Covid-19 Cargo Cults & Why The Market Is Still Too Complacent

Authored by Rusty Guinn via EpsilonTheory.com,

In the South Seas there is a Cargo Cult of people. During the war they saw airplanes land with lots of good materials, and they want the same thing to happen now. So they’ve arranged to make things like runways, to put fires along the sides of the runways, to make a wooden hut for a man to sit in, with two wooden pieces on his head like headphones and bars of bamboo sticking out like antennas—he’s the controller—and they wait for the airplanes to land. They’re doing everything right. The form is perfect. It looks exactly the way it looked before. But it doesn’t work. No airplanes land. So I call these things Cargo Cult Science, because they follow all the apparent precepts and forms of scientific investigation, but they’re missing something essential, because the planes don’t land.

Richard Feynman, The Cargo Cult Science (Speech at Caltech in 1974)

I tease Ben sometimes for devoting his graduate studies to political science. Not because it isn’t a worthy field of study. I tease him because the idea of politics being a science is absurd on its face. And then he usually reminds me that my economics degree is nominally referred to as a science degree, too.

I am immediately chastened.

There are a lot of scientifically minded people in the investment industry. In general, this is for the good. I mean, of course it is. Investing in risky assets constantly appeals to our baser tendencies toward fear and greed. Worse, we do not respond to those appeals in isolation. We are surrounded by others who are watching us and responding to our actions for their own benefit. Process is a gift to investors.

And yet.

When we are free to be, shall we say, uncommercial, outside of the behavioral benefits accruing to process-adherence it is very difficult to find much that we do in the investment industry that is not what Physicist Richard Feynman called cargo cult science. When he wrote and spoke about cargo cults, he usually referred to very obvious pseudosciences like phrenology, astrology or reflexology. But his fundamental analogy is much more expansive, and in classic Feynman style, works in micro, macro AND meta. It is simultaneously an illustration of the practice of pseudoscience and the philosophy underlying pseudo-scientific practice.

If you imagine the islanders trying to recreate the landing of the airplane that brought goods and supplies, you are seeing the frustration yielded in the practice of pseudoscience. They observed a pattern: runway is cleared, fires are lit, man sits in a shack with things on its head, plane with goods and supplies lands. Easy peasy. They want to reproduce the final result, so, they get to clearing and manufacturing a makeshift set of wooden headphones.

It sure looked better in the backtest.

But Feynman’s analogy is not just an illustration of what cargo cults do. It’s also an illustration of why they do it. Instead of thinking about the airplane as an illustration of some feature of the world a scientist might be trying to research, think about the airplane as science itself. People who earnestly want to be more scientific see what scientists do. They do experiments. They measure data. They write it down. They perform calculations based on the data their experiments yielded. They build things based on those experiments. Alas, adhering to the cartoon of sciencey-looking process is not science. Neither is the closely-related meme of Yay, Science!

I don’t mean to be unkind. I’m also not condemning inductive reasoning in full, since in sciences where it can be combined with observation in ways that aren’t available to us in financial markets it has been responsible for some of our great discoveries.

But if your adviser or consultant does a lot of slicing and dicing of quintiles and quartiles on some good-sounding fundamental dimension and showing you the returns over the last 20 years if you’d bought this one and sold that one, you’re probably paying a cargo cultist to clear you a runway. Many quantitative managers do a lot better than this, of course. Some are, I think, doing something that is close enough to science to warrant the name. But even then, the airplane landing is dependent on some actual transmission mechanism to make it land. And the actual transmission mechanism in markets after removing abstraction layers is always – ALWAYS – another human making a decision for whatever reason they make decisions. This thwarts a lot of good theories. Ours included.

The right question to ask, both in science and in the maybe-science variant we perform in financial markets, is always this:

Why do you believe the measurements you are producing and the actions you are taking based on those measurements are related to the actual mechanic in the real world which produces the thing being measured?

It’s the right question if you’re thinking about what Covid-19 means for your portfolio, too.

The biggest concern I have as a risk manager is related to this question. It isn’t that I am concerned (as an investor) about how many people are infected with Covid-19 in the United States today. It isn’t even that I don’t know how many people are infected.

It’s that it isn’t knowable.

It isn’t knowable because we completely botched testing on initial suspected cases, and we have continued to permit that error to compound. To be clear, I don’t mean “unknowable” in the sense that we will always be inexact in our predictions. I mean unknowable in the sense of uncertainty: that you could produce a dozen different estimates of where we are at today in the development of Covid-19, and any attempt to assign probabilities to each of those estimates would be no better than an arbitrary guess. If your epistemic uncertainty about the predictive power of any of your models is not keeping you up at night, I think you’re making a mistake.

I think that has two implications for investors and asset owners.

The first is that we must be extremely cautious of anyone peddling quantitative, predictive or scenario analysis of what this means for your portfolios. Anyone who is acting positively on the belief that they know something is a cargo cultist. Anyone showing you charts of prior contagions and pandemics and showed you what happened next – whether they intend to frighten you or calm you – is a cargo cultist. Ignore it. And for God’s sake, don’t act on it.

Not until measurement has meaning again.

The second is somewhat related to the first. Acting positively because you think you know something is not the same as responding to the fact that you don’t. Every position in our portfolio is an implicit bet on a variety of things. Your active security positions – overweights and underweights – are bets that other investors will recognize or change how much they care about certain traits that exist today or that you are predicting will exist in the future. How confident are you that the kind of bets you are making will not be swamped by bets and responses other investors will inevitably make about Covid-19?

Your exposure to risky assets in general represents an implicit bet, too.

It’s a bet on functioning economies and trade. It’s a bet on available credit and liquidity. It’s a bet on productivity and the way capital marshals that into equity value. And, uh, I’d be going a bit off-brand if I didn’t mention that it’s a bet on a friendly and accommodative institutional apparatus that includes both central banks and the cadre of MMTers who occupy both political parties. Most importantly, it’s a bet that investors still care about those things. I still think they’re good bets in the long run. I actually still think they’re good bets in the short run, by which I mean that if your central case is that the world will largely continue to spin in 2020, history tells us that you are more likely than not to be correct.

But distributions get a bit funny in the face of the unknowable, folks. While the chest-pounding prediction game practiced by the media, banks and asset managers coerced by their head of sales to go on CNBC IS about acting on what’s more likely than not to be true, investing is not.

In short, if your confidence that the models leading you to active positions will matter in the near term is high, or if your confidence that the aforementioned uncertainty is already being discounted is high, we think you are wrong.

Part of the reason is epistemological. Uncertainty alone may be enough. But that isn’t all. We’re concerned about where we are on the Covid-19 narrative, too.

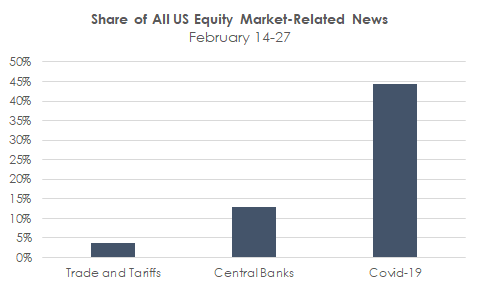

Our analysis of narrative structure shows that Covid-19 is dominating the last two weeks of markets coverage in a way that no topic has since we begin tracking macronarratives. Here’s the activity in traditional media:

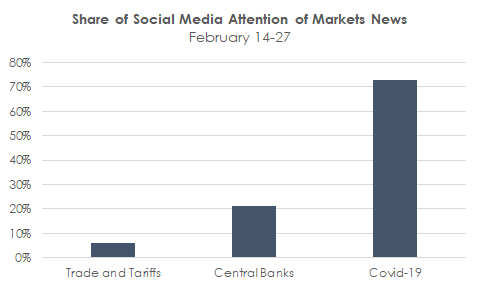

And here’s the activity in social media.

But here’s the thing: our attention measure for Covid-19 over the same period is LOWER than each of Trade War AND Central Banks. It’s lower than the AVERAGE of all financial markets news.

What does that mean?

It means that authors reference the Fed when they’re talking about banks, when they’re talking about consumer borrowing activities and mortgages, when they’re talking about fears of Covid-19 and other market risks, when they’re jawboning for more easing, and when they’re talking about President Trump. It means that authors reference the Trade War when they talk about Boeing, and Tesla, and farmers, and consumer prices, and Trump’s reelection, and factory shutdowns, and supply chains.

But Covid-19 news? Right now, it’s mostly just about Covid-19 and the initial investor response. There’s a smattering of supply chain linkages, and a couple of companies reporting and warning about its impacts. But generally speaking, we haven’t yet seen the deluge of linking-everything-to-Covid-19 that we expect is coming. Even at a high volume of coverage, it’s its own beat. A sideshow.

As of February 27, even after a 10% drawdown, we believe the narrative about Covid-19 is complacent.

What would we be doing if we were an asset owner or adviser? Most importantly, we’d be ignoring the cargo cultists. We’d avoid actions predicated on predictions, and respond instead to the fact that we don’t know. What does that mean?

-

It means we’d be actively trimming the risks of ruin. That means leverage, concentration and illiquidity. The last one’s definitionally tougher to trim, so focus would be on the first two.

-

It means we’d put off hiring new active managers in search of idiosyncratic alpha, and we’d avoid paying for existing active strategy exposure if frictional costs were low (e.g. anything on swap, accessed through platforms like DB Direct, etc.)

-

It means we’d be thinking long and hard about our dependence on backward-looking covariance estimates. If I was a steward for investors with a short investment horizon or a low risk tolerance that was based on some conversation I had with them about a remote probability of a major loss, I’d be inclined to pull back exposure to risk assets.

-

It means we’d be couching our investment committee conversations for the near future in terms of insurance. In short, are you an institution whose objectives are better served by paying a 10% premium on your equity book by locking in this drawdown and avoiding potential tails? Or does your agency structure, investment policy and institutional temperament permit you to self-insure and avoid the uncertainty of foregone gains from the brutal difficulty of timing re-entry?

-

It means we’d be doing all of the above until the cargo cult of Covid-19 analysis turns back into science. In short, we’d be doing the above until we felt that the measurements being provided about the state of Covid-19 infections reflected some underlying reality.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 02/27/2020 – 15:45