This story was originally published by Real Clear Wire

By Mead Treadwell

Real Clear Wire

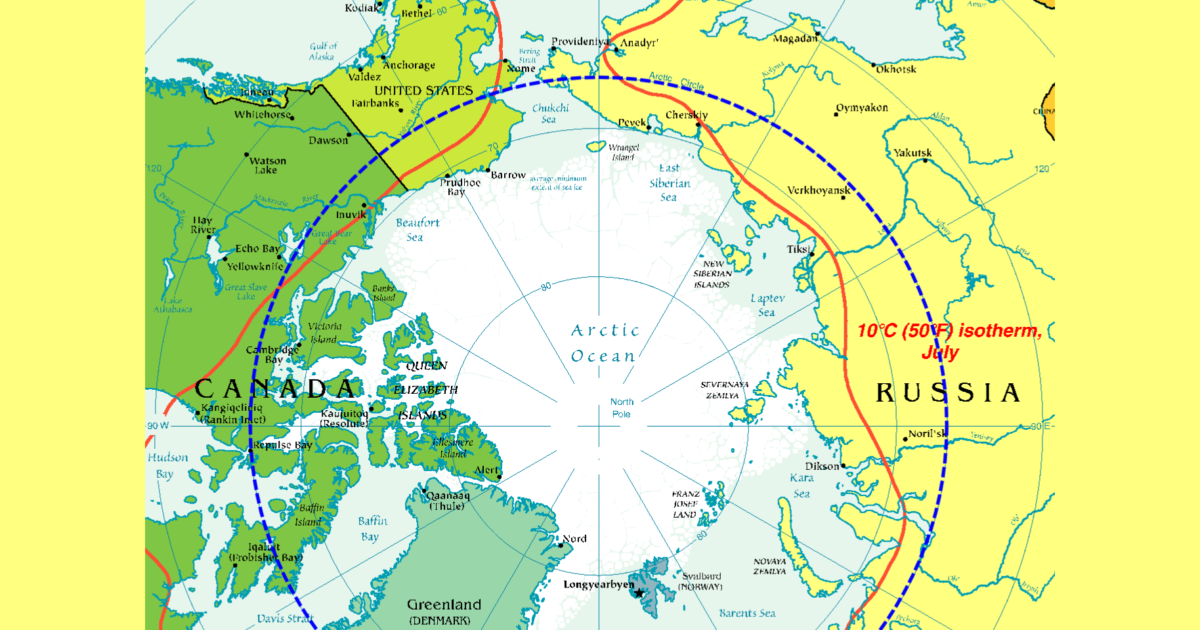

America’s attention to Arctic security has intensified in recent years. Our force structure has grown deliberately, a word that usually means “on purpose.” For this Alaskan, particularly when Russia and China practice war games with live ammunition in Alaska’s fishing grounds, “deliberate” can also mean “slowly,” or “not fast enough.”

More intensive U.S. security “deliberation” might best be directed now toward Antarctica and the Southern Ocean, too.

In geopolitics, the Antarctic has been quiet to date, or at least less competitive. A great circle air route over the South Pole has less traffic, and southern shipping has less strategic significance to world markets or military logistics. The Antarctic treaty system bans military activity and mineral exploitation on the Southern Continent. Environmental and science cooperation has been stronger at times in the South than in the North polar region.

But great power competition knows no bounds. Russia abandoned international law by invading Ukraine. China, an ally of Russia, has refused to renounce violence in its goal of “reunification” with Taiwan. Both nations have put trust in treaties – and trade deals – at serious risk. Reminiscent of the Cold War, we must wake again to counter superpower “positioning” in far reaching places, from the Moon to the Antarctic.

Now, experts such as General Chuck Jacoby – who earned his Arctic credentials as chief of U.S. Army Alaska, NORAD and the U.S. Northern Command – are warning that the power struggles playing out in the Arctic today could be a preview of what is to come in Antarctica. The time has clearly come to view polar security through an Antarctic lens as well.

To suggest the Antarctic could be a battle zone may sound a bit fantastic. The continent has been demilitarized for over 65 years by a treaty which has also put territorial grabs off limits. But in a 2021 joint essay with the Air Force Academy’s Ryan Burke that was published by West Point’s Modern War Institute, the two caution that “Antarctica faces many of the same realities (and capability gaps) as the Arctic, only delayed by ten to fifteen years” and that “well-intended international agreements rarely stand up against the realities of evolving technology, interests and opportunity.”

Some observers believe that China and Russia may be counting on the Antarctic Treaty System to fall apart or even actively working towards its demise. Apparent collaboration by the two countries to block new conservation areas under the Treaty may help set up a 2048 repeal of its ban on mining and energy production. That could set off global competition for natural resources in and around the continent.

Chinese concerns are often voiced about America’s growing alliance with Australia. Down under, China’s recent construction in Antarctica has caused fear that a dual use spying facility on now exists on Antarctica with potential threats to the security of America and its allies.

Against the backdrop of these challenges, the United States has, unfortunately, been reducing its Antarctic presence. The National Science Foundation (NSF) has had to curtail its Antarctic research programs, with over half of the 131 projects and activities funded for 2023-24 austral summer cancelled due to budget, housing, and logistical problems. We should support robust polar research programs at both ends of the world.

Some U.S. security footwork happening now in the Arctic could pay off in the Antarctic. New U.S. Coast Guard Polar Class heavy icebreakers on order will work both North and South. Army Paratroopers from Alaska who train making winter jumps far above the Arctic Circle also run joint maneuvers with our southern allies, like Australia and Chile. To counter Arctic cold, dark and distance, DoD has hired more ice pilots for Navy Arctic-capable submarines (not all U.S. subs can surface through the ice). An Army Cold Regions Test Center near Delta Junction, Alaska helps military procurers ensure that equipment and weapons work well in extreme cold. DoD’s Ted Stevens Arctic Security Studies Center, and Homeland Security’s Arctic Domain Awareness Center (ADAC), are helping the U.S. fill response gaps with useful innovations for security at both ends of the earth.

There’s more to be done. Antarctica is barely mentioned, if at all, in our services’ strategic plans. While military aircraft and Coast Guard icebreakers support U.S. logistics for Antarctic research now, it doesn’t hurt to build DoD familiarity in the region with more support, too.

When it comes to Arctic security, I try never to cry wolf. But missile technology is changing, and once fringes of the world now shape the defense realities of the world. For too long we have been playing catch up in the Arctic. Defense preparation for the Southern Ocean, compliant with Antarctic treaties, will help us deter war – and maintain surer footing in both polar regions.

Mead Treadwell served as Lt. Governor of Alaska 2010-2014, and a Commissioner of the U.S. Arctic Research Commission, 2001-2010, Chair under Presidents G.W. Bush and Barack Obama, 2006-2010, during the last International Polar Year which brought greater science cooperation to both the Arctic and Antarctic.

The post Antarctic and Arctic Security Threats Are Converging appeared first on The Gateway Pundit.