Goldman: The Default Cycle Has Started

Tyler Durden

Mon, 05/25/2020 – 17:26

Perhaps inspired by our recent articles showing that “Loan Defaults Hit 6 Years High” and “Bankruptcy Tsunami Begins: Thousands Of Default Notices Are “Flying Out The Door“, Goldman writes this morning that with businesses shuttered and job losses mounting rapidly, “there is growing concern over the ability of borrowers to service their debt obligations and the resulting risks to financial stability.”

In response, Goldman “assesses the likely scale of economy-wide credit losses, the exposure of creditors to those losses, and the potential risks to financial stability and the banking sector” to conclude that “rising bankruptcies and delinquencies suggest the default cycle has started.”

How did Goldman get to that assessment?

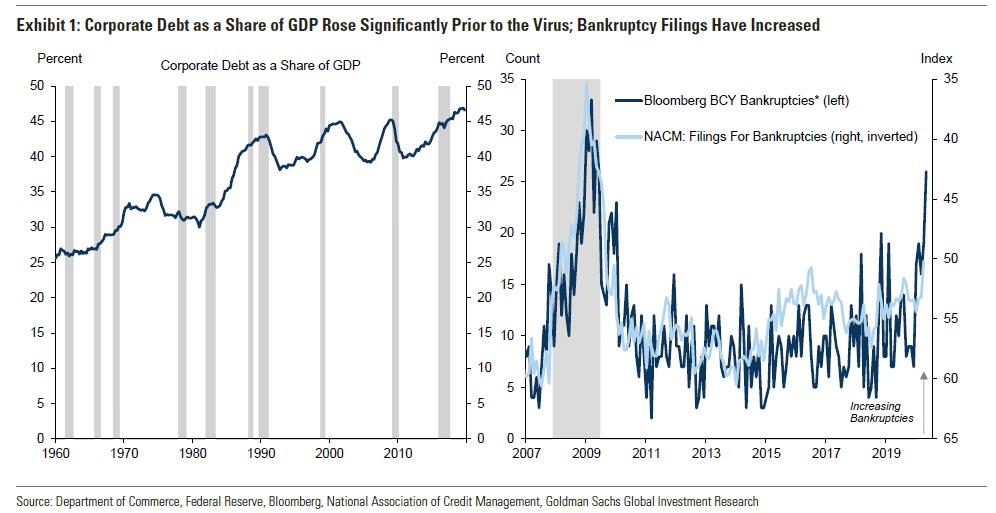

Looking at corporate credit, the bank first looked at corporate debt, noting that nonfinancial corporate debt grew by over 60% since 2011 and recently rose to an all-time high as a share of GDP (Exhibit 1, left), leading to growing concern even prior to the virus that corporate defaults could rise dramatically in the next downturn. Meanwhile, the sharp decline in revenues across many industries has left a large share of companies with negative cash flow, and rising bankruptcy filings and cases suggest the corporate default cycle has started.

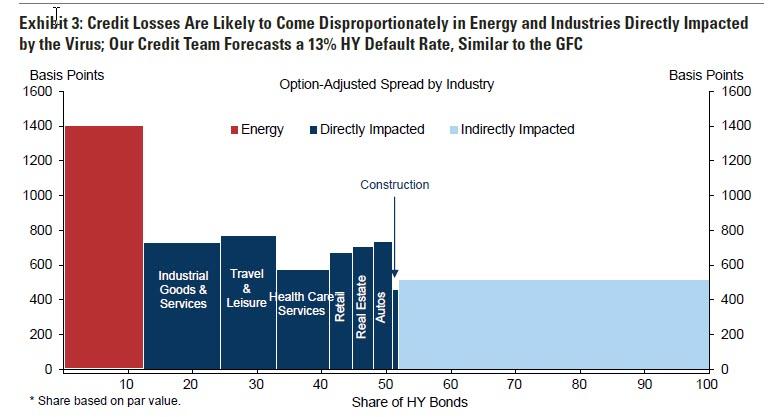

Unlike the financial crisis, the bank finds that a unique feature of this downturn “is the wide variation in industry exposure to the virus, with physical constraints on spending, occupational health risks, and geographical variation in the virus outbreak affecting industries differently.”

Goldman then performs an analysis of which industries are most impacted by credit losses due to the coronacrisis, and summarizes the findings in the next chart, which shows a coarser breakdown of virus-impacted industries, as well as their market share in the high-yield corporate bond space.

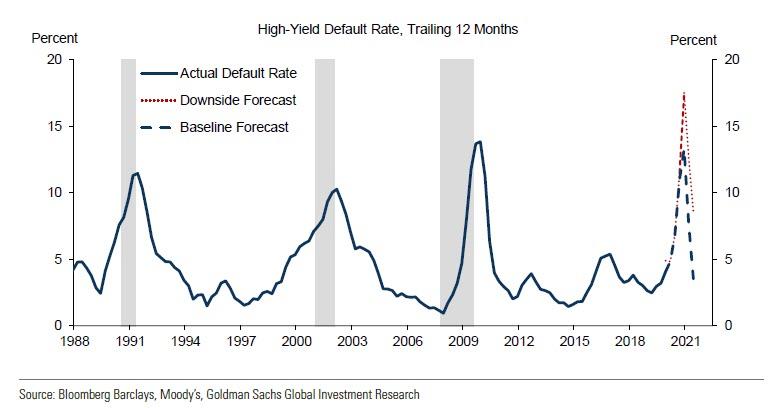

The energy sector stands out both in terms of its size and default risks, given the collapse in oil demand, its disproportionately large footprint in the corporate bond market relative to its GDP share, and the heavy amounts of leverage in the sector. Roughly half of high-yield corporate bonds are in the energy or virus-impacted industries, according to Goldman which adds that its credit strategists “estimate that the 12-month trailing high-yield default rate will increase to 13% by the end of 2020, similar to the peak rate reached during the Global Financial Crisis (Exhibit 3, bottom).”

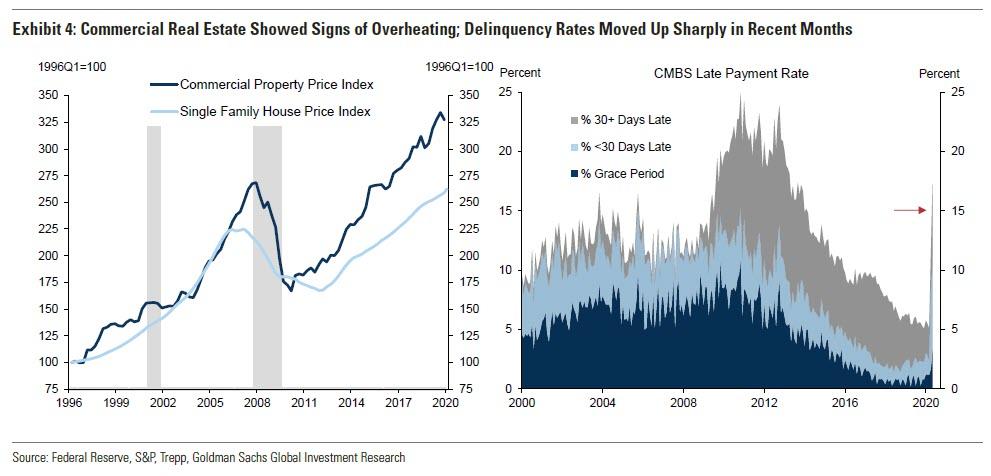

In addition to energy debt, another key area of concern – as we have repeatedly pounded the table in recent weeks – is commercial real estate (CRE), given signs of overheating and overstretched valuations prior to the virus, as well as the unprecedented declines in demand in industries such as lodging, healthcare, and retail.

Commercial real estate prices have outpaced single family house prices since the prior downturn (chart below, left), with CRE capitalization rates falling to historically low levels. Late payments on commercial mortgages have picked up sharply in recent months, suggesting mounting pressures (chart below, right).

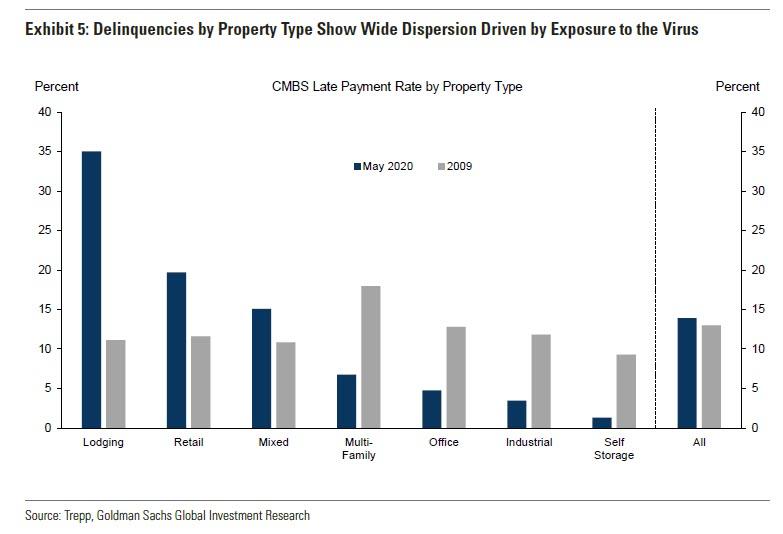

Tangentially, and as also discussed here extensively before, the unique nature of this downturn suggests that “variation in virus exposure will play a large role in determining the breadth and depth of credit losses in commercial real estate.” Delinquencies by property type already show wide dispersion, with virus-exposed property types such as lodging and retail showing much higher delinquency rates than less exposed property types such as self-storage. This contrasts with the prior real estate bust, when delinquencies were roughly evenly distributed across property types.

Overall, Goldman expects a deeper contraction of property incomes than during the financial crisis period, given the heavy stresses to rents and occupancy rates facing many properties, and overall losses on commercial mortgages similar to those observed during the financial crisis.

Meanwhile, even as consumers have been slow to telegraph stress, kept afloat thanks to hundreds of billions in transfer payments, significant downside risks to household debt also remain, particularly if unemployment insurance benefits are not extended, and if higher out-of-pocket medical expenses due to loss of employer-based health insurance push more households to default.

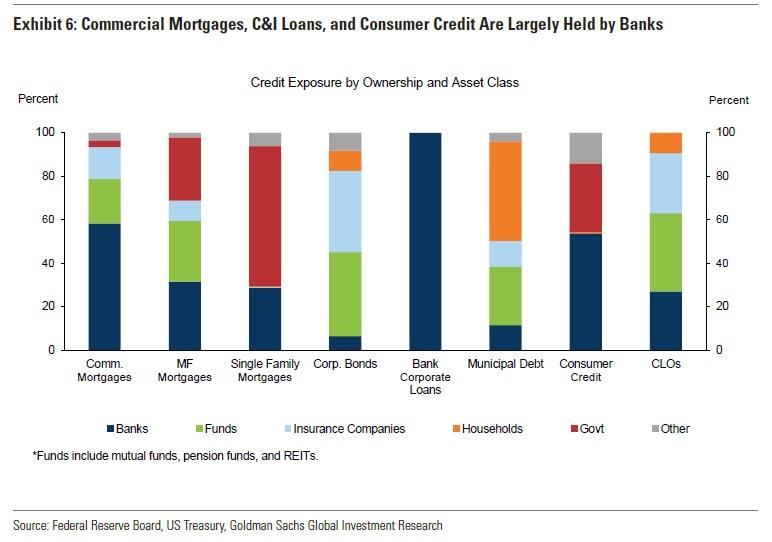

Who Will Bear The Losses

We next look to see where credit losses are most likely to be felt. The Fed’s Financial Accounts suggests that the banking system plays a large role in providing credit for commercial real estate and overall corporate borrowing, two areas of greater concern. Household debt is also largely held by banks, particularly residential mortgages, credit card loans, and auto loans, while student debt is largely held by the federal government.

Municipal debt, another area of concern, is largely held by households, mutual funds and pensions funds, and insurance companies, and thus likely poses a smaller threat to financial stability. Lastly, a growing share of corporate lending—especially in riskier categories, such as leveraged loans—is now done by nonbank financial institutions, including collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), asset managers, hedge funds, and private equity companies, and such lending is not well captured in the Fed’s Financial Accounts. TIC data provides some evidence that non-bank financial institutions and insurance companies own much of US CLO securities, a growing area of concern. Crucially, CLOs do not generally permit early redemptions and are thus less susceptible to runs, which is why Goldman strategists do not see CLOs posing a major risk to financial stability, “despite the likely significant pickup in defaults on leveraged loans.”

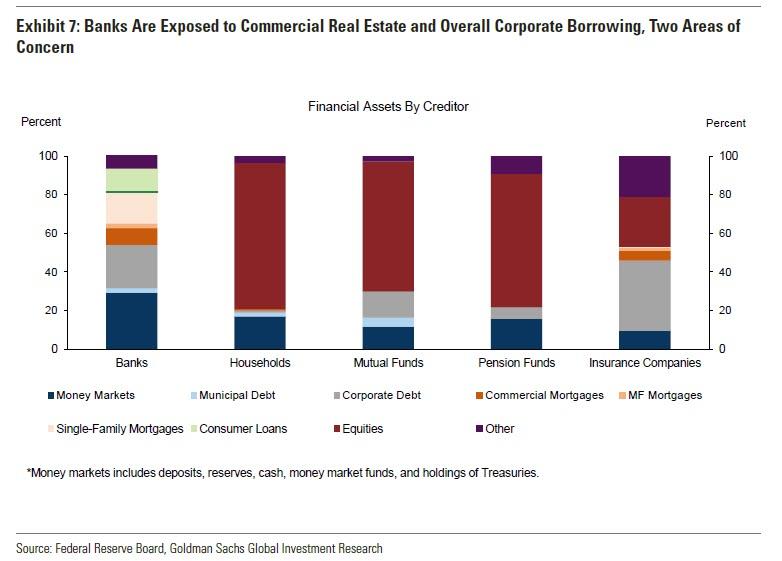

The next chart shows a breakdown of financial asset holdings by creditor, excluding financial institutions such as hedge funds and private equity companies where data is less readily available. Banks are highly exposed to many areas of credit, while households, mutual funds, and pensions are largely more exposed to equities. Insurance companies are somewhere in between, and hold a significant amount of exposure to corporate debt, including CLOs.

The bottom line is simple: contrary to conventional wisdom that banks are now far, far safer than they were during the financial crisis, they bear the broadest exposure to the coming default wave which will soon test just how safe they are.

Risks to the Banking System

As Goldman reminds us, the Fed’s Financial Stability Report warned that financial sector vulnerabilities including for the banking sector, are likely to be significant in the near term, while the April FOMC minutes indicated concern that banks could come under greater stress, particularly if more adverse economic scenarios were realized. The Fed’s Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey (SLOOS) indicated that lending standards tightened significantly, particularly for commercial and industrial (C&I) and CRE loans, with most banks citing a less favorable or more uncertain economic outlook, as well as a reduced tolerance for risk, as reasons for tightening lending standards. Loan loss provisions across banks have increased significantly in preparation for the rise in defaults and delinquencies.

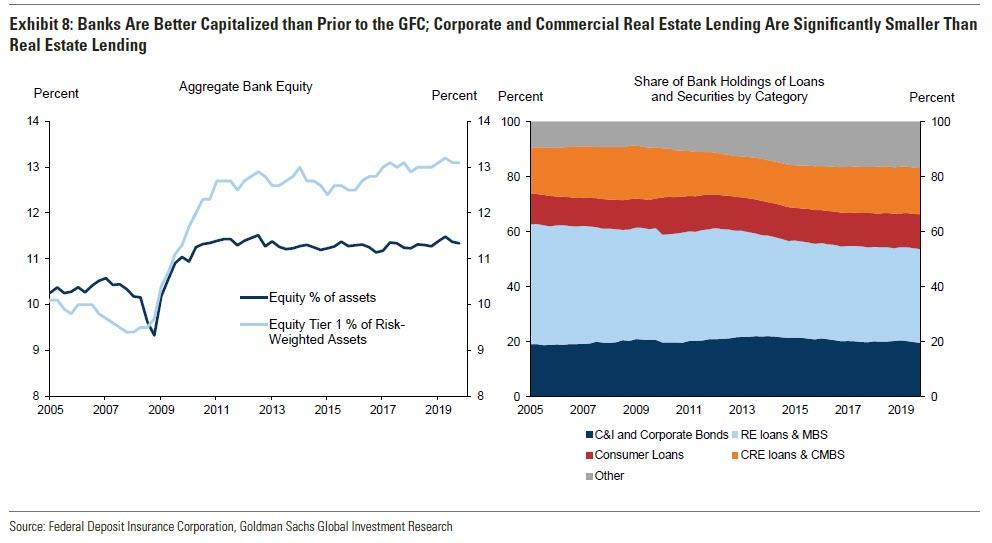

Curiously, only a modest percentage of banks cited a deterioration in their capital position as playing a role in tightening lending standards in the first quarter. In addition, residential real estate remains the largest category of lending in the banking system by a significant margin. And while Goldman believes that given that this downturn was not precipitated by a housing crisis, losses on this particularly large category will likely be smaller than during the GFC, the question of how quickly consumer cash flows return to normal will be critical in answering just how significant residential losses will be in a few months time.

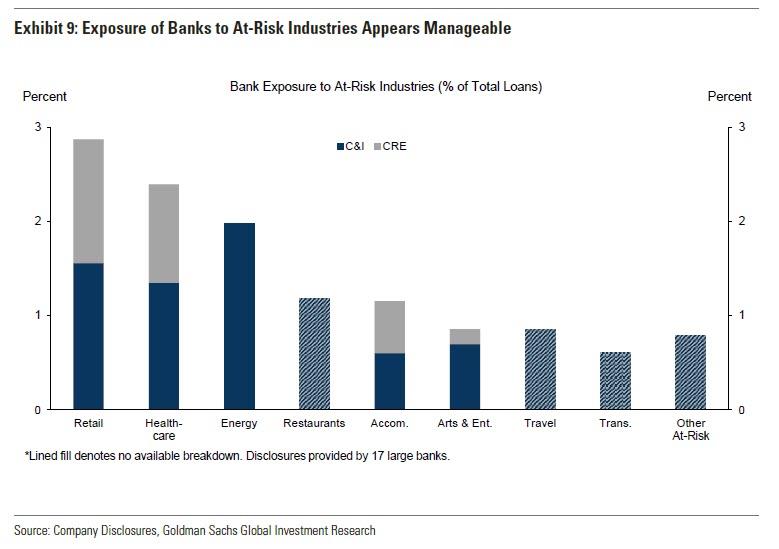

That said, one clear worry is that certain industries are heavily exposed to the virus, which may lead to larger risks to the banking system if the lending of particular banks, or the banking system as a whole, is highly concentrated in these industries.

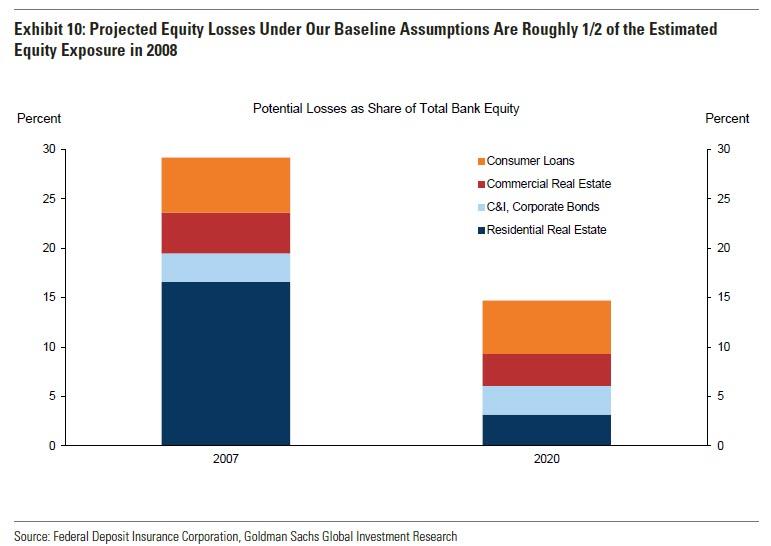

Next, Goldman assesses the vulnerability of bank balance sheets as of 2019 Q4, and estimates the losses on total bank equity from losses across asset categories. The bank assumes similar losses on C&I and CRE lending as in the 2008 crisis, but a smaller hit on residential mortgages and consumer loans (this may be a costly mistake). The bank then calculates the estimated losses as a percent of total bank equity capital, estimating that losses on C&I, CRE, consumer, and residential real estate loans would amount to roughly 15% of total bank equity, compared to around 30% of total bank equity at risk heading into the Global Financial Crisis, using ex-post realized losses across the same categories. Two main reasons account for this difference: first, losses on the large residential real estate category are likely to be smaller, and second, bank equity levels are higher today than before the crisis. Once again, these optimistic assumptions may end up having to be substantially revised higher.

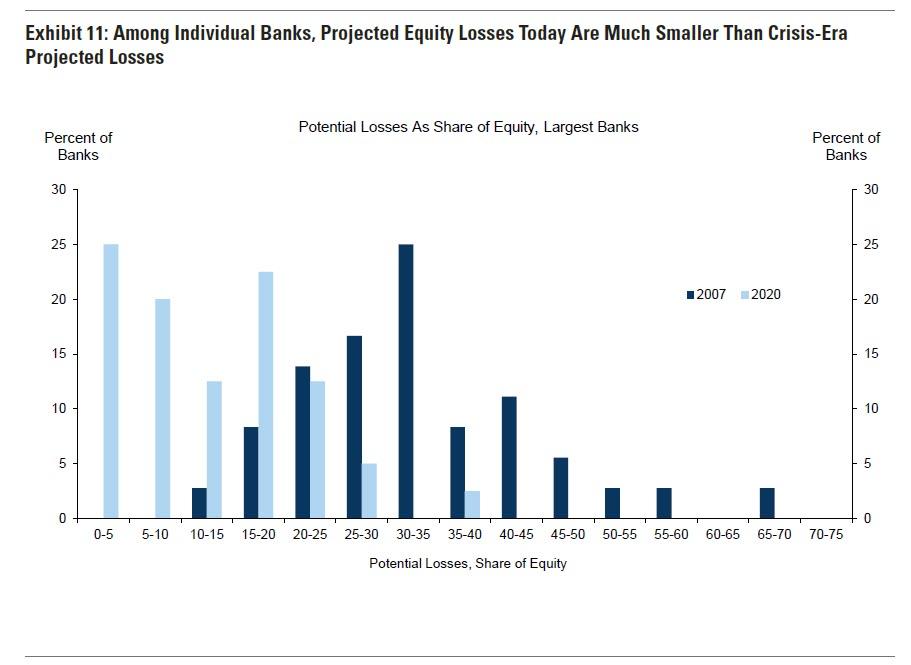

Finally, the bank looks at lending exposure of the largest banks individually: bank-level data can reveal differences across banks and highlight whether there are a significant number of banks with large exposures to at-risk categories. Naturally, using the optimistic assumptions profiled above, Goldman finds that while there is dispersion among the largest banks in their exposure to losses, almost all of the largest banks today are less vulnerable than the median large bank was prior to the financial crisis, thus invalidating the entire analysis for the simple reason that the current crisis may end up being far more dire to bank loans than 2008/2009 if an economic recovery isnt forthcoming in short notice.

In summary, Goldman finds that while financial stability concerns appear manageable, significant downside risks remain. A slower than expected recovery and a prolonged downturn would likely stress the banking system further, and a growing share of riskier lending is now done by less regulated nonbank financial institutions, where risks are harder to assess. Its conclusion: “Should a more adverse scenario arise, Fed officials have indicated the willingness to further help facilitate the provision of credit by the financial system.”

In other words, if the coming default crisis ends up being as bad as the GFC, the Fed will end up owning a whole lot more bankrupt bonds and loans than just Hertz.