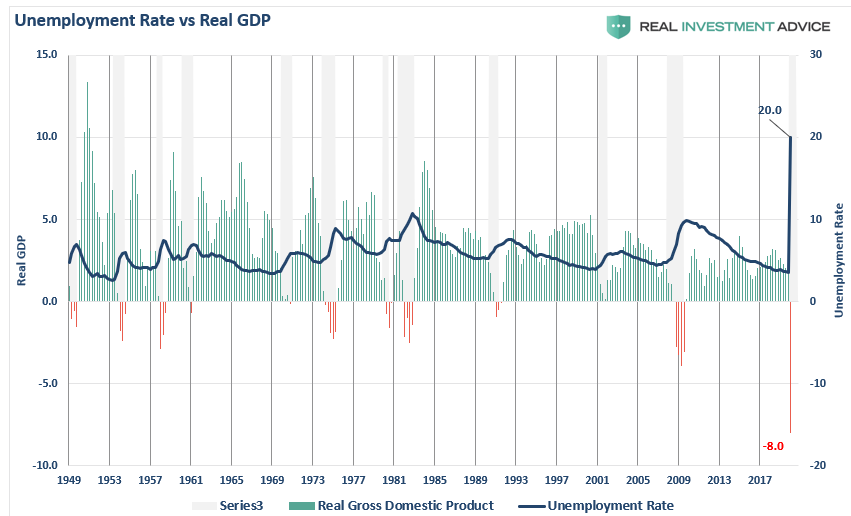

The importance is that unemployment rates in the U.S. are about to spike to levels not seen since the “Great Depression.” Based on the number of claims being filed, we can estimate that unemployment will jump to 20%, or more, over the next quarter as economic growth slides 8%, or more. (I am probably overly optimistic.)

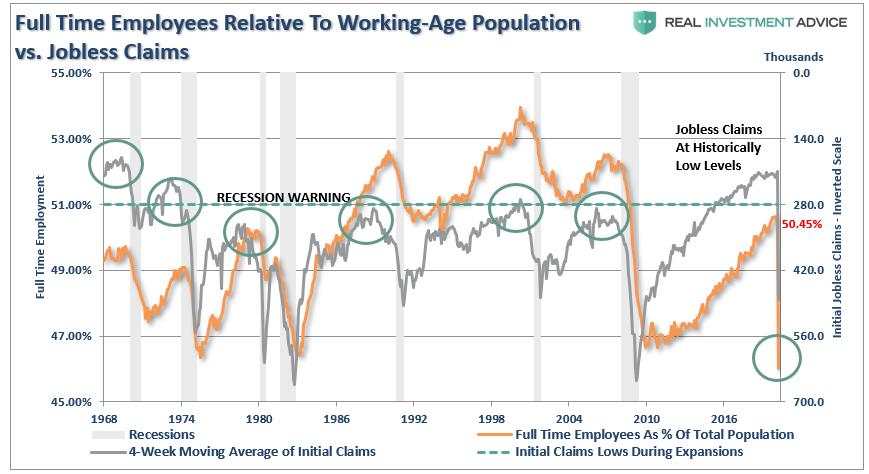

More importantly, since the economy is 70% driven by consumption, we can approximate the loss in full-time employment by the surge in claims. (As consumption slows, and the recession takes hold, more full-time employees will be terminated.)

This erosion will lead to a sharp deceleration in economic confidence. Confidence is the primary factor of consumptive behaviors, which is why the Federal Reserve acted so quickly to inject liquidity into the financial markets. While the Fed’s actions may prop up financial markets in the short-term, it does little to affect the most significant factor weighing on consumers – their job.

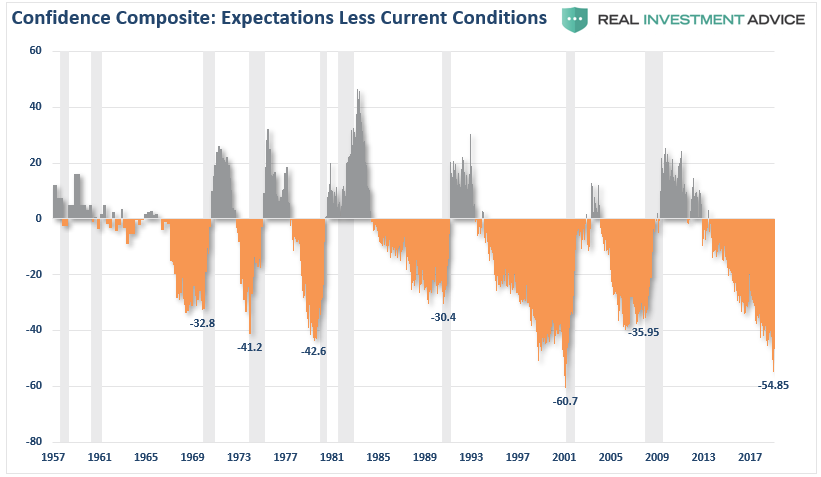

Another way to analyze confidence data is to look at the consumer expectations index minus the current situation index in the consumer confidence report.

This measure also says a recession is here. The differential between expectations and the current situation, as you can see below, is worse than the last cycle, and only slightly higher than prior to the “dot.com” crash. Recessions start after this indicator bottoms, which has already occurred and will show up when the current data is released.

Importantly, bear markets end when the negative deviation reverses back to positive.

While the virus was “the catalyst,” we have discussed previously that a reversion in employment, and a recessionary onset, was inevitable. To wit:

“Notice that CEO confidence leads consumer confidence by a wide margin. This lures bullish investors, and the media, into believing that CEO’s really don’t know what they are doing. Unfortunately, consumer confidence tends to crash as it catches up with what CEO’s were already telling them.

What were CEO’s telling consumers that crushed their confidence?

“I’m sorry, we think you are really great, but I have to let you go.”

Confidence was high because employment was high, and consumers operate in a microcosm of their own environment.

“[Who is a better measure of economic strength?] Is it the consumer cranking out work hours, raising a family, and trying to make ends meet? Or the CEO of a company who is watching sales, prices, managing inventory, dealing with collections, paying bills, and managing changes to the economic landscape on a daily basis? A quick look at history shows this level of disparity (between consumer and CEO confidence) is not unusual. It happens every time prior to the onset of a recession.

Far From Over

Why is this important?

Hiring, training, and building a workforce is costly. Employment is the single largest expense of any business, but a strong base of employees is essential for the prosperity of a business. Employers do not like terminating employment as it is expensive to hire back and train new employees, and there is a loss of productivity during that process. Therefore, CEOs tend to hang onto employees for as long as possible until bottom-line profitability demands “leaning out the herd.”

The same process is true coming OUT of a recession. Companies are “lean and mean” and are uncertain about the actual strength of the recovery. Again, given the cost to hire and train employees, they tend to wait as long as possible to be certain of justifying the expense.

Simply, employers are slow to hire and slow to fire.

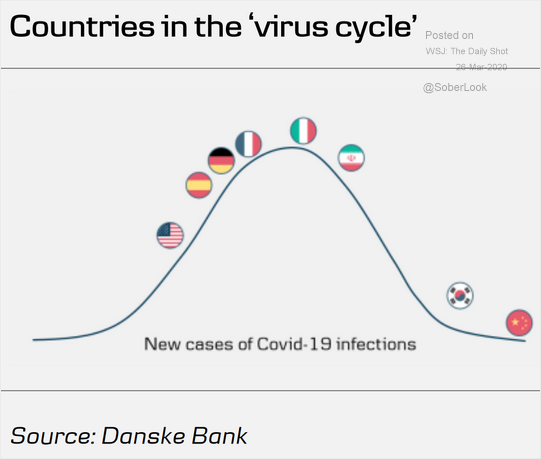

While there is much hope that the current “economic shutdown” will end quickly, we are still very early in the infection cycle relative to other countries. Importantly, we are substantially larger than most, and on a GDP basis, the damage will be worse.

What the cycle tells us is that jobless claims, unemployment, and economic growth are going to worsen materially over the next couple of quarters.

“But Lance, once the virus is over everything will bounce back.”

Maybe not.

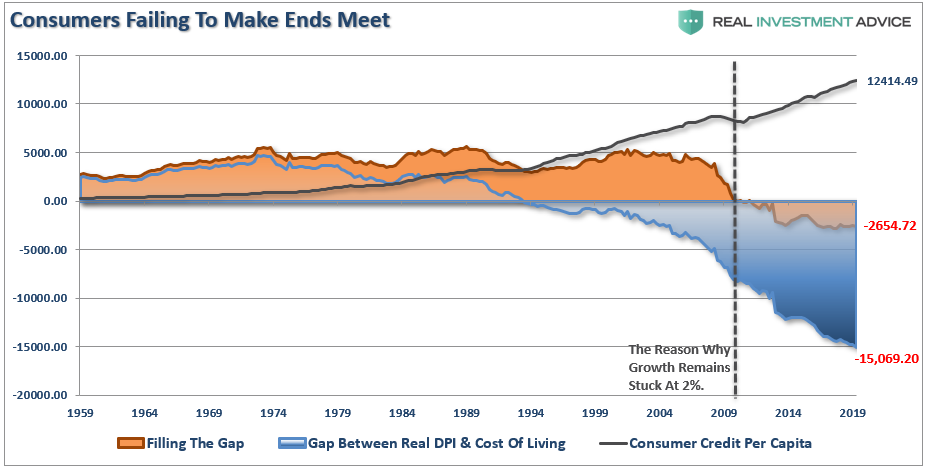

The problem with the current economic backdrop, and mounting job losses, is the vast majority of American’s were woefully unprepared for any type of disruption to their income going into recession. As discussed previously:

“The ‘gap’ between the ‘standard of living’ and real disposable incomes is shown below. Beginning in 1990, incomes alone were no longer able to meet the standard of living so consumers turned to debt to fill the ‘gap.’ However, following the ‘financial crisis,’ even the combined levels of income and debt no longer fill the gap. Currently, there is almost a $2654 annual deficit that cannot be filled.”

As job losses mount, a virtual spiral in the economy begins as reductions in spending put further pressures on corporate profitability. Lower profits lead to more unemployment, and lower asset prices until the cycle is complete.

While the virus may end, the disruption to the economy will last much longer, and be much deeper, than analysts currently expect. Moreover, where the economy is going to be hit the hardest, is a place where Federal Reserve actions have the least ability to help – the private sector.

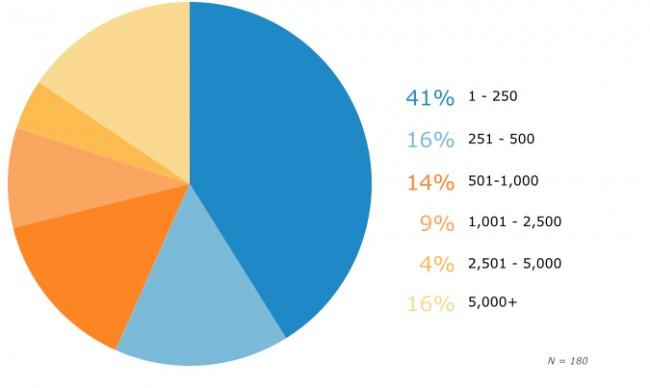

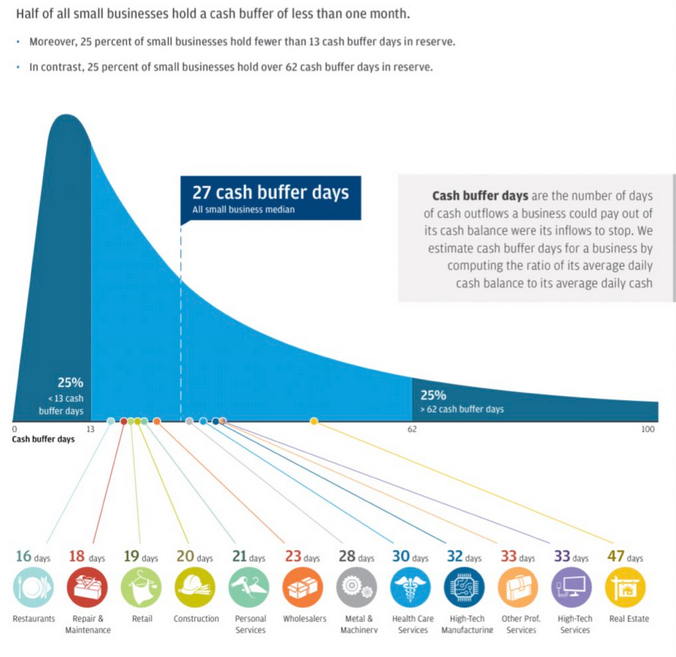

Currently, businesses with fewer than 500-employees comprise almost 60% of all employment. 70% of employment is centered around businesses with 1000-employees, or less. Most of the businesses are not publicly traded, don’t have access to Wall Street, or Federal Reserve’s bailouts.

The problem with the Government’s $2 Trillion fiscal stimulus bill is that while it provides one-time payments to taxpayers, which will do little to extinguish the financial hardships and debt defaults they will face.

Most importantly, as shown below, the majority of businesses will run out of money long before SBA loans, or financial assistance, can be provided. This will lead to higher, and a longer-duration of, unemployment.

One-Percenter

What does this all mean going forward?

The wealth gap is going to explode, demands for government assistance will skyrocket, and revenues coming into the government will plunge as trillions in debt issuance must be absorbed by the Federal Reserve.

While the top one-percent of the population will exit the recession relatively unscathed, again, it isn’t the one-percent I am talking about.

It’s economic growth.

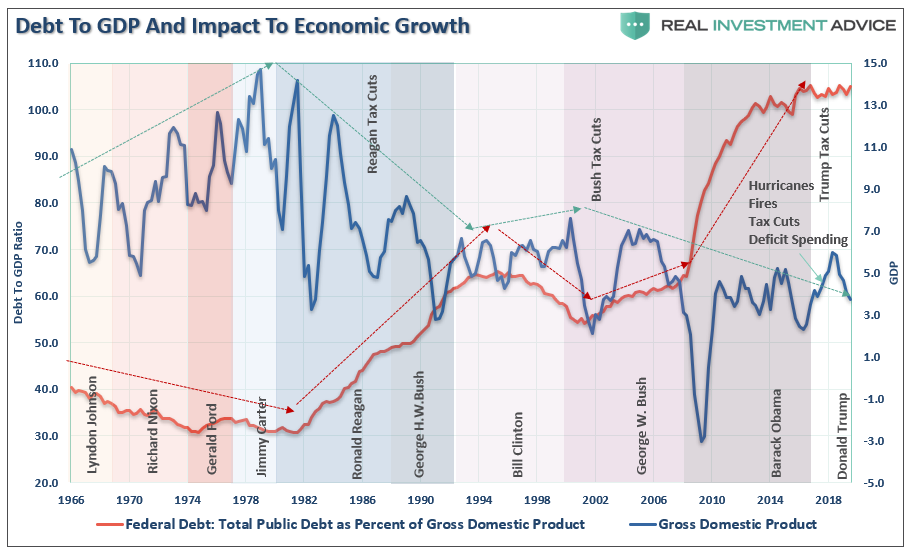

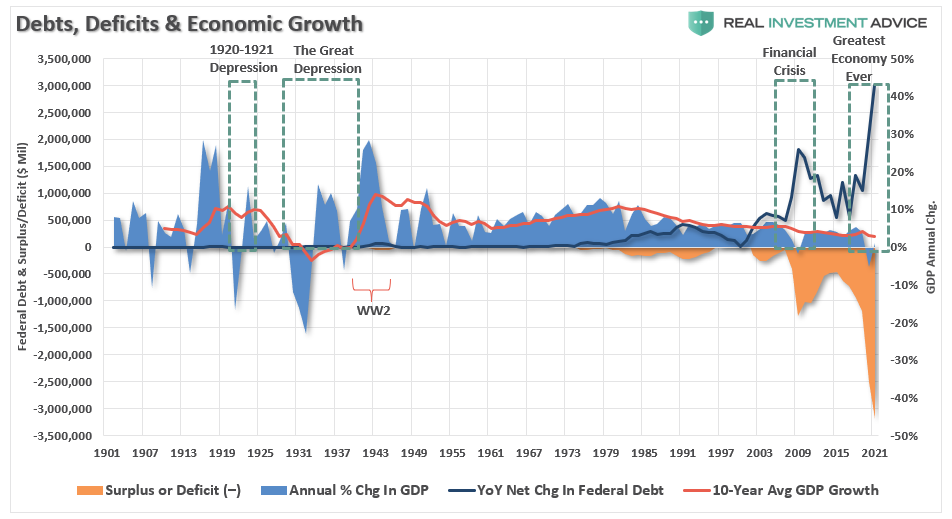

As discussed previously, there is a high correlation between debts, deficits, and economic prosperity. To wit:

“The relevance of debt growth versus economic growth is all too evident as shown below. Since 1980, the overall increase in debt has surged to levels that currently usurp the entirety of economic growth. With economic growth rates now at the lowest levels on record, the growth in debt continues to divert more tax dollars away from productive investments into the service of debt and social welfare.”

However, simply looking at Federal debt levels is misleading.

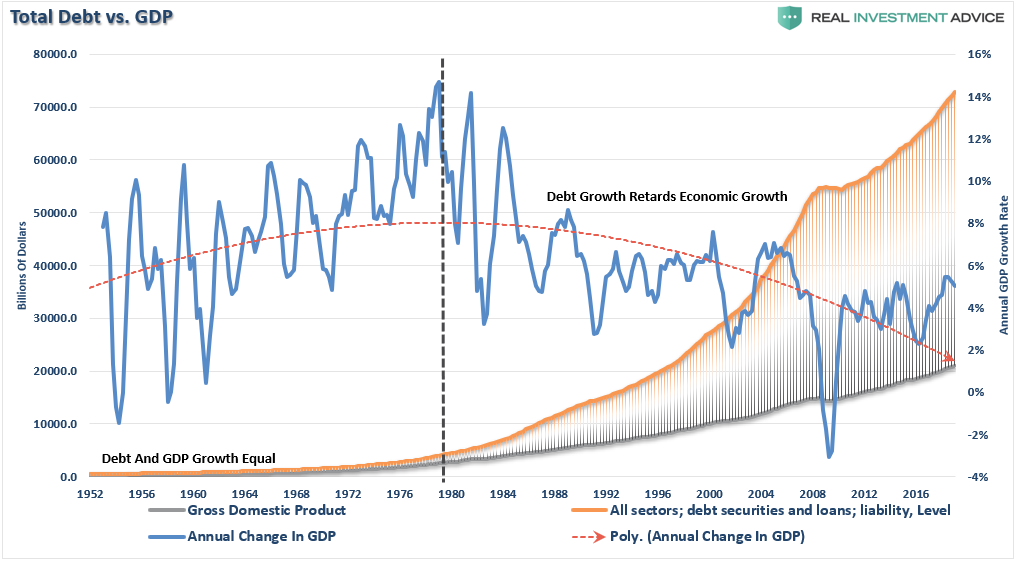

It is the total debt that weighs on the economy.

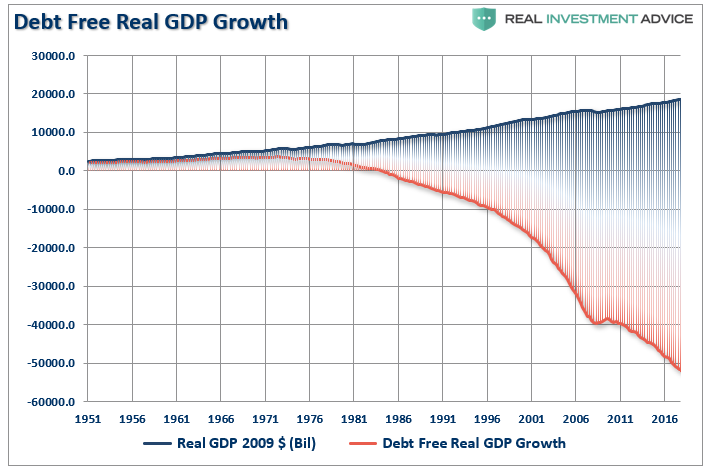

It now requires nearly $3.00 of debt to create $1 of economic growth. This will rise to more than $5.00 by the end of 2020 as debt surges to offset the collapse in economic growth. Another way to view the impact of debt on the economy is to look at what “debt-free” economic growth would be.

In other words, without debt, there has been no organic economic growth.

Notice that for the 30-year period from 1952 to 1982, the economic surplus fostered a rising economic growth rate, which averaged roughly 8% during that period. Since then, the economic deficit has only continued to erode economic prosperity.

Given the massive surge in the deficit that will come over the next year, economic growth will begin to run a long-term average of just one-percent. This is going to make it even more difficult for the vast majority of American’s to achieve sufficient levels of prosperity to foster strong growth. (I have estimated the growth of Federal debt, and deficits, through 2021)

The Debt End Game

The massive indulgence in debt has simply created a “credit-induced boom” which has now reached its inevitable conclusion. While the Federal Reserve believed that creating a “wealth effect” by suppressing interest rates to allow cheaper debt creation would repair the economic ills of the “Great Recession,” it only succeeded in creating an even bigger “debt bubble” a decade later.

“This unsustainable credit-sourced boom led to artificially stimulated borrowing, which pushed money into diminishing investment opportunities and widespread mal-investments. In 2007, we clearly saw it play out “real-time” in everything from sub-prime mortgages to derivative instruments, which were only for the purpose of milking the system of every potential penny regardless of the apparent underlying risk.”

In 2019, we saw it again in accelerated stock buybacks, low-quality debt issuance, debt-funded dividends, and speculative investments.

The debt bubble has now burst.

Here is the important point I made previously:

“When credit creation can no longer be sustained, the markets must clear the excesses before the next cycle can begin. It is only then, and must be allowed to happen, can resources be reallocated back towards more efficient uses. This is why all the efforts of Keynesian policies to stimulate growth in the economy have ultimately failed. Those fiscal and monetary policies, from TARP and QE, to tax cuts, only delay the clearing process. Ultimately, that delay only deepens the process when it begins.

The biggest risk in the coming recession is the potential depth of that clearing process.”

This is why the Federal Reserve is throwing the “kitchen sink” at the credit markets to try and forestall the clearing process.

If they are unsuccessful, which is a very real possibility, the U.S. will enter into a “Great Depression” rather than just a “severe recession,” as the system clears trillions in debt.

As I warned previously:

“While we do have the ability to choose our future path, taking action today would require more economic pain and sacrifice than elected politicians are willing to inflict upon their constituents. This is why throughout the entirety of history, every empire collapsed eventually collapsed under the weight of its debt.

Eventually, the opportunity to make tough choices for future prosperity will result in those choices being forced upon us.”

We will find out in a few months just how bad things will be.

But I am sure of one thing.

The Fed can’t fix what’s broken.

While the financial media is salivating over the recent bounce off the lows, here is something to think about.

-

Bull markets END when everything is as “good as it can get.”

-

Bear markets END when things simply can’t “get any worse.”

We aren’t there yet.

Tyler Durden

Sat, 03/28/2020 – 11:15