Why Jeremy Siegel Is Wrong About End Of Bond Bull Market

Tyler Durden

Sat, 05/16/2020 – 12:30

Authored by Lance Roberts via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

Wharton’s Jeremy Siegel recently declared the end to the 40-year bond bull market.

“History has shown that somewhere this liquidity has to come out, and we’re not going to get a free lunch out of this. I think ultimately, it’s going to be the bond holder that’s going to suffer. That’s certainly not the popular notion right now.”

Such has been the same message from bond bears since the “Financial Crisis.” Yet, during the entirety of the past decade, rates have consistently headed lower.

The reasons have been clear, and since June of 2013, I have been pushing back against calls for higher rates from the likes of Bill Gross and Jeffrey Gundlach. While there have certainly been upticks in rates, as nothing travels in a straight line, the long-term trend remains lower.

Economic Growth Drives Rates

As noted by Jeremy Siegel, the primary argument for why rates must go up, is because rates are low.

“Forty years of a bull market in bonds. It’s really hard to turn your head around, and say could this be a turning point? But I think history will say yes. I see rates rising continuously over the next several years.”

The problem, however, is that interest rates are vastly different than equities. When people go to make a purchase on credit, borrow money for a house, or get a loan for a new car, they “buy payments.” What ultimately drives the purchase decision is “how much will this cost me?”

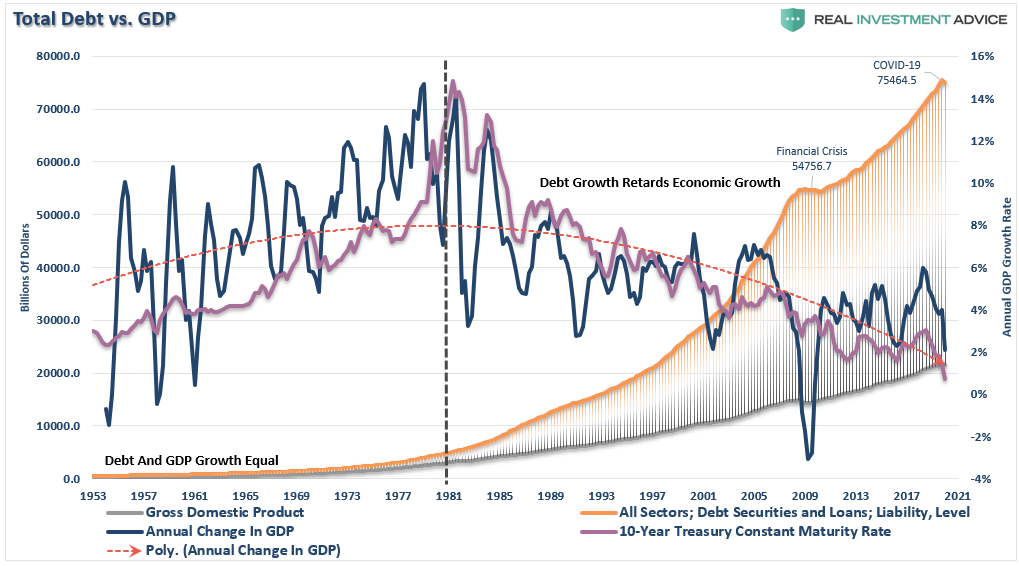

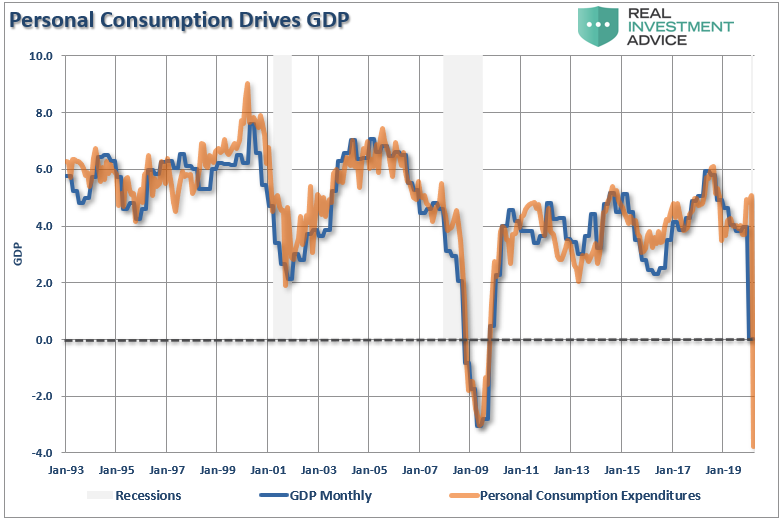

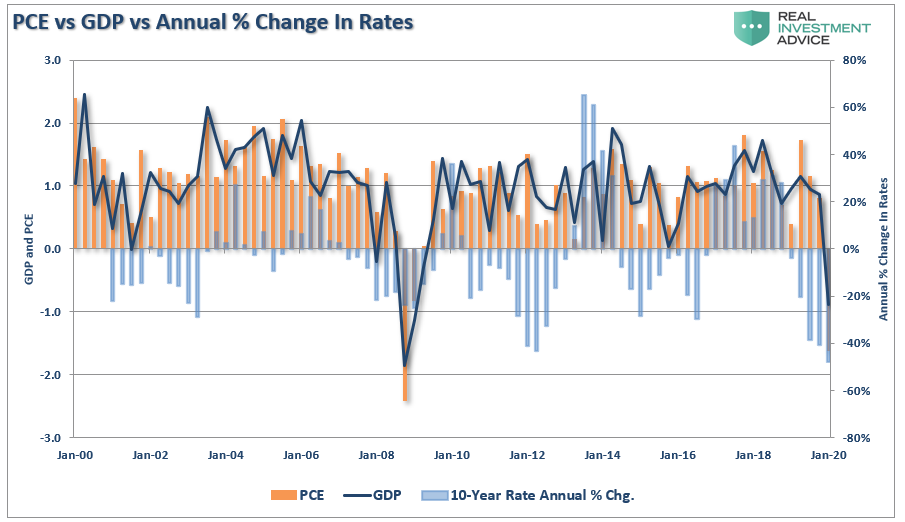

The determining factor in the purchase decision is the interest rate effect on the loan payment. If interest rates rise too much, consumption stalls. As consumption makes up 70% of GDP, one should not ignore the relationship between rates and consumption. As noted previously:

“There is a precise correlation between PCE and GDP. Not surprisingly, if consumption contracts due to high levels of unemployment, then economic growth declines.”

The trend and level of interests are the single best indicator of economic activity. As shown below, the rise and fall of rates correlates to the ebb and flow of the economy. When rising interest rates become constrictive on consumption, economic activity falls, pulling rates lower with it.

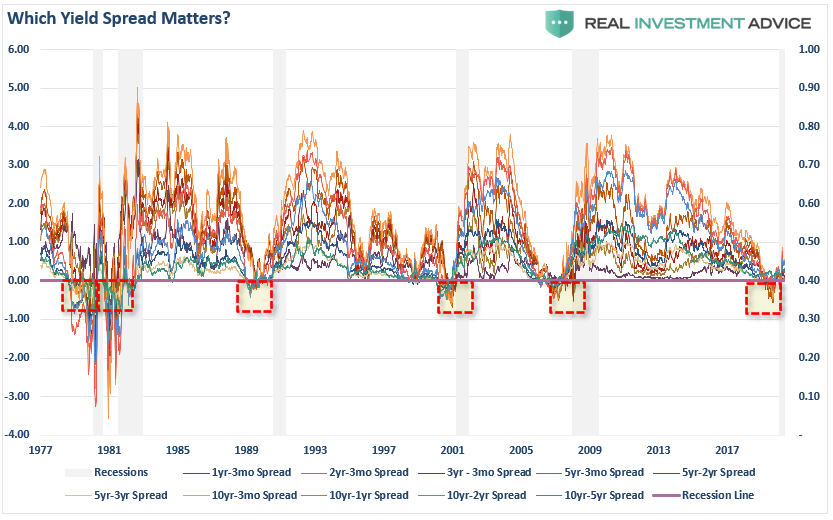

Such is why yield spreads are vital in determining the recessionary risks in the economy. As the yield spread flattens, it is reflective of economic weakness and diminishing demand for credit. As noted last year, it isn’t the “inversion” of the yield curve, which signals recession, it is the subsequent steepening.

In other words, “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Long-Term History

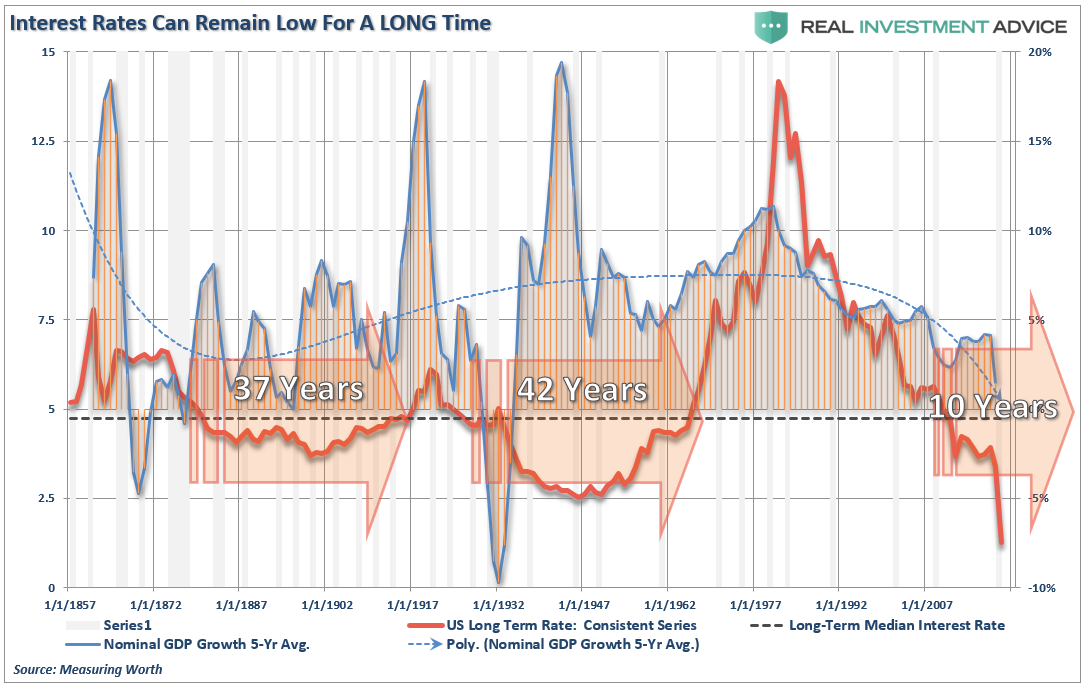

The chart below is a history of long-term interest rates going back to 1857. The dashed black line is the median interest rate during the entire period. I have compared interest rates to the 5-year nominal GDP growth rate over the same period.

(Note: As shown, interest rates can remain low for a VERY long time.)

Interest rates are a function of healthy, organic, economic growth that leads to rising demand for capital over time. There have been two previous periods in history which have been supportive of rising interest rates.

The first was during the turn of the previous century as the country became more accessible via railroads and automobiles.Manufacturing increased as World War I began, and America began shifting from an agricultural to an industrial one.

The second period followed World War II as America became the “last man standing.” After the war, France, England, Russia, Germany, Poland, Japan, and others were left devastated. It was here that America found its strongest run of economic growth in its history as the “boys of war” returned home to start rebuilding a war-ravaged Europe.

But that was just the start of it.

In the late ’50s, America embarked upon its greatest quest in human history as humankind took its first steps into space. The space race, which lasted nearly two decades, led to leaps in innovation and technology that paved the wave for the future of America.

These advances, combined with the industrial and manufacturing backdrop, fostered high levels of economic growth, increased savings rates, and capital investment, which provided support for higher interest rates.

The Structural Shift

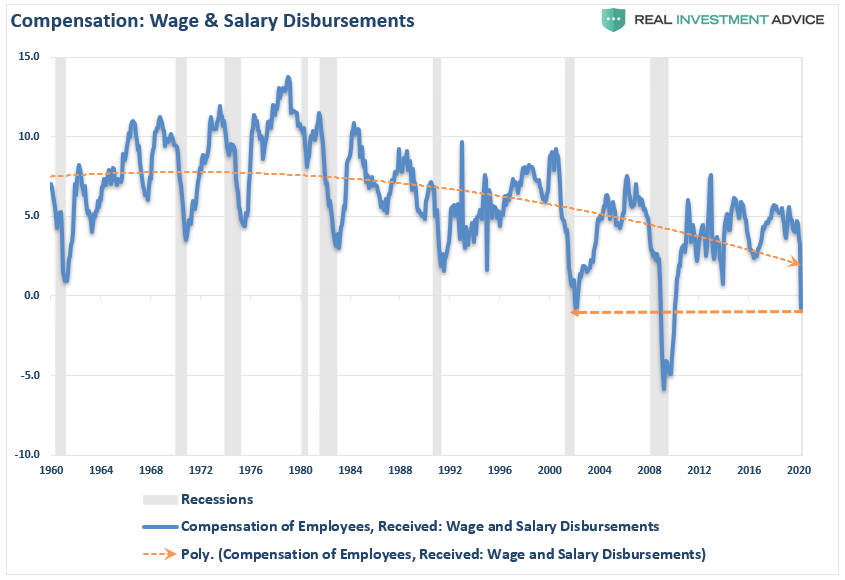

Currently, the U.S. is no longer the manufacturing powerhouse it once was, and globalization has sent jobs to the cheapest sources of labor. Technological advances continue to reduce the need for human labor, which suppresses wages as productivity increases.

The number of workers between the ages of 16 and 54 is at the lowest level relative to that age group since the late ’70s. That is a structural and demographic problem that continues to drag on economic growth. Such won’t change soon, with nearly 1/4th of the American population now permanently dependent on some form of governmental assistance.

This structural employment problem remains the primary driver as to why “everybody” is still wrong in expecting rates to rise.

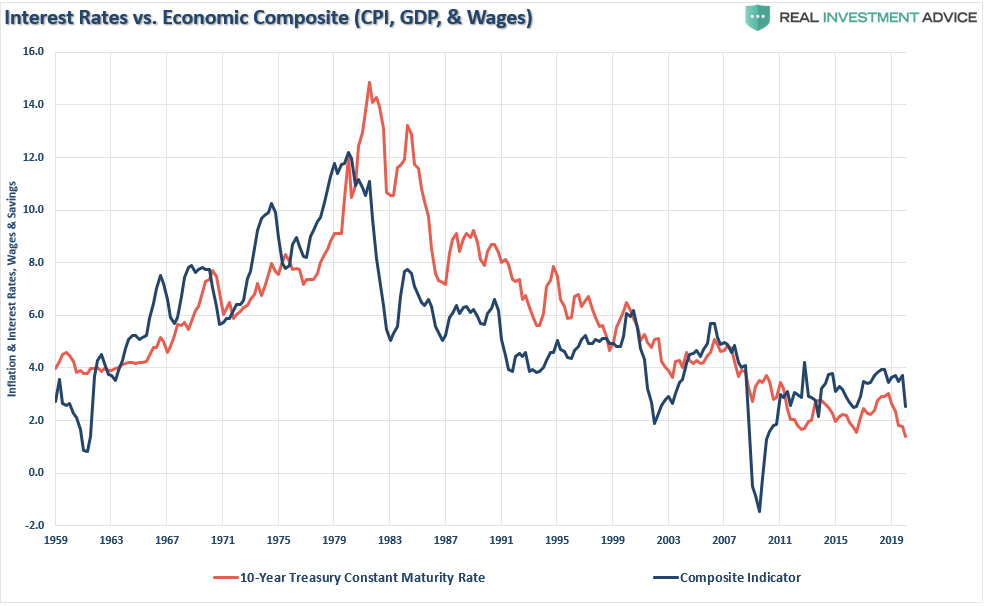

The high correlation between the three major components of our economic composite (inflation, economic and wage growth) and the level of interest rates is not surprising. Interest rates are not just a function of the investment market, but rather the level of “demand” for capital in the economy.

When the economy is expanding organically, the demand for capital rises as businesses increase production to meet rising demand. Increased production leads to higher wages, which in turn fosters more aggregate demand. As consumption increases, so does the ability for producers to charge higher prices (inflation) and for lenders to increase borrowing costs.

(Currently, we do not have the type of inflation that leads to more robust economic growth, just increases in the costs of living that saps consumer spending – Rent, Insurance, Health Care)

Low Demand For Capital

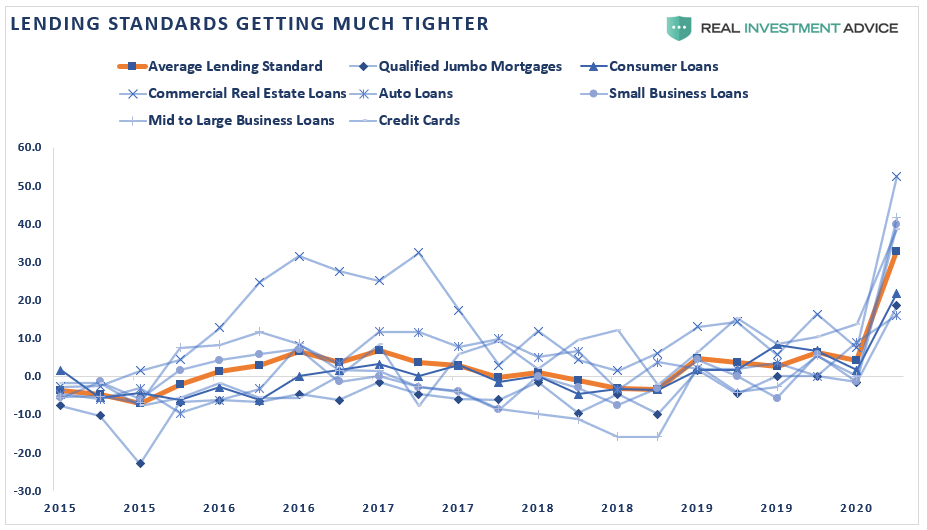

In the current economic environment, the need for capital remains low, outside of what is needed to absorb incremental demand. The impact on the economy from record levels of unemployment will have a wide range of impacts, which will forestall an economic recovery.

The profound suppression of wage growth from job losses will greatly reduce the demand for credit. Consumers’ focus will turn from a “want” to finance autos, durable goods, and houses, to the “need” to survive.

Simultaneously, the demand for credit is colliding with a lack of desire to “issue” credit. With reduced incomes, it is not only harder to make ends meet, but also harder to obtain additional credit. Given consumers are dependent upon credit to “fill the gap,” and with banks tightening lending standards, access to credit becomes more difficult.

Importantly, the majority of the job losses came from the very same areas that produced the most job “gains” in recent years. Those were the lower wage paying and temporary jobs in healthcare, leisure, and retail, which do not foster higher levels of consumption.

Currently, there are few economic tailwinds prevalent that could sustain a move higher in interest rates. The reason is simple. Higher interest rates reduce the flow of capital within the economy.

The Implications Of A Bond Bear

If there is indeed a bond bubble, a burst would mean bonds decline rapidly in price, pushing interest rates markedly higher. Such is the worst thing that could happen.

1) The Federal Reserve has been buying bonds for the last decade and has now moved into permanent “QE.” The recovery in economic growth remains dependent on massive levels of domestic and global interventions. Sharply rising rates will immediately curtail that growth as rising borrowing costs slows consumption.

2) The Fed currently runs the world’s largest hedge fund with over $6 Trillion in assets. Long Term Capital Mgmt., which managed only $100 billion, nearly crashed the economy when rising rates caused it to collapse. The Fed is 60x that size.

3) Rising rates will immediately kill the housing market. People buy payments, not houses, and rising rates mean higher payments.

4) An increase in rates means higher borrowing costs that leads to lower profit margins for corporations. Such will negatively impact the stock market as capital investment, buybacks, and debt issuance for M&A declines.

5) One of the main arguments of stock bulls over the last 10-years has been the stocks are cheap based on low-interest rates. When rates increase, the market becomes quickly overvalued.

6) The massive derivatives market will trigger another credit crisis as rate spread derivatives go bust.

7) As rates increase, so does the variable rate interest payments on credit cards.

8) Rising defaults on debt service will negatively impact banks, which are still not adequately capitalized and burdened by large levels of bad debts.

9) Commodities, which are sensitive to the global economy’s direction and strength, will plunge in price as the current recession extends.

10) The deficit/GDP ratio, which is already surging, will escalate as borrowing costs rise sharply. The many forecasts for lower future deficits will crumble as new estimates propel higher.

I could go on, but you get the idea.

The Japan Syndrome

The problem with most of the forecasts for the end of the bond bubble is the assumption that we are only talking about the isolated case of a shifting of asset classes between stocks and bonds. However, the issue of rising borrowing costs spreads through the entire financial ecosystem like a virus. The rise and fall of stock prices have very little to do with the average American and their participation in the domestic economy. Interest rates, however, are an entirely different matter.

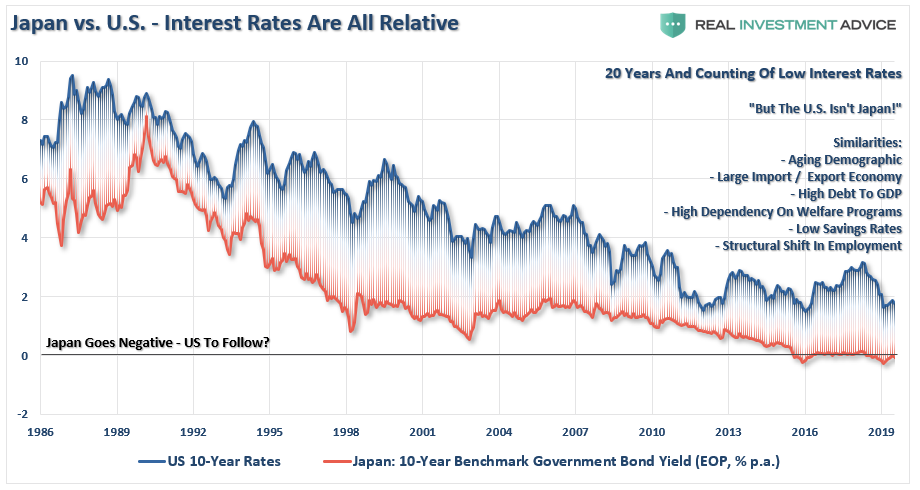

I won’t argue there is not much room for interest rates to fall in the current environment; there is also not much tolerance for increases. Since interest rates affect “payments,” increases in rates quickly have negative impacts on consumption, housing, and investment. This idea suggests is that there is one other possibility that the majority of analysts and economists ignore, which I call the “Japan Syndrome.”

Like Japan, the U.S. is caught in an ongoing ‘liquidity trap’ where maintaining ultra-low interest rates is the key to sustaining an economic pulse. As we are witnessing in the U.S., the unintended consequence of such actions is the battle with deflationary pressures. The lower interest rates go – the less return the economy can generate. An ultra-low interest rate environment, contrary to mainstream thought, has negative impacts on productive investments, and risk begins to outweigh the potential return.

As shown in the chart below, interest rates are relative globally. Rates can’t increase in one country while a majority of economies are pushing negative rates. As has been the case over the last 30-years, so goes Japan, so goes the U.S.”

Conclusion

Japan is has been fighting many of the same issues for the past two decades. The “Japan Syndrome” suggests that while interest rates are near lows, it is more likely to reflect the real levels of economic growth, inflation, and wages.

If that is true, then rates are most likely “fairly valued,” which implies that the U.S. could remain trapped within the current trading range for years as the economy continues to “muddle” along.

Jeremy Siegel, in time, will likely be proved wrong about the end of the “40-year bond bull” market. History suggests that not only is the “bond bull” alive and well, it likely has quite a long way as the U.S. become more like Japan over time.