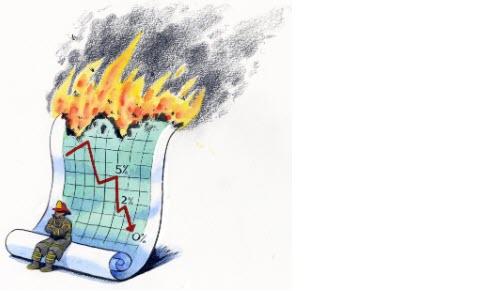

Jim Grant Warns The Fed “Firemen Are Also The Arsonists”

Having put put America straight on what we are facing and the consequences of these unelected and unaccountable officials terrifying experiments, Grant’s Interest Rate Observer editor Jim Grant is back with another warning that irresponsible policy from the Federal Reserve made the coronavirus crisis worse than it had to be.

As Grant notes, “it took a viral invasion to unmask the weakness of American finance.”

Distortion in the cost of credit is the not-so-remote cause of the raging fires at which the Federal Reserve continues to train its gushing liquidity hoses; but, as Grant exclaims, the firemen are also the arsonists echoing his earlier in the week comments that:

Jay Powell’s seemingly blinkered proclamation that “he sees no prospective consequences with regard the purchasing power of the dollar” as “very concerning” adding more pertinently that he thinks “that wilful ignorance is a clear-and-present-danger for creditors of The United States.”

It was the Fed’s suppression of borrowing costs, and its predictable willingness to cut short Wall Street’s occasional selling squalls, that compromised the U.S. economy’s financial integrity.

The coronavirus pandemic would have called forth a dramatic response from the central bank in any case. Not even the most conservatively financed economy could long endure an official order to cease and desist commercial activity. But frail corporate balance sheets and overextended markets go far to explain the immensity of the interventions.

Perhaps never before has corporate America carried more low-grade debt in relation to its earning power than it does today. And rarely have equity valuations topped the ones quoted only weeks ago.

“John Bull can stand many things, but he can’t stand 2%,” said Walter Bagehot, the Victorian-era editor of the Economist, concerning the negative side effects of a rock-bottom cost of capital. Needing income, investors will take imprudent risks to get it. And if 2% invites trouble, zero percent almost demands it.

Interest rates are the critical prices that measure investment risk and set the present value of estimated future cash flows. The lower the rates, other things being equal, the higher the prices of stocks, bonds and real estate—and the greater the risk of holding those richly priced assets.

In 2010 the Federal Reserve set out to lift market prices through a rate-suppression program called quantitative easing. Chairman Ben Bernanke was forthright about his intentions. “Easier financial conditions will promote economic growth,” he wrote at the time. Lower interest rates would make housing more affordable and business investment more desirable. Higher stock prices would “boost consumer wealth and help increase confidence, which can also spur spending.” The Fed commandeered investment values into the government’s service. It seeded bull markets in the public interest.

But investment valuations don’t exist to serve a public-policy agenda. Their purpose is to allocate capital. Distort those values and you waste not only money but also time – human heartbeats.

Like a shark, credit must keep moving. Loans fall due and must be repaid or rolled over (or, in extremis, defaulted on). When the economy stops, as the world’s has effectively done, lenders are likely to demand the cash that not every borrower can produce.

To resolve the devastating panic of 1825, the Bank of England rendered “every assistance in our power,” as a director of the bank testified, “and we were not upon some occasions over nice.”

In a still more radical vein, the Fed has set about buying (or supporting the purchase of) commercial paper, residential mortgage-backed securities, Treasurys, investment-grade corporate bonds, commercial mortgage-backed securities and asset-backed securities. It has abolished bank reserve requirements. Through a new direct-lending program, the Fed has become a kind of commercial bank.

If not for the buildup of the financial excesses of the past 10 years, fewer such monetary kitchen sinks would likely have had to be deployed. No pandemic explains the central bank’s massive infusions into the so-called repo market that followed this past September’s unscripted spike in borrowing costs. For still obscure reasons, a banking system that apparently is more than adequately capitalized was unable to meet a sudden demand for funds on behalf of the dealers who warehouse immense portfolios of government debt.

The superabundance of Treasury securities is the spoor of America’s trillion-dollar boom-time deficits. Persistently low interest rates have facilitated that borrowing, as they have the growth of private-equity investing (ordinarily with lots of leverage), the rise of profitless startups, the raft of corporate share repurchases, and the unnatural solvency of loss-making companies that have funded themselves in the Fed’s most obliging debt markets.

For savers in general, and the managers of public pension funds in particular, lawn-level interest rates confer no similar gains. On the contrary: To earn $50,000 in annual interest at a 5% government bond yield requires $1 million of capital; to earn the same income at a 1% yield demands $5 million of capital. To try to circumvent that forbidding arithmetic, income-famished investors buy stocks, junk bonds, real estate, what have you. It worked as long as the bubble inflated.

In a bubble, performance is the name of the investment game. Over the past 10 years, skeptics of our debt-financed prosperity have had to fall in line. To keep up with the Joneses, fiduciaries have sought an edge in lower-quality assets. Managers of investment-grade bond portfolios dabbled in junk bonds. Junk-bond investors slummed it in lower-rated junk or in the kind of bank debt that is senior in name but structured without the once-standard protective legal fine print.

Investing at positive nominal yields, Americans are still comparatively lucky. The holders of some $10.9 trillion of yen-, euro- and Swiss franc-denominated bonds are paying for the privilege of lending. “Investors seeking safety were prepared to face a guaranteed loss when holding the debt to maturity,” was how the Financial Times last summer tried to explain the nearly inexplicable.

Negative nominal bond yields are a 4,000-year first, according to Sidney Homer’s “A History of Interest Rates,” republished for a fourth edition with co-author Richard Sylla in 2005. Topsy-turvy investment-grade bond markets aren’t without precedent, but the extent of the upheaval today is startling. If adversity is the test of the quality of a senior security, as old-time doctrine held, segments of today’s corporate bonds and tradable bank loans have already flunked. On March 20, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence, the volume of such loans quoted below 80 cents on the dollar topped the peak distress level of 2008. While the panic subsequently abated, many supposedly senior corporate claims are proving to be fair-weather investments, not so different from common equity.

Deceived by ultralow interest rates, Americans borrow and lend in the kind of false economy that candidate Donald Trump properly condemned in 2016. Covid-19 will sooner or later beat a retreat. For the sake of honest prices and true values, it would be well if the central bankers did the same.

Simply put, Grant concludes, credit and equity markets “have become administered government-set indicators, rather than sensitive- and information-rich prices… and we are paying the price for that through the misallocation of resources.”

Grant ends on a hanging chad of a rhetorical question “what do corrections correct? Is there no salutary role for recessions and bear markets?”

Of course there is, he answers, “they separate the sound from the unsound, they separate the well-financed from the over-leveraged and if we never have these episodes of economic pain, we will be much the worse for it.”

Tyler Durden

Fri, 04/03/2020 – 19:20