S&P Reaffirms US At AA+, Outlook Stable

With the US in deep economic and financial crisis, with the Fed now monetizing more than 100% of debt issuance, and with US debt set to hit $30 trillion from its current $23 trillion in about 2 years, there were growing concerns that this was an opportunity for a perfect storm to strike with one or more rating agencies downgrading the US as a result of the nation’s upcoming unprecedented surge in debt.

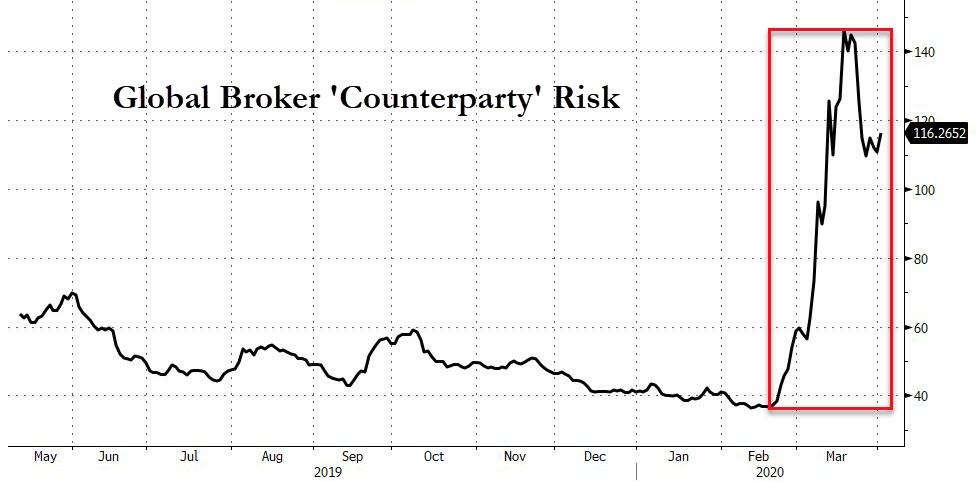

To be sure, US CDS had already started moving sharply higher, an indication that at least some traders – clearly not of the idiot MMT persuasion – were growing concerned about the country’s long-term viability.

However, the US won a much needed reprieve late on Thursday when perhaps still recalling the nightmare backlash to what happened in August 2011, when it downgraded the US from the pristine AAA to AA+ and the unprecedented attacks from Tim Geithner, S&P reaffirmed the US at AA+, outlook stable. So at least for now, the US credit rating is safe, even if the reserve status of the dollar is getting riskier by the day. In fact, it is no accident that in the S&P rating, the analyst explicitly singled out the dollar’s reserve currency state:

“Inherent economic and institutional strengths underpin the U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s premier reserve currency.”

We’ll see how much longer that lasts.

Key excerpts from the S&P rating below:

U.S. ‘AA+/A-1+’ Sovereign Ratings Affirmed; Outlook Remains Stable

Overview

The sovereign ratings on the U.S. reflect its diversified and resilient economy, extensive monetary policy flexibility, and unique status as the issuer of the world’s leading reserve currency.

The ratings are constrained by high general government debt and fiscal deficits, both of which are likely to worsen this year following the economic shock caused by the coronavirus pandemic, before moderating over the next three years.

We are affirming our ‘AA+/A-1+’ sovereign credit ratings on the U.S.

The outlook remains stable, reflecting our expectation that unprecedented fiscal and monetary stimulus will limit the economic downturn and set the stage for recovery in 2021.

Rating Action

On April 2, 2020, S&P Global Ratings affirmed its ‘AA+’ long-term and ‘A-1+’ short-term unsolicited sovereign credit ratings on the U.S. The outlook on the long-term rating remains stable. The transfer and convertibility assessment is unchanged at ‘AAA’.

Outlook

The stable outlook indicates our view that the negative and positive rating factors for the U.S. will be balanced over the next two years. We expect continued political disputes about the implementation of economic and other policies in the lead-up to national elections in November. However, we expect continuity in the recent economic measures aimed at mitigating the effects of the pandemic, regardless of the election outcome. We also expect the U.S.’s institutional checks and balances, strong rule of law, and free flow of information to support stability and predictability of economic policies. The U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s premier reserve currency, and the size and depth of the U.S. financial market, should sustain policy flexibility.

We expect economic recovery in 2021, which will partly compensate the loss of output this year, and continued GDP growth afterward. A recovering economy will lead to moderate fiscal improvement next year after a sharp rise in the fiscal deficit and sovereign debt burden in 2020. However, a larger and more prolonged deterioration in public finances beyond our current expectations, without positive signals of future corrective actions, could place pressure on the ratings, leading to a negative action.

On the other hand, we could raise the rating if we see signs of more effective and proactive public policymaking beyond the quick policy response to the current recession, which could reflect greater bipartisan coordination between the executive branch and Congress than has been the norm in recent years.

Rationale

The sovereign credit ratings on the U.S. are supported by:

- The wealth, resilience, and diversity of its economy;

- Its institutional strengths;

- Its extensive economic policy flexibility that includes a proactive monetary policy; and

- Its unique status as the issuer of the world’s leading reserve currency (the U.S. currency accounts for almost 60% of official exchange reserves held globally).

The institutional strength, independence, and credibility of the Federal Reserve System provides the U.S. with considerable monetary policy flexibility. The Federal Reserve has undertaken timely and forceful steps to restart quantitative easing, and set up various new lending facilities to support financial and nonfinancial corporations, municipal governments, money markets, and the commercial paper market, to help stabilize the economy. It has also reinstated swap lines with central banks around the world to provide dollar liquidity globally.

Disagreement across and within political parties has resulted in slower decision-making in normal times and has limited the government’s ability to enact forward-looking legislation, particularly for corrective fiscal policy. That, along with the government’s fiscal profile, including a high level of debt, constrains the ratings.

However, the rapid economic policy response to the coronavirus pandemic illustrates the ability of the U.S.’s governing institutions and political leadership to undertake timely and forceful measures during a crisis, as was also seen in 2008. Congress and the president quickly reached agreement on a massive fiscal stimulus on March 27, only eight weeks after the end of an impeachment trial of the president. The ability to respond forcefully to the economic challenge, amid intense partisanship during an election year, has shown that the checks and balances embedded in the U.S. political system, along with widespread distribution of power across branches of government and across levels of government, have been generally effective in maintaining stability and confidence.

Flexibility and performance profile: Strong monetary policy credibility and international reserve currency status provide flexibility to undertake massive countercyclical policies to stabilize the economy

- The U.S. dollar remains the premier international reserve currency.

- The credibility of the Federal Reserve system is unparalleled, supporting monetary flexibility.

- The recession will enlarge the fiscal deficit and boost the net general government debt burden toward 100% of GDP in 2020.

The U.S. is drawing upon its extraordinary monetary flexibility to combat the downturn as the Federal Reserve has acted quickly and forcefully. It has restarted quantitative easing by purchasing Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities with no announced caps. In addition, it has set up two new lending facilities–primary- and secondary-market corporate credit facilities–to support credit to large employers for new bond and loan issuance and to provide liquidity for outstanding corporate bonds, respectively.

It is also expanding its money market lending facility and opening its commercial paper funding facility to high-quality municipal debt, an important step to help stabilize public finances at the subnational level. The central bank has eased capital and regulatory restrictions and expanded repo lending. Moreover, it has entered into currency swap and repo arrangements with many other central banks to provide dollar funding to the global financial system.

Inherent economic and institutional strengths underpin the U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s premier reserve currency. This status affords the U.S. significant flexibility in its external accounts. We believe that the U.S. has unparalleled external liquidity, thanks to its key reserve currency status, as well as the degree to which it has supplied liquidity around the globe.

Our external analysis has been complicated by the dollar’s dominant reserve currency role. We expect the ratio of external debt (net of liquid assets) to current account receipts to hover near 320% in 2020-2022, which is high compared with the ratios of most sovereigns. However, the overall net external liability position of the U.S. is lower. In addition, the external debtor position may be overstated, considering currency issues, composition considerations, and the difficulty of recording multinational activity of U.S. private companies in offshore centers. Changes in valuation of the U.S.’s external assets and liabilities, including derivatives, outweigh the role of current account flows in measurements of the U.S.’s external stocks of assets and liabilities. The current account deficit was 2.3% of GDP in 2019 and is likely to be around 1%-2% in 2021-2022.

The combination of recession, higher government spending, and support for financial and nonfinancial enterprises will raise the fiscal deficit and the public sector’s debt burden. However, we expect economic recovery will lead to fiscal improvement after the near-term deterioration. The general government deficit may approach 16% of GDP in 2020, partly due to spending rising by more than 6 percentage points of GDP. We assume that economic recovery in 2021 will partly recoup some lost tax revenues, and that government spending will decline (as a share of GDP) from its peak levels, cutting the deficit below 8% of GDP. We expect the general government deficit will decline below 5% of GDP by 2022.

In our view, the net general government debt burden is likely to spike toward 100% of GDP in 2020, and stabilize around that level in coming years. Thereafter, its trajectory will depend on corrective revenue and spending reforms to counteract a potential deterioration partly due to demographic trends. Nonresidents hold about 40% of the debt (the largest held by Japan and China, which together account for 13% of total debt), down from a peak of 49% in 2012. The Federal Reserve Bank held about 15% of the total debt until recently, but it will hold more as part of its expansionary policy.

The total cost of fiscal measures (including potential added stimulus measures later this year) is difficult to estimate, given uncertainty about actual disbursements from the fiscal stimulus (which includes both direct spending and lending commitments) and about the losses in the financial system that ultimately are borne by the sovereign. We believe there will be bipartisan support for moderate corrective fiscal measures, despite challenging politics, after the upcoming national elections.

Our primary fiscal metric on the flow side is the change in net general government debt, which we expect to reach 16% of GDP in 2020 but decline toward 7% in 2021 and average 3.9% during 2022-2023. The change in debt results mostly from yearly central government deficits but also from off-budget activities, such as net lending. We expect the general government deficit (as stated in the National Income and Product Accounts on a calendar-year basis) to follow a similar trajectory. The change in net general government debt also includes items such as the increase in direct student loans.

The U.S. government has periodically reached its statutory debt ceiling (last time in March 2019) as Congress failed to either raise the debt limit or suspend it, forcing the Treasury to undertake extraordinary measures to remain within the debt limit while still meeting its legal obligations. Current law lifts the debt ceiling limit until mid-2021, after the elections later this year. Our ratings assume Congress will continue to raise or suspend the debt ceiling.

Our assessment of the U.S.’s debt position incorporates our view that contingent liabilities from the financial sector and all nonfinancial public enterprises are moderate. This assessment stems primarily from the materiality and systemic importance of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in light of their low capitalization. The credit standing of both entities incorporates our assessment of an almost certain likelihood of extraordinary support from the Treasury given their critical policy role in the housing sector and integral link with the government. With $5.7 trillion in assets as of December 2019, they are material in size (around 27% of GDP).

Tyler Durden

Thu, 04/02/2020 – 19:28